Sunday

Two Predictions about the Distribution of Life in the Universe

There is a rule in software development called the zero one infinity rule, or ZOI, originally formulated by Willem van der Poel, according to which a process should be completely disallowed, or allowed only once, or no limit should be placed on the number of times it occurs. This is a rule of thumb for programming, but it also can be interpreted in a much wider sense. Robert Hazen, despite being the careful scientist that he is, gives a metaphysical spin to the zero one infinity rule:

“In short, ‘zero, one, many’ means either that a natural phenomenon never happens (time running backward, for example), or it happens exactly once (a ‘singularity’ like the Big Bang), or it has happened more times than we can count (perhaps the origin of life).” (Robert Hazen, Symphony in C: Carbon and the Evolution of (Almost) Everything, p. 199)

In the context of the zero one infinity rule, we know that the appearance of life in the universe does not exemplify zero, so either life in our universe is one or many. Taking each the horns of this dilemma in turn, if life on Earth is unique, there is nothing more to say about the distribution of life in the universe: it has a distribution of one, limited to Earth. Any interesting prediction regarding the distribution of life in the universe will either be a prediction of whether our universe exemplifies one or many, or it would be a prediction regarding the distribution of the many instances of life in the universe. My prediction will be concerned with the latter, not the former; I am not going to predict how much life there is in the universe, or the frequency of its appearance in space or time.

If we were to establish that life is unique and distinctive to Earth, there would be as little to say as there would be to say of a universe with zero life, so we begin with the hypothesis that life is sufficiently common in the universe that there are enough instances of independent origins of life events that statistically valid generalizations can be made regarding its distribution. I adopt this hypothesis not because I believe it to be true (at present I have no reason to prefer the hypothesis of the uniqueness of terrestrial life or the prevalence of life in the universe), but only because it is a useful point of departure for thinking about life in the universe.

Supposing, then, that there are many worlds with life, and further supposing that life on these many worlds independently originated (or, at least, mostly independently originated, meaning that panspermia plays little or no role in the large-scale distribution of life in the cosmos, but more on panspermia below), my prediction on these assumptions concerns the distribution of mechanisms by which life arises in this scenario of life being prevalent in the universe.

Suppose further that we make a complete survey of the possible biochemical pathways to life, of which there are many already, and, we can infer, there will be more as origins of life research continues to develop. Again, I cite Robert Hazen, who gave a comic twist to the number of origins of life scenarios that contend for researcher’s attention:

“A popular game in origins-of-life research is to dream up an ‘origins scenario’—an elaborate, sweeping, often untestable story of chemical and physical circumstances by which the living world emerged from a lifeless geochemical milieu.” (Op. cit.)

Given many possible origins of life biochemical pathways, and many worlds with biospheres, it would be reasonable to assume that different biochemical pathways are responsible for the origins of life on different worlds. This is a reasonable assumption, but not a necessary assumption. We do not yet know how tightly constrained life is, but if life is tightly constrained, there may be only a single biochemical pathway to a single kind of life. If this is the case, I predict, on this basis, that life on Earth will be shown to be distinct. (This is yet another prediction, distinct from the two predictions made below, thus not included in the two predictions noted in the subtitle above.) However, there could be a single biochemical pathway to life that is represented on multiple planets throughout the universe.

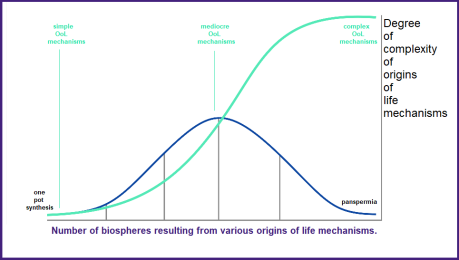

If life is not tightly constrained, that is to say, if life is loosely constrained, or unconstrained and prolific in the universe, then many biochemical pathways to life will be represented on many different worlds. What kind of distribution of origins of life mechanisms would we expect to see under these circumstances? My two predictions for this distribution are based on two familiar ideas: the bell curve and the Pareto principle:

1. Origins of Life Bell Curve: I predict of the many biochemical pathways to life, that the bump in the bell curve will be filled with the most common mechanisms for the origins of life, representing some degree of mediocrity of the complexity of the process; the left of the bell curve will be sparsely populated by the simplest possible mechanisms, while the right of the bell curve will be sparsely populated by the most complex mechanisms for the origins of life.

2. Origins of Life Pareto Principle: I further predict that about 20 percent of the biochemical pathways to life will account for about 80 percent of instances of planets with biospheres, making these 20 percent of mechanisms literally the vital few, i.e., those mechanisms most responsible for life’s prevalence in the universe.

I furthermore predict that terrestrial life will exemplify the principle of mediocrity, such that the mechanisms responsible for origins of life on Earth will fall close to the center of the bell curve, and these mechanisms will represent those 20 percent of such mechanisms responsible for 80 percent of life in the universe. In other words, life on Earth is in the 80 percent, and therefore typical of life in the universe.

There is much more that could be done to clarify the above predictions, and as further origins of life biochemical pathways are identified and refined, it will become increasingly possible to compare and contrast these mechanisms, and eventually to quantify the degree of complexity of each. The degree of complexity of a biochemical pathway to life is itself an idea in need of clarification. What are the dimensions of complexity of origins of life biochemical pathways? These may include the number of steps necessary to pass from inert chemical reactions to biochemistry, the specific mineralogical prerequisites for biochemistry (and how many steps are necessary for these precursors to evolve), the number and diversity of chemical processes that are required, the amount of time necessary for these processes to converge upon life, and so on.

In the illustration above I have identified the most complex origins of life pathway to be panspermia, but this is ambiguous. However, my reason for doing so is that any origins of life on a planet (or other celestial body, such as a moon) in which panspermia is the mechanism necessarily involves some other origins of life biochemical pathway plus the extra step of a panspermatological vector. It could be argued that a simple biochemical pathway plus panspermatological distribution is likely to be simpler than the most complex biochemical pathways that do not involve panspermia (i.e., all steps of which occur on a single planetary body). This could be factored into a more adequate and refined quantification of the complexity of biochemical pathways to the origins of life.

Needless to say, I will not live to see my predictions either confirmed or disconfirmed. Any survey of life in the universe, even a superficial and perfunctory survey, would require cosmological scales of time to investigate a cosmos filled with potentially inhabited worlds. Also, the effort to confirm or disconfirm such predictions is predicated upon a scientific effort that would also have to be cosmological in scale, and even if life is prevalent in the universe, there is no assurance that intelligent agents descended from any biosphere would take up this task at the requisite scale.

There is a slight possibility that our solar system is filled with microbial life in all manner of unlikely niches, and, if this is the case, and if we were to discover our solar system not only to be rich in life, but also that this life was the result of independent origins, then we could extrapolate from life in our solar system to the mechanisms of the origins of life represented in the wider universe. In this case, our solar system would be a cosmological Petri dish, and it might well be possible that I could see the first results of exploration of our solar system, whether through sample return missions or through boots-on-the-ground research. I make these predictions, then, not with an eye toward being proved right or wrong, but out of disinterested curiosity in what we might call stochastic metaphysics—that is to say, how frequency distributions ought to predict the ultimate constitution of the natural world. Thus naturalistic metaphysics can be speculative as well as descriptive.

In the event that life from multiple origins events is to be found throughout our solar system, the extrapolation of the distribution of its origins of life mechanisms to the wider universe itself would constitute a further prediction: that the distribution of origins of life mechanisms in the small (in our solar system) will be mirrored by origins of life mechanisms in the large (in the universe). I hesitate to endorse this prediction, as the chemical compositions of other planetary systems derived from other proto-planetary discs, and these proto-planetary discs in turn derived from distinct precursor events (viz. the particular chemical composition of supernova events in the stellar neighborhood that would enrich proto-planetary discs with their elements), will be sufficiently distinct from the chemical composition of our solar system that the different abundances of elements and isotopes will likely beget different chemistries.

To recap: I said I would make two predictions about the distribution of life in the universe, but I actually made four predictions: (1) if life is tightly constrained, Earth will be the only living world, (2) the origins of life bell curve, (3) the origins of life Pareto principle, and (4) life on Earth will exemplify the principle of mediocrity based on the distribution of life predicted above. I also suggested a fifth prediction that could be made, but I hedged on that one.

. . . . .

. . . . .

. . . . .

. . . . .

. . . . .

. . . . .

. . . . .

. . . . .

Institutional Purpose

13 May 2021

Thursday

Taking Prisons and Schools as Case Studies

If we think of institutions at all, we usually assume that they were created to serve a particular purpose, even if they are flawed in fulfilling this purpose. Carroll Quigley postulated the social process of the “institutionalization of the instrument,” according to which institutions are created as instruments to attain a particular end, but these instruments are then transformed into self-serving institutions that are increasingly poor instruments because their purpose shifts from fulfilling its instrumental purpose to fulfilling a self-defined institutional role. I do not disagree with this—Quigley made an important observation—but it isn’t the whole story.

Small institutions can retain a sense of purpose that remains focused and true to the intent of the founders (though small institutions do not invariably retain their purposes intact), but large institutions, or institutions that grow large over time (often as a result of their success as an institution (which could be understood as a refutation of the institutionalization of the instrument, or which could be understood as the success of the institution at the expense of its functionality as an instrument), usually cannot maintain a tight focus on a purpose. As larger numbers of persons participate in an institution, and in doing so bring with them their particular ideologies and biases, institutions sometimes shift their focus, or acquire multiple purposes, some of which are at odds with each other.

A particularly clear example of this is the function of prisons in a large nation-state. Prison systems can be large institutions, employing thousands of persons, and housing millions of inmates, over an extensive and diverse geographical region. A little reading about prisons will make it clear that there is no consensus as to the function of a prison, but there are at least three paradigmatic functions, each entertained by a distinct interest group, and these three purposes are separation, reform, and punishment.

The efficacy of the prison system is reduced by its failure to coalesce around a single purpose; prison is clearly a separation from wider society, but it is not clearly punishment and it is not clearly reform. Some prisons tend more toward punishment, some toward reform, and no doubt there are institutions that try to tread the neutral line of merely separating the prison population from wider society without punishing or reforming inmates. Moreover, it would be entirely consistent to maintain all three purposes at the same time, e.g., if one holds that miscreants must be separated from society so that they may first be punished and later reformed.

While the situation with schools is similar, the entirety of the educational establishment is even larger than the prison establishment, and so the purposes of schools are even more diffuse and difficult to pin down than the purposes of prisons. Ideally, we can summarize in a single word that the purpose of school is education. But what is education?

A little reflection on educational institutions possibly reveals another tripartite division of educational purposes (like the tripartite division of the purposes of prisons), though, again, the situation of schools is less clear than that of prison. The whole problem is wrapped in layers of history and ambiguity that make it difficult to discern the fundamental conception of education implicated in any one school system or any one curriculum at any one time. Despite these ambiguities, we can, in any case, discern idealistic, pragmatic, and traditional purposes in our educational institutions.

The idealistic conception of education is that it is concerned to inspire children to attain their highest potential, to bring out their creativity, and not merely to allow them to express themselves, but actually to facilitate their self-expression, to advance this self-expression and to celebrate it. This idealistic conception of education is usually found alongside the mantra of teaching children how to think, and not what to think. The point here is to develop and event to improve the child’s mind so that child can go on to achieve great things in life.

The pragmatic conception of education can be expressed pragmatically or cynically. Pragmatically, it is about educating children in skills that they will need in the workforce, enabling them to obtain gainful employment and thus to stand on their own two feet. The cynical expression of the pragmatic conception is that the purpose of education is to produce useful drones for society who will work hard, not question their betters, and accept their lot in life meekly. In this conception, the school system also serves as a de facto babysitter as a place for parents to dump their children while they are at work fulfilling their own purpose as useful drones. Thus school “prepares” children for the workforce, not by improving their minds, but by providing them with an analog of adult society: while their parents to go work each day, they go to school each day, drumming into their young minds the lessons of unalterable and unimaginative routine.

The traditional conception of education is to impose the “primary mask” upon young people, that is to say, to force them into conformity with the standards and norms and values of the society into which they are born. Education shapes individuals, and the traditional conception of education seeks to shape them into upstanding citizens who can fulfill their role in society. This conception of education also has its inspiring component, in so far as education is understood as passing along the legacy of a culture to its youngest members, so that they can, in their turn, transmit this legacy to their children. This was powerfully expressed by Matthew Arnold in the 19th century:

“…culture being a pursuit of our total perfection by means of getting to know, on all the matters which most concern us, the best which has been thought and said in the world, and, through this knowledge, turning a stream of fresh and free thought upon our stock notions and habits, which we now follow staunchly but mechanically, vainly imagining that there is a virtue in following them staunchly which makes up for the mischief of following them mechanically.”

This conception of the best that has been thought and said in the world thus contains within it a criticism of the pragmatic conception of following mechanically our stock notions and habits, and this is the sense in which the traditional conception, despite its profound conservatism, also involves an inspiring element. In order for a child to eventually pass along the cultural legacy that is made available to them, they must master and understand that legacy, or they are merely parroting back what has been said to them.

While each of these conceptions of the purpose of education can be found in isolation—in its pure form, as it were—we are more likely to find some admixture, and probably there are even those who combine all of these conceptions of education into one vision: inspiring young minds, preparing them for the world, and conveying to them the legacy of tradition.

In the American tradition of the one-room schoolhouse, in which multiple age cohorts were educated side-by-side, we can most readily see the traditional and the pragmatic functions of education in action. This was always an institution that was jealous of retaining local control, and was directly responsible to parents in the area whose children attended the school. These parents would be eager for their children to be acculturated into their tradition as well as preparing them for their roles in society. However, the idealism of teaching and education was always present, on the part of the teachers if for no one else, and this vision could be said to have triumphed insofar as it is the “official” purpose of education, however far actual education departs from this ideal.

As the US school system has grown to gargantuan dimensions, all of the features of traditional American education have been lost. Curricula are adopted on a national level, parents often have no idea what their children are being taught in school, local school boards no longer have the power they once wielded, and the schools and the educational responsibilities now resemble a highly-specialized industrial facility in which children are broken down into single age cohorts, and different specialized subjects are taught in different areas of a rambling building usually covering several acres—with children’s lessons almost perfecting mimicking the division of labor that their parents experience in their employment. Thus while the idealistic doctrine has triumphed in the vision of professional educators, the actual practice of education today most closely resembles the pragmatic conception.

In this dystopian reality of contemporary educational institutions, not only has the instrument of education been institutionalized, but the tightly-focused purposes of small schools have been replaced by slogans, ambiguity, and diffuse efforts that point in no one particular direction. As with prisons, schools are less effective as a consequence of having many different purposes, some at odds with each other, driving competing educational agendas. Just as there are fundamentally different conceptions of what a prison is, what it is for, and what its role in society is, so too there are fundamentally different conceptions of what a school is, what education is for, and what the role of education ought to be in society.

What is true of prisons and schools is also true for other large institutions, especially for the largest of the institutions that human beings have created—civilizations. Civilizations are informal institutions in contradistinction to the formal institutions of prisons and schools, but all institutions are of the same genus, whether formal or informal.

I often say of civilizations that it is difficult to discern their purposes (which I call the central project of a civilization), and it is especially difficult to discern the purpose of our own civilization, partly because we cannot see clearly something so close to us—we look upon our own civilization from the inside out, as it were—and partly because we cannot be objective and impartial about something that constitutes our identity. I also sometimes define a civilization as an institution of institutions, i.e., civilization is an institution comprised of a multitude of subsidiary institutions. Given that these subsidiary institutions are often large institutions like prisons and schools, which themselves cannot be clear about their purposes, it holds a fortiori for civilization, the sum total of a multitude of institutions, that it cannot be clear about its purposes.

It would probably be true to say that individuals within a given civilization may hold fundamentally different conceptions of their civilization of which they are a part. Moreover, it is likely that, because of this failure of reflexive self-understanding of civilization, our interpretations of other civilizations—both past civilizations and other civilizations today, as well as future civilizations distinct from our own—are probably faulty. That is to say, we probably project purposes upon other civilizations that do not reflect the actual purposes of these civilizations.

If we are to understand civilization to any extent, we must have recourse to the scientific use of the appearance/reality distinction, recognizing that civilizations may have a certain appearance of purpose, whereas their true purpose may be difficult to discern, hidden as it is behind the veil of appearances.

. . . . .

. . . . .

. . . . .

. . . . .

. . . . .

. . . . .

. . . . .

. . . . .

Science as an Institution and as an Ideal

13 April 2021

Tuesday

Science as an institution today consists of colleges and universities, which are in part funded by government money that is parceled out in the form of grants and loans, decided upon by numerous committees (themselves institutions), which money is often funneled through additional committees once it arrives at a given institution. (It is well known among academics that one must attempt to get a grant twice the size that one needs, since the institution is going to take half of it.) Individual laboratories are also institutions within institutions, whether they are within the government, within a university, or within private industry.

There are numerous scientific societies, many of them distinguished by long histories and eminent alumni, which are formally organized as institutions for the advancement of science and also to assist individual scientists in the pursuit of research goals as well as career advancement. There are student associations with disciplinary specializations, which advocate for early career researchers.

There are also publishers of journals and books (often purchased by university libraries) who accept manuscripts from individuals frequently employed in institutions of higher education, and which when published are frequently read by both students and instructors at institutions of higher education. Students attend these institutions and read these materials in order to obtain a credential provided by these institutions, which gives them an institutional stamp of approval, and some of them will go on to themselves become instructors in this system of higher education.

A battery of subsidiary institutions support and facilitate these primary scientific institutions, and the whole system ripples out through the economy like Adam Smith’s famous example of a day laborer’s woollen coat (I quote this passage in The Technology of Living). The many and various institutions of science as an institution thus cannot be cleanly separated from wider society, as any attempt to isolate them would involve a sorites paradox: where do we draw the line between economic, social, and cultural activities that are scientific and those that are not?

Science as an ideal has no institutions to support it; science as an ideal exists only in the minds of a number of individuals to aspire to scientific inquiry and the growth of scientific knowledge. The scientific ideal serves as a norm against which individuals and even some institutions measure their progress in scientific inquiry and the growth of scientific knowledge. This ideal is not about the particular details of the discipline to which any given scientist may contribute, but rather it addresses a broader vision of the conduct of an ideal life in science, or even an ideal scientific institution, which puts scientific truth before any other consideration, and never fears to speak out on behalf of impartial and objective inquiry.

While science as an institution nominally supports science as an ideal, we all know that science as an ideal often finds itself in conflict with science as an institution. Institutions inevitably come to be dominated by individuals and their personalities, or by cliques of individuals. Ultimately, cliques in control of scientific institutions do far more damage to the scientific ideal than even the most boorish personalities. Individuals eventually die, allowing science to progress one funeral at a time; cliques can impose a stranglehold upon an institution for generations, and often do.

Must science be institutionalized and thus subject to these human, all-too-human frailties and pettiness? It may well be inevitable that science becomes institutionalized, and not only institutionalized, but institutionalized at the largest scale as “big science,” which increasingly plays a prominent role in contemporary scientific knowledge. In many disciplines all the low-hanging fruit of scientific knowledge has been plucked, so that the further growth of scientific knowledge requires coordinated effort over periods of time that can be measured in the overlapping careers of multiple scientists, and this means that “big science” becomes increasingly unavoidable as scientific knowledge advances.

Big science is a kind of informal institution; most involved in big science understand intuitively how it works, i.e., that they are involving themselves with a scientific research program that requires the resources of government, industry, and educational institutions working together over a period of time that is likely to exceed the entire length of an individual’s career as a scientist. A major scientific instrument constructed within the paradigm of big science will almost certainly have a formal institutional structure—think of the LHC, for example—but such big science institutions exist within a larger informal institution—in the case of the LHC, this larger informal institution is the coordinated effort of many teams of scientists at many particle accelerators to elaborate the Standard Model, whether through refining and extending it, or through finding some inadequacy in it, and thus setting physics on a new path.

Even particular scientific research programs—say, to continue with the theme of particle physics, the research program into supersymmetry, or string theory—transcend most formal institutions, in the sense that they are expressed in a number of distinct institutional contexts, even as they find their place within the even larger informal institution of particle physics and big science. Scientific research programs are informal institutions greater than most formal institutions, but less comprehensive than big science, or science itself.

We can see, then, that big science is constituted by a network of formal and informal institutions that overlap and interact. These many institutions, both formal and informal, also overlap and interact with science as an ideal. For science as an ideal is also, like science as an institution, not one thing only, but many things—playing many roles in many different lives. Within the ideal of science there are ideals for science itself—the idealization of the scientific method, the final form of which is out of reach, but nevertheless can be more closely approximated with each scientific effort—as well as ideals for individuals practicing science, and ideals for scientific institutions.

It is possible that some of the ideas of ideal science are more applicable in one life than in another, and more applicable in one institution than in another. One scientist may see himself as a living embodiment of the scientific method, another as a personal exemplification of the ideal scientist, and a third as a loyal and dedicated member of a scientific institution (a true believer in institutions, as I described years ago in A Third Temperament). Thus the multiplicity of scientific ideals is interwoven with the multiplicity of scientific institutions. And, just as there are formal and informal scientific institutions, there are formal and informal scientific ideals. The scientific method, to the extent that it is explicitly codified, is a formal ideal of science. The aspiration to pure scientific impartiality and objectivity is an informal ideal of science.

Formal institutions, needless to say, favor formal ideals; informal institutions grow out of an intuitive appreciation of informal ideals. An explicitly constituted institutions can codify the explicitly formulated codification of scientific method into its institutional imperatives, for example, by requiring all projects superintended by the institution to embody some particular concrete expression of the scientific method. The implicit ideals of informal scientific ideals cannot be adopted in any meaningful way by an institution, even if that institution authentically abides by the ideals of science.

In all of this there is something hopeful and something dispiriting. Not myself belonging to the third temperament, it is difficult for me to see institutions as anything other than a betrayal of the individual and of the ideals of the individual. All science, as I see it, ultimately grows from the root of the informal scientific ideal, which has moved individuals to greater effort, to greater achievement, to greater knowledge, and to greater rigor. The growth of institutional science and big science militates against this personal ideal. That is the dispiriting aspect. The encouraging aspect, on the other hand, is the knowledge that into every generation some individuals with the authentic scientific temperament are born, who respond naturally to scientific ideals. These individuals can and will further render the scientific ideal explicit, and the extent to which it can be rendered explicit, it can be adopted by institutions. Even if these institutions are corrupt, they will become irrelevant if they stagnate. In order not to stagnate, they must draw upon those who are authentically inspired by scientific ideals, who produce the explicit formulations of that ideal that can be adopted by institutions. So there is hope, after a fashion, even if there is also despair.

. . . . .

. . . . .

. . . . .

. . . . .

. . . . .

. . . . .

. . . . .

Measuring the Size of the World

28 November 2020

Saturday

A Scientific Research Program That Never Happened

Carl Sagan liked to characterize the Library of Alexandria as a kind of scientific research institution in classical antiquity:

“Here was a community of scholars, exploring physics, literature, medicine, astronomy, geography, philosophy, mathematics, biology, and engineering. Science and scholarship had come of age. Genius flourished there. The Alexandrian Library is where we humans first collected, seriously and systematically, the knowledge of the world.”

Carl Sagan, Cosmos, 1980, pp. 18-19

Clearly, before the scientific revolution there were many intimations of modern science, but these intimations of modern science, these examples we have of scientific knowledge prior to the scientific revolution, are isolated, and almost always the work of a single individual, like Archimedes or Eratosthenes. Thus Sagan used the example of the Library at Alexandria to suggest that there was, in classical antiquity, at least an intimation of a research institutions in which scholars worked in collaboration with each other. How accurate of a picture is this of science in antiquity?

The philosopher of science Imre Lakatos used the phrase “scientific research program” to refer to a number of scholars working jointly on a common set of problems in science. These scholars need not know each other, or work together in the same geographical location, but they do need to know each other’s work in order to respond to it, to question it, to elaborate upon it, and to thus contribute together to the growth of scientific knowledge, not as an isolated scientist producing an isolated result, but as a community of scholars with shared methods, shared assumptions, and shared research goals. Did any scientific research programs in this sense exist in classical antiquity? And was the Library at Alexandria a focal point for ancient scientific research programs?

If there were scientific research programs in antiquity, I am unaware of any evidence for this. No doubt at some humble scale shared scientific inquiry did take place in classical antiquity, but no surviving accounts of research undertaken in this way describe anything like this. In Athens, and later at Rome and Constantinople, the ancient philosophical schools did exactly this, investigating common research problems in a collegial atmosphere of shared research findings, and since there was, in classical antiquity, no distinction made between science and philosophy, we can assert with confidence that scientific research institutions (Plato’s Academy and Aristotle’s Lyceum) existed in antiquity, and scientific research programs existed in antiquity (Platonism, Aristotelianism, etc.), but even as we assert this we know that this was not science as we know it today.

When universities were founded in the Middle Ages, these universities inherited the tradition of philosophical inquiry that the ancient schools had once cultivated, and they added theology and logic to the curriculum. If there is any research program in a recognizable science that extends through western history all the way to its roots in classical antiquity, it is the research program in logic, which we can find in antiquity, in the Middle Ages, and in the modern period still today. But the Scholasticism that dominated medieval European universities was, again, nothing like the science we know today. Scholars did collaborate on a large, even a multi-generational research program, in Aristotelianism and Christian theology, and in the late Middle Ages this began to approximate natural science as we have known it since the scientific revolution, but when the scientific revolution began in earnest, it often began as a rejection of the universities and Scholasticism, and the great thinkers of the scientific revolution distanced themselves from the tradition in which they themselves were educated.

One could even say that Galileo worked essentially in isolation, when, during the final years of his life, living under house arrest due to the findings of the Inquisition, he pursued his research into the laws of motion in his own home, building his own experimental apparatus, writing up his own results, and being segregated from wider society by his sentence. What is different in the case of Galileo however, what places Galileo in the context of the scientific revolution, rather than being simply another isolated scholar like Archimedes or Eratosthenes, perhaps with a small circle of intimates with whom they shared their research, is that Galileo’s work was shortly thereafter taken up by many different individuals, some of them working in near isolation like Galileo, while others worked in community (in some cases, in literal religious communities).

Alexander Koyré’s 1952 lecture “An Experiment in Measurement” (collected in Metaphysics and Measurement), details how Filippo Salviati, Marin Mersenne, and Giovanni Battista Riccioli all took up and built upon Galileo’s work. Some of the experiments undertaken by Mersenne and Riccioli demanded an almost heroic commitment to the attempt to make precision observations despite the technical limitations of their experimental apparatus. Riccioli built several pendulums and, with the aid of nine Jesuit assistants, counted every swing of a pendulum over a period of twenty-four hours. The many individuals who were inspired by Galileo to replicate his results, or to try to prove that they could not be replicated, is what made the scientific revolution different from scientific knowledge in earlier history, and this community of scientists working on a common problem is more-or-less what Lakatos meant by a scientific research program.

Since the scientific revolution we have any number of examples of the work of a gifted individual being the inspiration for others to build upon that original work, as in the case of Carl von Linné (better known today as Linnaeus), whose followers were called the Apostles of Linnaeus, and who spread out across the world collecting and classifying botanical specimens according to the binomial nomenclature of Linnaeus. During Linnaeus lifetime, another truly remarkable scientific research program was the French Geodesic Mission, which sent teams to Lapland and Ecuador in order to measure the circumference of the Earth around the equator and around the poles, to see which distance was slightly longer than the other.

While there were, in classical antiquity, curious individuals who traveled widely and who attempted to gather empirical data from many different locations, there was no community of scholars, inside or outside any institution, that, prior to the scientific revolution, engaged in this kind of research. We can imagine, as an historical counter-factual, if other scholars in antiquity had been sufficiently interested in Eratosthenes’ estimate of the size of the Earth that they had sought to replicate Eratosthenes’ work with the same passion and dedication to detail that we saw in the work of Mersenne and Riccioli. Imagine if the Library at Alexandria had conducted Eratosthenes’ experiment not only in Alexandria and Syene, but also had sent teams to the furthest reaches of the ancient world — the great cities of Asia, Europe, and North Africa — and had repeated their investigations with increasing precision with each generation of experiments.

If Eratosthenes’ determination of the circumference of Earth had been the object of such a scientific research program in classical antiquity, there would have been no need of the French Geodesic Mission two thousand years later, as these results would already have been known. And given that Eratosthenes lived during the third century BC, the stable political and social institutions of the ancient world still had hundreds upon hundreds of years to go; the wealth and growth of the ancient world was still all to come in the time of Eratosthenes. There was, in the post-Eratosthenean world, plenty of wealth, plenty of time, and plenty of intelligent individuals who could have followed up upon the work of Eratosthenes as Mersenne and Riccioli followed up on the work of Galileo, and the Apostles of Linnaeus followed up on the first research program of scientific botany. But none of this happened. The scientific knowledge that Eratosthenes formulated was preserved by others and repeated in a few schools, but no one picked up the torch and ran with it.

Why did no Eratosthenean scientific research program appear in classical antiquity? Why did scientific research programs appear during the scientific revolution? I cannot answer these questions, but I will note that these questions could constitute a scientific research program in history, which continues today to be weak in regard to scientific research programs. History today is in a state of development similar to natural science in medieval universities, before the scientific revolution. This suggests further questions. Why was there was scientific research program into logic that has been continuous throughout the history of western civilization (including the Middle Ages, which was particularly brilliant in logical research)? Why has history escaped, so far, the scientific revolution?

. . . . .

. . . . .

. . . . .

. . . . .

. . . . .

. . . . .

. . . . .

The Achievement of Columbus

12 October 2020

Monday

There is a list on Wikipedia of seventy European and American voyages of scientific exploration from the French Geodesic Mission of 1735-1739 to the Valdivia mission of 1898-1899. This list does not include the voyages of exploration during the Age of Discovery, but these voyages of exploration, while not organized for strictly scientific purposes, did constitute, among other things, a form of scientific research. One could say that exploration is a form of experimentation, or one could say that experimentation is a form of exploration; in a sense, the two activities are mutually convertible.

Late medieval and early modern voyages of discovery were undertaken with mixed motives. Among these motives were the motives to explore and to discover and to understand, but there were also motives to win new lands for Christendom and to convert any peoples discovered to Christianity, to find riches (mainly gold and spices), to obtain titles of nobility, and to seize political power. Columbus sought all of these things, but it is notable that, while he did open up the New World to Christian conversion, economic exploitation, and the unending quest for power, he achieved virtually none of these things for himself or for his heirs, despite his intentions and his efforts. Columbus’ lasting contribution was to navigation and discovery and cartography, while others exploited the discoveries of Columbus to receive riches, glory, and titles.

Although I can attempt to assimilate the voyages of Columbus to the scientific revolution, there is no question that Columbus conceptualized his own life and his voyages in providential terms, and his motives were only incidentally scientific if scientific at all. Certainly Copernicus, Galileo, Kepler, and others also had mixed motives, and indeed a mixed mindset arising from the collision of a medieval conceptual framework with early modern discoveries that added to this conceptual framework while challenging it, and eventually destroying it. Of these early modern pioneers, Columbus had the greatest sense of mission — the idea that he was a man of a great destiny — and perhaps it was this sense of mission that prompted him to extract such spectacular concessions from the Spanish crown: the title of Admiral of the Ocean Sea and Governor General of islands discovered and these titles to be inherited in perpetuity by his heirs. If Columbus’ plan had unfolded according to his design, the entirety of the Americas today would still be ruled by the descendants of Columbus.

The Age of Discovery was part of the Scientific Revolution, the leading edge of the scientific revolution, as it were, thus part of the origins story of a still-nascent scientific civilization. Today we still fall far short of being a properly scientific civilization, and how much further the European civilization of the time of Columbus fell short of this is obvious when we read Columbus’ own account of his explorations and discoveries, in which he insists that he found the route to India and China, and he insists equally on the large amount of gold that he found, when he had, in fact, discovered very little gold. Despite this, Columbus is, or deserves to be, one of the culture heroes of a scientific-civilization-yet-to-be no matter how completely he failed to understand what he accomplished.

. . . . .

To celebrate Columbus Day I visited one of my favorite beaches on the Oregon coast, Cape Meares. While yesterday, Sunday, was stormy all day, with strong winds and heavy rain, today was beautiful — warm with no wind, a blue sky, and even the ocean was not as cold as I expected when I walked in the surf. When I arrived there were only three people on the beach besides myself; when I left, there were about ten people on the beach.

. . . . .

Happy Columbus Day!

. . . . .

. . . . .

. . . . .

. . . . .

. . . . .

. . . . .

. . . . .

Happiness: A Tale of Two Surveys

4 October 2020

Sunday

The happy people of Togo.

The World Happiness Report has been published for every year since 2012 (with the exception of there being no WHR for 2014) by the Sustainable Development Solutions Network. A number of influential persons are involved in the report (e.g., the economist Jeffrey Sacks), there is big money behind the effort (e.g., sponsorship from several foundations and companies), and there are several major universities associated with the effort (Columbia, UBC, LSE, Oxford). Of course, the UN is involved also, via the Sustainable Development Solutions Network, and the report itself incorporates extensive discussions of the UN Sustainable Development Goals. Each year when the WHR is published there are predictably celebratory reports in the legacy media, along with the equally predictable hand-wringing and pearl-clutching in regard to the countries that occupy the bottom of the list.

Happy children in Togo.

With so much talent and money and reputation involved, the report not surprisingly has a sophisticated methodology. Indeed, the methodology is so sophisticated that it might be called “opaque”; I had to spend quite a bit of time reading the fine print to figure out how it was that they were coming up with their happiness rankings. Of course, the reports in the media feature the rankings, and only the merest cursory description of the methodology. In this, the WHR is incredibly effective in promoting a narrative of national success and failure without many people looking into the guts of their happiness machinery.

More happy people in Togo.

The WHR each year starts out with an explanation of the Cantril Ladder, which seems prima facie to be a relatively straight-up measure of subject well-being. The Cantril Ladder asks survey participants, “…to value their lives today on a 0 to 10 scale, with the worst possible life as a 0 and the best possible life as a 10.” (2015 WHR, p. 20) The Cantril Ladder, however, is only the beginning of the fun. The number they derive from the Cantril Ladder question is then run through six different equations, each of which brings another factor into the “happiness” calculation. The six additional factors are “GDP per capita, social support, healthy life expectancy, freedom to make life choices, generosity, and freedom from corruption.” (p. 21)

More happy children in Togo.

Of these six factors, two — per capita GDP and healthy life expectancy — are “hard” numbers for economists (in other words, they are relatively hard numbers, but these numbers can be gamed as well). Two factors require additional questions that probe subjective well-being, and these are social support and freedom to make life choices. To assess social support respondents were asked, “If you were in trouble, do you have relatives or friends you can count on to help you whenever you need them, or not?”; to assess freedom to make life choices, respondents were asked, “Are you satisfied or dissatisfied with your freedom to choose what you do with your life?” The remaining two factors are a bit squishy — generosity and freedom from corruption — by which I mean that there are measurements that could be taken for these, but subjective perceptions can also be involved. To measure generosity respondents were asked, “Have you donated money to a charity in the past month?” This strikes me as a good metric. To measure corruption respondents were asked, “Is corruption widespread throughout the government or not?” and “Is corruption widespread within businesses or not?” This strikes me as much less satisfactory, especially since bodies like Transparency International have made an effort to compile corruption indices, but it is a good measure in so far as it is more self-reported well-being data.

Yet more happy people in Togo.

Once the numbers are crunched according to their formulae, the 2015 WHR ranks the following as the ten happiest countries in the world:

1. Switzerland (7.587)

2. Iceland (7.561)

3. Denmark (7.527)

4. Norway (7.522)

5. Canada (7.427)

6. Finland (7.406)

7. Netherlands (7.378)

8. Sweden (7.364)

9. New Zealand (7.286)

10. Australia (7.284)

One cannot but notice that these are all western, industrialized nation-states, mostly European, and indeed mostly northern European.

More happiness in Togo.

In the same 2015 WHR, Togo comes in dead last. Do I believe that the people of Togo are the least happy on Earth? No, I don’t. However, I do believe that well-meaning philanthropic foundations believe that Togo needs to change, and that it especially needs the “help” of these philanthropic foundations to better acquaint them with the UN Sustainable Development Goals, so that they, too, can be made as happy as the northern European countries that top the WHR. I’m certainly not saying that everything in Togo is fine and dandy. There was serious political unrest in the country in 2017-2018 (cf. 2017–2018 Togolese protests), but, given what we delicately call the “social unrest” in the US during the summer of 2020 (also known as riots, vandalism, looting, arson, assault, and murder), I’m not sure that things are worse in Togo than the US, even if Togo is objectively impoverished compared to the US.

“Beer is proof that God loves us and wants us to be happy.”

Now, being myself from northern European stock (Norwegian on my father’s side and Swedish on my mother’s side), I could point with pride to the narrative of national success for Scandinavia that is a common feature of international comparisons of this kind, except that, being culturally Scandinavian, and having traveled in these countries, I know what the people are like. I feel very familiar in this context, and, frankly, I enjoy being in Scandinavia and being among other Scandinavians, with whom I share much in terms of temperament and attitude to life. I have also traveled in southern Europe and experienced the very different pace and temper of life, as well as the different pace and temper of life in South America, where I have traveled extensively. I have not (yet) had the good fortune to travel in Africa, much less to Togo itself, so I cannot speak from personal experience in regard to these peoples, but I do not doubt that they possess a full measure of well-being and life satisfaction such as only could be expressed in terms of their culture, much as well-being and life satisfaction in Scandinavia is expressed in terms of Scandinavian culture. What passes for “happiness” among wealthy, industrialized, Nordic peoples of a stoic disposition is not necessarily what would pass for “happiness” among west Africans.

Good times in Togo.

I have focused on the 2015 WHR report (which is not the most recent) because it provides an interesting contrast to another report from 2015, which is the WIN/Gallup International annual global End of Year survey. WIN/Gallup International collaborated on these annual surveys for ten years, from 2007 to 2017. Both WIN and Gallup International are still in business, but they no longer collaborate on these annual surveys; Gallup International (GIA) is not be confused with Gallup Inc., which two are distinct polling companies. The annual End of Year (EoY) surveys can be on a variety of questions (for 2018 the EoY survey was on political leadership), but happiness has been the focus of polling on several occasions. With these EoY surveys, Gallup International takes a sample of about 1,000 persons each from about 60 countries, always including the G20 plus a sampling of other nation-states that together represent better than half of the global population.

Togolese bananas

The methodology of the WIN/Gallup International EoY 2015 survey on happiness was a lot simpler than than Byzantine methodology of the 2015 WHR. WIN/GIA asked three questions:

● Hope Index: As far as you are concerned, do you think that 2016 will be better, worse or the same than 2015?

● Economic Optimism Index: Compared to this year, in your opinion, will next year be a year of economic prosperity, economic difficulty or remain the same for your country?

● Happiness Index: In general, do you personally feel very happy, happy, neither happy nor unhappy, unhappy or very unhappy about your life?

It is an interesting feature of these questions that the first two are framed in terms of predictions — a better next year and a more prosperous next year — but at bottom all three of these questions are questions that probe the individual’s sense of subjective well-being, albeit well-being sometimes projected into the future. Moreoever, WIN/GIA’s numbers aren’t run through a number of equations that filter these measures of subjective well-being through a variety of other factors.

Home, sweet home, in Togo.

When WIN/GIA crunched their numbers, the top ten rankings of the happiest places on the planet were radically different from those of the WHR, including a significant number of wealthy, industrialized European nation-states ranked in the bottom ten of the hope, optimism, and happiness indices:

1. Colombia (85%)

2. Fiji (82%)

3. Saudi Arabia (82%)

4. Azerbaijan (81%)

5. Vietnam (80%)

6. Argentina (79%)

7. Panama (79%)

8. Mexico (76%)

9. Ecuador (75%)

10. China/Iceland (74%)

We’ve already seen the very different methodologies employed by these two systems of ranking happiness around the world, so we understand how and why they differ, but what exactly does this difference mean? Bluntly, and in brief, it means that if you simply ask people if they are happy, you get results like WIN/GIA; if you run self-reported happiness through a filter of economics, you get results like WHR. Another way to frame this would be to say that the WHR implicitly incorporates Maslovian assumptions built into its rankings, such that a number of physiological and social needs must be met before we can even consider the question of happiness; if we interpret happiness as a form of self-actualization, we can see the relevance of Maslow’s hierarchy of needs to sophisticated rankings of happiness that incorporate many other factors.

How much weight should we give to self-reported well-being? Should we be factoring in metrics other than subjectively reported happiness in attempting to measure happiness? Are individuals not their own best judge of their own happiness? There is a certain irony involved in economists assuming that individuals are not their own best judge of their own happiness, as it is economists who are always telling us that individuals are always the best judge of how their own earnings should be spent, because an individual exercises a close and careful oversight over money he himself has earned, while governments collecting money through taxes are spending money they did not themselves earn, and so are likely to exercise less stringent oversight.

More to the point, should elaborate polling methodologies with a pretense to represent self-reported well-being, but which in fact represent economic measures, drive analysis and policy? If we are to take happiness rankings as the basis of policy prescriptions, as the WHR position their study, but using the WIN/GIA numbers instead, then clearly the nation-states of the world should be emulating Colombia, Saudi Arabia, Vietnam, and Argentina. One might then conclude that the way to national happiness is surviving a 50 year civil war, capital punishment by beheadings in the street, having a one-party communist dictatorship, or having the largest sovereign debt default in history. The economists studying happiness would probably see such policy prescriptions as moral hazards. One suspects that the authors of the first WHR in 2012 saw the raw Cantril Ladder data, knew that it wasn’t going to give them the results that they wanted, and realized that they had their work cut out for them. For someone who knows how to crunch numbers, and who could get the raw data from which the WHR is compiled, it would be an interesting exercise to see exactly how much subjective well-being made any difference at all in the rankings.

If we take only per capita GDP in 2015 this is the top ten ranking:

1. Luxenbourg

2. Switzerland

3. Macao SAR

4. Norway

5. Ireland

6. Qatar

7. Iceland

8. US

9. Singapore

10. Denmark

We can immediately see that this list shares four entries with the WHR list — Switzerland, Iceland, Norway, and Denmark — while it shares only one entry with the WIN/GIA rankings — Iceland ties with China for tenth place in the WIN/GIA happiness index. From this we can see that GDP alone is 40% the same as the WHR rankings. To me this makes the WHR look more like factoring in some sense of subject well-being into economic rankings than it looks like factoring some economic data into self-reported happiness. Why not then simply use per capita GDP as a rough approximation for “happiness”? My speculation: economists already have to deal with ideas like homo economicus and the invisible hand, which are routinely chastised as being a vulgarly reductionist approach to the human condition; if happiness is to be characterized in economic terms, it needs to be done with style, verve, and not a little obfuscation if it is going to be carried off successfully in such a climate.

If one is going to indulge in the pleasant fantasy that public policy can be driven by concerns of individual well-being, one needs to be hard-headed about it if one’s policy proposals are to stand half a chance. The kind of people who formulate UN Sustainable Development Goals are content with the rankings of the WHR as a guide to policy, because it affirms their narrative, but the WIN/GIA rankings are effectively “opposite world” for the same people, and certainly not a guide to policy. If the happiest people in the world are to be found in Saudi Arabia and Azerbaijan, and with the people of Bangladesh and Nigeria topping the Hope Index, then UN measures of what constitutes the good life and hope for the future are more than a little off. And the WHR insists on UN Sustainable Development Goals almost to the point of salesmanship.

While I haven’t here fully showed you how the magic trick is done (I lack the expertise for that), I hope that I’ve showed you enough that the next time you see WHR rankings reported in the media, you will be skeptical of the relationship of these rankings to actual human happiness, which is certainly affected by economics, but is not identical with economics, and, moreover, there can be important outliers such that nearly optimal human happiness may occur with little or no relationship to economic measures that we might be tempted to substitute for happiness. Certainly, again, “well-being” is more than happiness, and economics makes a generous contribution to well-being, but when we use “well-being” as a rough synonym for happiness, and then rightly define well-being (in its other sense, not specifically related to happiness) by economic measures, this is the essence of the magic trick, and such a sleight of hand is not to be believed. I should sooner believe that all the people in Togo are miserable than believe that the contribution of happiness to well-being can be artfully dissimulated.

. . . . .

. . . . .

. . . . .

. . . . .

. . . . .

. . . . .

. . . . .

When a Civilization Retreats

20 August 2020

Thursday

A Case Study of Norse Civilization

And Some Reflections on the Methodology of the Study of Civilization

Usually when a civilization goes into decline, its geographical extent contracts at the same time as its social and political institutions lose complexity, so that contraction and loss of complexity are correlated for causal reasons. One could distinguish the cases in which territorial contraction (perhaps caused by aggression by a neighboring power) causes loss of institutional complexity, and those cases in which the loss of institutional complexity causes the loss of territory.

Viking exploration in the North Atlantic.

While the correlation of institutional collapse and territorial contraction is a common one of decline, there may be cases in which geographical contraction can be isolated from loss of institutional complexity, so that a civilization might experience geographical contraction without loss of institutional complexity, or loss of institutional complexity without experiencing geographical contraction. In the latter case of a loss of complexity without geographical contraction, the sudden, catastrophic failure of a civilization would fulfill this condition, as such a sudden and catastrophic failure would leave no time for the civilization to contract. The former case of geographical contraction without loss of institutional complexity is what I have in mind in invoking the idea of civilization in retreat.

If I can further invoke Norse civilization as a distinct historical entity, more comprehensive than Viking civilization, as it would have spanned both the Viking period and the period of early Christian Scandinavia, before the Scandinavian kingdoms were more closely integrated into continental European civilization, we could then speak of a period of civilization in northern Europe comprising almost a thousand years of largely autonomous civilizational development. The construct of Nordic civilization would also span the difference between the partially nomadic Viking civilization, with its central project to be found in voyaging, raiding, and trading, and the later more settled, Christian iteration, in which the distinctive mythology of Scandinavia was abandoned, as was the voyaging, raiding, and trading for the most part.

Norse civilization during the Viking period expanded west across the North Atlantic during the period that we now call the Medieval Warm Period (or the Medieval Climate Optimum), from about 950 to 1250 AD. These unusual conditions allowed Norse longships to cross the North Atlantic and to established colonies in Greenland and L’Anse aux Meadows on Newfoundland, thus making it all the way to North America. The Norse presence on Greenland and Newfoundland was never large — we could say that it was not demographically significant, unlike, e.g., the Norse presence in Iceland — but the Norse settlements on Greenland endured for hundreds of years (from about 980 to 1409 AD), with several thousand residents and about four hundred farms identified by archaeologists. While the earlier warm period made travel and agriculture in the North Atlantic possible, the subsequent cooling known as the Little Ice Age (1300 to 1850) made both more difficult.

Viking ruins on Greenland.

We can imagine an alternative history in which the climate optimum endured for a longer period of time, and Norse settlements in Greenland and Newfoundland grew into cities and eventually into an outpost of Norse civilization capable of surviving through adverse climate conditions, and which could work its way down the coast to the bulk of the Americas, in the same way that the Spanish, and later the Dutch, British, French, and Portuguese explored north and south from Columbus’ first landings in the Caribbean. Norse civilization continued on Iceland, and one could argue that it entered its most brilliant period even as the territorial extent of Norse civilization was contracting, as most of the Icelandic saga literature was written during the 13th and 14th centuries, after the end of the Medieval Warm Period, when we can infer that life on Iceland became more difficult than it had been in preceding centuries.

An early map of Iceland.

As with the later Homeric account of heroes during the Greek dark ages, the Icelandic saga literature was written hundreds of years after the fact to celebrate the deeds of earlier men, though the Viking protagonists of many of these sagas are only distantly related (in a literary sense) to the heroic paradigm among the Greeks. What is consistent is that the deeds and achievements of men during a period of marginal literacy were later recounted during an age of more established literacy, and that deeds of Norse warriors were celebrated in Skaldic poetry as the deeds of Greek warriors were celebrated in Homeric poetry.

The history of Norse civilization taken whole involves the submergence of its earlier form — we could say that the Christianization of the Scandinavians was a process of submergence that unfolded over almost five hundred years, and, after that process was complete, Scandinavia was fully incorporated into continental European civilization and no longer represented a distinct civilization. In other words, Norse civilization underwent a complete institutional transformation — the transformation of its economic infrastructure (from raiding and trading to manorial agriculture), its conceptual framework (from a framework inherited from iron age paganism to the template provided by post-Axial Christendom), and its central project (from Norse mythology to Christian mythology) — and, by the time that transformation was complete, Norse civilization had vanished. Either Norse civilization was then extinct, or it had become permanently submerged.

There is considerable evidence of the period during which ideas of Viking mythology and Christianity were both found in Norse society (i.e., the period of institutional transformation). There is a casting mould with spaces for two crosses and one Thor’s hammer (above), so that an enterprising manufacturer of jewelry could serve both the pagan and Christian markets (cf. Christianity comes to Denmark). Both headstones and grave goods have both pagan and Christian symbols. The earliest Christian art in Scandinavia is Viking in character, as in the Jelling stone depiction of Christ surrounded by elaborate woven motifs found in Viking art; such patterns are also found in the carved decoration of Stave churches in Norway, especially at Urnes. It has also been observed that some jewelry of the period can pass as either a cross or Thor’s hammer (cf. Thor’s Hammers Disguised as Crucifixes), which could constitute a subtle form of resistance against imposed Christianity (below).

The conceptual framework of Christendom that Viking civilization took over with Christianization was more complex than the conceptual framework of the Vikings themselves, so that the transformation within Norse society involved an increase in complexity of the conceptual framework. Christianity by this time already possessed a millennium of Christian-specific scholarship, as well as possessing a growing network of universities in continental Europe that were in the process of assimilating the intellectual heritage of classical antiquity, and synthesizing this with the Christian tradition.

The economic infrastructure of the Vikings was complex, with trade networks extending from Greenland to Constantinople; no trading network of this scope and scale could have survived over hundreds of years without considerable intelligent management. Whether the transition to manorial agriculture represented a decrease in economic complexity, once the Norse were no longer free to plunder from other Christian peoples, is a question that could only be answered by a detailed survey and comparisons of the economic institutions of these two phases of Norse civilization. However, it should be observed that, shortly after Christianization, Scandinavians were drawn into the trading network of the Hanseatic League, so that it is likely that native commercial talent and any remnant of trading expertise from the Viking period would have been funneled into this outlet with little loss of complexity. (We do not at present have a method for assessing the economic complexity of historical societies, though there are many possible measures that might be adopted; considerable research would be involved in the application of any metric chosen as a proxy for economic complexity.)

The author with another side of the runic stone in Jelling, Denmark, May 1988.

The central project of Viking mythology and Christian mythology are probably within the same order of magnitude of complexity. The considerable advantage that Christianity had in terms of an explicitly elaborated theology belongs to the conceptual framework rather than to the central project proper. That great distinction between the two is qualitative, rather than quantitative. Christianity belongs to the class of post-Axial Age religious traditions (like Buddhism before and Islam after) that emphasized the transformation of the individual moral consciousness upon conversion, and which actively invested resources in proselytization, in order to more effectively and widely attain that transformation of the individual moral consciousness, achieving a networking of the faithful through shared personal experience. Viking mythology belongs to a tradition of belief still continuous from the Neolithic, and, before that, continuous with the Paleolithic and indeed with the origins of humanity, in which the ordinary business of life is rendered sacred through ancient rituals of unknown origin. There is no conception of the transformation of the individual moral consciousness, and virtually no conversion or proselytization. The argument could be made that these traditions are incommensurable, but by objective measures it would be difficult to say that one mythological tradition is more complex than the other (though it could be argued that post-Axial traditions involve greater moral complexity).

A carved stone grave marker outside the ruins of Lindisfarne Priory depicts a row of Viking raiders.

Viking civilization was expansionary from at least 789 (with the Viking attack on the Isle of Portland) through the early years of the 11th century, when Christianization began the transformation of Viking civilization into Norse Christian civilization. Arguably, Christian civilization was expansionary from 312 AD (the Battle of the Milvian Bridge, when Constantine the Great came into complete control of the Roman Empire, until the late 19th or early 20th century (with the final efflorescence of expansionary Christianity being the “muscular Christianity” of the British Empire). While it is relatively easy to understand how the exhausted paganism of late antiquity gave way before a youthful and energetic Christianity, it is more difficult to understand the conversion of the Vikings by a faith already a thousand years old. The longer expansionary trajectory of a larger and more complex Christian civilization may explain why the vigorous paganism of the Vikings gave way to Christian conversion.

Viking civilization ceased to be expansionary at some time in the 11th century, and with the onset of the Little Ice Age the territorial extent of that civilization, now transformed into Norse Christian civilization, contracted. The final date we have for the Norse on Greenland is 1409, though it is believed that some of the settlements may have continued to about 1500 (cf. McGovern, T. H. 1980. Cows, harp seals, and churchbells: Adaptation and extinction in Norse Greenland. Human Ecology, 8(3), 245–275. doi:10.1007/bf01561026). In other words, records of the Norse in Greenland suggest that there were Norse still living in Greenland up to the time that Christopher Columbus sailed to the New World, inaugurating a new period in human history. I find it a remarkable reflection that as one era of European settlement of the New World was coming to an end, another era of European settlement of the New World was only beginning.

When Columbus sailed for the New World there are probably still Norse settlers living on Greenland.

But there is more that can be gleaned from the experience of Norse civilization (if we allow such a construction) than its contraction simultaneous with Iberian expansion. I began this essay with the idea of using the example of the Norse retreat from Greenland and Newfoundland as an example of the retreat of a civilization from its territorial maximum, without loss of institutional complexity, but the history of the expansion and contraction of Norse civilization suggests lessons for the method of the study of civilization overall.

Of methods for the study of civilization Johann P. Aranson wrote:

“No representative author has ever suggested that civilizational analysis should develop a methodology of its own. There are no good grounds for attempting anything of the kind.”

“Making Contact and Mapping the Terrain” by Johann P. Arnason, in Anthropology and Civilizational Analysis: Eurasian Explorations, edited by Johann P. Arnason and Chris Hann, Albany: SUNY Press, 2018, p. xvi

Aranson’s point is not that we shouldn’t study civilization on its own merits, but the study of civilization is intrinsically inter-disciplinary and therefore no methods unique to the study of civilization need be formulated. I reject this claim. The most obvious example of a methodology specific to the study of civilization is the comparative method. Philip Bagby subtitled his Culture and History, “Prolegomena to the Comparative Study of Civilization.” Indeed, there is a journal specifically devoted to this, the Comparative Civilizations Review published by The International Society for the Comparative Study of Civilizations (ISCSC). A 1996 paper in this journal, “Methodological Considerations for the Comparative Study of Civilizations” by John Mears (Mears, John. 1996. “Methodological Considerations for the Comparative Study of Civilization,” Comparative Civilizations Review: Vol. 34: No. 34, Article 2), highlights the concern for methodology. This would seem to be a paradigm case of civilizational analysis developing a methodology of its own, but the fact that there is so little communication between ISCSC and scholars who now use the term “civilizational analysis” to describe their work is typical of the extreme Balkanization of the study of civilization. The historians don’t read the sociologists, the sociologists don’t read the anthropologists, and the anthropologists only read those archaeologists who are counted as part of the “four-field approach” to anthropology.

One could argue that there is nothing about the comparative method that is distinctive about civilization; taxonomists have been discussing comparative anatomy for centuries. This is true. One also could make the claim that what is distinctive is that the object of comparison is civilization, and not some other object of knowledge. This is true also. But perhaps this is not a fruitful line of inquiry, so we will leave it for now, marked for possible consideration at a later date.

Whether or not the comparative method in the study of civilization is a distinctive methodology, and whether or not it is a distinctive methodology for the study of civilization in particular, and, as a distinctive methodology, constitutes a methodology specific to the study of civilization, my above exposition of the concept of Norse civilization, which is comprised of both Viking civilization and distinctively Norse Christian civilization, does suggest a methodology peculiar to the study of civilization.

We can distinguish two movements of thought in the attempt to capture the picture of a civilization, which I will call upward construction and downward analysis (not the best terminology, I will acknowledge, but hopefully the meanings will be intuitively obvious once explained). In upward construction, we ascend from the historical particularity of a given civilization to more comprehensive civilizational formations of which the civilization from which we started is a part, or an expression. In downward analysis, we descend from the formation of civilization with which we began to some civilizational minimum that represents one expression (usually one among many) of the formation with which we began.

In the spirit of upward construction, we have already brought together Viking civilization and Norse Christian civilization into a larger whole of Norse civilization of which both were a part. Continuing the constructive ascent, we would show Norse civilization as a part of European civilization, European civilization as a part of western civilization, and western civilization as a part of planetary civilization. At our present stage of development, upward construction terminates at the planetary scale, although if humanity becomes a spacefaring multi-planetary species, upward construction will expand into more comprehensive formations of civilization beyond the planetary.

Reconstruction of a Viking settlement at L’Anse aux Meadows on Newfoundland.

In the spirit of downward analysis, we descend to the smallest units of civilization within Norse civilization (or any civilization so subjected to analysis), so that we might identify a Newfoundland Norse civilization or a Greenland Norse civilization. The Secrets of the Dead episode “The Lost Vikings” called the Norse settlements on Greenland a “once prosperous civilization,” so this is not unprecedented. While few would be likely to individuate a distinctive Newfoundland Norse civilization, probably there would be little objection to identifying a distinctive Icelandic Norse civilization. The details of our definition of civilization — specifically, the quantification of institutions — would determine the civilizational minimum by which we would individuate a distinctive civilization.