Acceptance and Commitment Therapy For Children

Acceptance and Commitment Therapy For Children

Uploaded by

ClaudiaCopyright:

Available Formats

Acceptance and Commitment Therapy For Children

Acceptance and Commitment Therapy For Children

Uploaded by

ClaudiaOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Copyright:

Available Formats

Acceptance and Commitment Therapy For Children

Acceptance and Commitment Therapy For Children

Uploaded by

ClaudiaCopyright:

Available Formats

Author's Accepted Manuscript

Acceptance and commitment therapy for

children: A systematic review of intervention

studies

Jessica Swain, Karen Hancock, Angela Dixon,

Jenny Bowman

www.elsevier.com/locate/jcbs

PII: S2212-1447(15)00004-6

DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jcbs.2015.02.001

Reference: JCBS80

To appear in: Journal of Contextual Behavioral Science

Received date: 31 March 2014

Revised date: 20 December 2014

Accepted date: 11 February 2015

Cite this article as: Jessica Swain, Karen Hancock, Angela Dixon, Jenny

Bowman, Acceptance and commitment therapy for children: A systematic

review of intervention studies, Journal of Contextual Behavioral Science, http://dx.

doi.org/10.1016/j.jcbs.2015.02.001

This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for

publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of

the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and

review of the resulting galley proof before it is published in its final citable form.

Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which

could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal

pertain.

Title: Acceptance and Commitment Therapy for children: A systematic review of intervention

studies

Author names/affiliations: Jessica Swain a, b, Karen Hancock a, b, Angela Dixon a, Jenny

Bowman b

a

Department of Psychological Medicine, The Children’s Hospital at Westmead, Sydney NSW

2145

b

School of Psychology, The University of Newcastle, Newcastle NSW 2308

Corresponding author: Jessica Swain; Ph: +61 410 452 140; E: [email protected]

Current postal address: Jessica Swain Mental Health & Psychology Section, Lavarack Health

Centre, Lavarack Barracks, Townsville QLD Australia 4813

Introduction

Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT) is a contemporary behavioural and cognitive

therapy that works to foster increasing flexibility in response to thoughts, feelings and sensations

through processes of mindfulness, acceptance, and behaviour change (S. C. Hayes, Levin,

Plumb-Vilardaga, Villatte, & Pistorello, 2013; Wilson, Bordieri, Flynn, Lucas, & Slater, 2011).

In ACT the focus of change interventions is the context in which psychological phenomena

occur, rather than the direct change attempts of their content/validity or frequency, as typified by

traditional cognitive behaviour therapy (CBT; Blackledge, Ciarrochi, & Deane, 2009; S. C.

Hayes, 2004; S. C. Hayes, Villatte, Levin, & Hildebrandt, 2011).

ACT is underpinned by a theoretical framework, termed relational frame theory (RFT; S. C.

Hayes et al., 2011). RFT focuses on human language and cognitive processes and suggests that

with language development we learn to continually derive relations between events. From

childhood we learn to relate events to each other on the basis of social convention and to derive

meaning from events on the basis of this relating, termed in ACT “learned derivation” (Luoma,

Hayes, & Walser, 2007). For example, during early language training interactions, children are

often shown objects and asked to repeat their names. A mother may then clap her hands, or say,

“That’s right, a car!”, reinforcing the spoken word “car” with the object, car. The child may also

be taught the name of the car, so object-word and word-object relation is explicitly trained. With

sufficient repetitions learned derivation occurs. The child is then able to generalise the spoken

word car to a toy car, and to the printed words “toy car”, and vice-versa.

Whilst learned derivation offers evolutionary advantages, it can also act as a hindrance. When

language is taken literally this can result in a “fusion” with thinking (i.e. experience one’s own

thoughts and beliefs as literally true), and can lead to pain (Harris, 2009). In ACT this is termed

cognitive fusion. To illustrate, fusing with the thought that “life is unbearable” might produce

depressive symptoms despite the existence of various things required to live a full life, such as

meaningful employment and supportive relationships (S. C. Hayes, Pistorello, & Levin, 2012).

Cognitive fusion in turn leads to a whole host of reactions, known as “experiential avoidance”,

such as excessive use of problem solving, active efforts to escape or avoid feelings, and

entanglement in thinking; methods employed as a way to solve our pain (Luoma et al., 2007).

These methods result in a loss of contact with the present, belief in negative stories about

ourselves, and rigidity in our way of living. Life becomes less about opening up in the pursuit of

things that are important, but tends to result in an overall narrowing of living to support freedom

from distress (Harris, 2009). In ACT this is termed psychological inflexibility.

ACT employs six interrelational core therapeutic processes that form a “hexaflex” model of

psychological flexibility; acceptance, cognitive defusion, mindfulness, self-as-context,

committed action, and valued living (Luoma et al., 2007). Acceptance is employed as the

antithesis to experiential avoidance. The focus is on opening up to thoughts, feelings and

sensations in order to increase the behaviour repertoire and allow for action that is in line with

what is important (S. C. Hayes et al., 2012). To counteract cognitive fusion, clients learn to

change the way they relate to their thoughts, and thereby decrease their attachment to these. For

children, metaphors and experiential exercises help the child recognise a thought for what it is,

just a bunch of words, and not what it says it is. Mindfulness is utilised to reduce problematic

attentional patterns, that are past focused or future orientated (S. C. Hayes et al., 2012), in order

to reduce cognitive errors such as rumination (past) or catastrophising (future). Clients are taught

mindfulness approaches to increase their skills in staying present focused. Approaches may

range from formal meditation exercises to deliberately averting “auto-pilot” by deliberately

focusing on the here-and-now experience of activities of daily living such as breathing, walking

or riding a bike (Harris, 2009). Self-as-context is best conceptualised as a perspective taken from

the sense of self, or the ability of humans to consciously notice themselves doing, thinking or

experiencing things whilst they are occurring. Therapeutically, contact with the self-as-context is

achieved via mindfulness and perspective-taking (S. C. Hayes et al., 2012). Values identification

is employed to assist in living life the way that is meaningful to each individual, supporting the

identification of those tenets that may act as a compass to future action and as intrinsic

reinforcers to the continuation of this behaviour (S. C. Hayes et al., 2012). For children this is

working through what really matters to them at school, home and/or in their friendships for

example. Committed action advocates engaging in behaviour that is in line with personal values

for living, moment-by-moment, this often takes the appearance of behaviour change goals such

as behavioural activation or exposure (S. C. Hayes et al., 2012). These approaches from the

hexaflex are deployed to foster the attainment of increasingly flexible methods of managing

challenging cognitions, emotions or sensations, thereby diminishing their deleterious behavioural

consequences (Arch & Craske, 2008).

ACT has a growing evidence base in the treatment of adult psychopathology, with numerous

reviews and meta-analyses demonstrating its efficacy (e.g., S. C. Hayes, Luoma, Bond, Masuda,

& Lillis, 2006; Levin & Hayes, 2009; Ruiz, 2012). There has also been considerable interest in

the adaptation and assessment of the suitability of ACT approaches among child and adolescent

populations (e.g., Coyne, McHugh, & Martinez, 2011; Greco, Blackledge, Coyne, & Ehrenreich,

2005; Murrell & Scherbarth, 2006). Reviews have found other psychotherapeutic approaches,

such as traditional CBT, to be effective in the treatment of children with various presenting

problems (AACAP, 2007, 2012; James, James, Cowdrey, Soler, & Choke, 2013; Weisz,

McCarty, & Valeri, 2006). However, their effectiveness has been found to be modest (Weisz et

al., 2006) and/or superior to no treatment, but not active control conditions (James et al., 2013).

Finally, a recent review concluded that CBT is not necessarily the most effective form of

treatment for young people, but the only one that has been researched enough to provide

evidence to support its use (Creswell, Waite, & Cooper, 2014). Thus there is room for

improvement and there is a need for more rigorous research into alternative treatments to support

evidence based clinical practice.

Stemming from the cognitive behavioural tradition and with a strong theoretical basis, ACT has

been proposed as a transdiagnostic therapy, a unified treatment applicable to a range of

presenting problems and clinical diagnoses (S. C. Hayes et al., 2012; Livheim et al., 2014). One

possible mechanism through which this may occur is via ACT’s focus on experiential avoidance.

A recent review linked experiential avoidance to an array of psychopathology, finding

experiential avoidance predicts symptom severity in specific disorders, affects relapse and can

act as a mediator for psychological distress and coping (Chawla & Ostafin, 2007). If ACT were

found to work effectively as a transdiagnostic approach this would reduce the load on clinicians

to gain familiarity and competence with a whole host of diagnosis-specific evidence-based

intervention (Farchione et al., 2012). This lends itself to the potential to work across contexts,

with diverse child and adolescent populations and for clinicians to readily increase their expertise

in intervention delivery.

More research incorporating ACT processes of change is required, including into experiential

avoidance, to better elucidate this, particularly among children. Research on the ACT core

processes and their relation to QOL, or psychosocial and well-being outcomes, among children

demonstrates that these processes operate in a similar way to that of adults (for a review see

Coyne et al., 2011). Feasibility studies also offer support for the utility of mindfulness-based

approaches, such as ACT, with children (Burke, 2010). It has been argued that as children think

less literally than adults, the employment of metaphors and experiential approaches may allow

children to grasp abstract concepts through experience (O'Brien, Larson, & Murrell, 2008).

Preliminary research with children as young as four suggests provides some evidence for this

assertion (Heffner, Greco, & Eifert, 2003). Furthermore, it has been purported that children have

had less time to adopt more entrenched patterns of experiential avoidance and as such, ACT may

operate to achieve both the remediation, and prevention, of the onset of inflexible patterns of

psychological responding (Greco et al., 2005). ACT approaches may also be well-suited to

adolescents as they assist in rapport building and are less instructive (Greco et al., 2005). ACT’s

focus on experiential, or personal learning, approaches support autonomously-driven behaviour

that may be particularly appropriate for adolescents desiring increased independence who may be

non-responsive to adult direction (Hadlandsmyth, White, Nesin, & Greco, 2013). The emphasis

on values may also be pertinent for adolescents due to the exploratory nature of, and increasing

capacity for abstract thinking during, this developmental period (Greco et al., 2005).

There are two existing reviews of the ACT literature among children, however, neither have been

conducted systematically. Systematic reviews of psychotherapeutic research aim to synthesise

the academic literature, using a predefined scientific method to answer a specific clinical

question, whilst minimising bias, and support the delivery of evidence-based treatment (Mulrow,

1994). Systematic reviews also identify and analyse the methodological rigor of included studies

to support clinician’s to comprehend the validity of the findings to their clients as well as support

the conduct of future research endeavours (Mulrow, 1994). Both existing reviews of the ACT

literature for children Murrell and Scherbarth (2006) and Coyne et al. (2011) examined 15

studies, which incorporated unpublished data from conference presentations not subjected to

peer-review, parenting interventions, theoretical studies, and a study with an absence of

psychometric measures. Neither examined unpublished university theses or dissertations. Whilst

exclusive reliance on published literature in reviews may produce publication bias (McLeod &

Weisz, 2004), potentially overstating the positive nature of treatment results, it has been argued

that unpublished studies are unsuitable for systematic reviews due to their inferior

methodological rigour. However, studies that have examined the rigour of grey literature,

academic unpublished literature that has not been subjected to widespread peer review by the

scientific community, have found that theses and dissertations may contain more, or

equivalently, stringent methodology than that found within published studies (Hopewell,

McDonald, Clarke, & Egger, 2007; McLeod & Weisz, 2004). Whilst any form of unpublished

academic literature might be considered to be grey literature, theses and dissertations have the

advantage of undergoing peer review from a (albeit, small) number of reviewers. Therefore, it

would seem that unpublished theses and dissertations have the capacity to reduce publication

bias, whilst maintaining methodological quality, and strengthen the empirical base into

populations for which there is a paucity of research. In this way, a systematic review supports

clinicians and researchers to benefit from the synthesis of a greater wealth of research where bias

is minimised to support translation into clinical and academic practice.

Evaluation of the methodological stringency of ACT research may be particularly salient, as a

previous systematic review and meta-analysis of the adult literature, concluded methodological

concerns are more typical in ACT research than in traditional CBT and that ACT did not met the

requirements to be an “empirically supported treatment” (Ost, 2008). However, the conclusions

of this review are not without contention. Gaudiano (2009) argued that the strategy utilised by

Ost to compare methodological quality of ACT and CBT was mismatched, with the majority of

ACT studies conducted among populations widely acknowledged to be treatment-resistant. ACT

and CBT were also noted to be at markedly different stages of clinical trial research and

associated grant support, favouring CBT, which was moderately correlated with methodological

rigour (Gaudiano, 2009). Whilst this review was not without criticism, Ost was commended for

attempting to evaluate the methodological stringency of the literature when making conclusions

on its applicability for clinical practice (Gaudiano, 2009).

In summary, whilst two previous reviews of ACT for children have been conducted, these are

subject to several limitations including non-scientific approaches and the inclusion of studies that

are purely theoretical or not subjected to peer-review. At the time of the publication of the most

recent review, few empirical studies had been conducted and those that were available were

predominantly case studies or uncontrolled pilots (Coyne et al., 2011). In the past few years the

ACT literature has seen a proliferation of studies involving child and adolescent populations. As

an increasing number of studies are now available there is a growing need for a systematic

review of the utility of ACT for children. The current investigation aims to address this gap in

the literature by providing an integrated synthesis of both the published and unpublished

literature for ACT in the treatment of children that incorporates both an exploration of findings

and an evaluation of the methodological rigour of included studies. The diverse literature will be

synthesised to elucidate generalisations, consistencies and inconsistencies in research findings to

enable evidence-based clinical decision-making in this area and minimise bias (Higgins &

Green, 2011; Mulrow, 1994). The analysis of the methodological rigour of included studies will

also offer ecological validity information to assist clinicians in translating research into practice.

To the authors’ knowledge, this is the first systematic review to specifically focus upon children.

Method

Search and screening procedures

Electronic searches of the PsycInfo and PsycArticles and PsycExtra databases were undertaken

to obtain the published literature. Whilst no date restrictions were employed, the search was

conducted in December 2014 and therefore included literature available up to this time.

Considered to be an international online learning and research community for researchers and

clinicians with an interest in ACT, the Association for Contextual Behavioral Science webpage

(http://contextualscience.org/) was also searched, for the same time period. To minimise

potential publication bias, a search of the unpublished literature was undertaken via the Proquest

dissertations and theses database, up to December 2014. Search terms used were “Acceptance

and Commitment Therapy” AND “child*”, or “adolescen*”, or “teen*”. Manual searches of

reference lists were conducted for each included study, followed by citation searches to locate

additional studies for inclusion. The title and abstracts of citations attained from initial searches

and via secondary examination of reference lists were subjected to the below inclusion and

exclusion criteria by the first two authors. Where there was disagreement on eligibility, the study

was jointly reassessed by both authors to achieve a unanimous result. In the event that this could

not be reached, the third author was available to make a determination. Full papers of retained

citations were retrieved and re-subjected to the below full inclusion and exclusion criteria.

Inclusion criteria

Inclusion criteria for the current review included:

a) Intervention studies of ACT or studies that employed a minimum of two of the ACT

hexaflex processes: mindfulness, acceptance, cognitive defusion, self-as-context,

values and committed action.

b) Studies that treated child participants up to age 18 years

c) Articles prepared in English

Exclusion criteria

a) Review, meta-analysis or theoretical articles

b) Studies that lacked at least one psychometrically validated measure

To enable maximum breadth of the review no inclusion restrictions were placed on study design,

disorder or problem of interest, setting, or control/comparison condition or timeframe to follow-

up.

Eligible studies

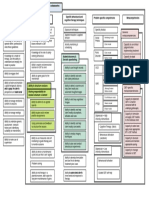

The initial search identified 169 citations (following de-duplication). An examination of

reference lists produced an additional 33 citations. Of these 202 citations, 33 met initial inclusion

criteria. Full papers were retrieved for these 33 citations. See Figure 1 for an overview of the

study selection process.

<insert figure here>

Figure 1. Selection of studies

Twenty papers met full inclusion criteria, detailing 21 unique studies. The first two authors were

unanimous with respect to eligible studies. The reasons for exclusion of the 13 papers that met

initial inclusion criteria, but were excluded after full review, are summarised in Appendix A. The

primary reason for exclusion at this stage related to the paper not reflecting an intervention trial

(i.e. theoretical papers or reviews etc.).

Data extraction, synthesis and quality assessment

Data was extracted to a standardised coding sheet for all studies meeting inclusion criteria. Data

extracted included population characteristics, setting, disorder/concern being treated, research

design, treatment conditions, treatment duration and outcomes. Outcomes of interest included: 1)

reductions in clinician-rated, parent-rated, self-reported or objective measures of a) symptoms

and/or b) QOL outcomes and/or c) psychological flexibility and; 2) maintenance of treatment

gains at follow-up. Due to the heterogeneity of studies and few with reported effect sizes, this

evaluation is limited to a narrative synthesis.

As heterogeneity of the sample studies was expected, it was important to assess methodological

quality to account for likely confounding factors. Quality assessment was conducted using the

22-item “Psychotherapy outcome study methodology rating form” (POMRF) devised by Ost

(2008). As discussed, the Ost (2008) review has some limitations, but his methodological

critique using the POMRF has been acknowledged as an important step in progressing the field

(Gaudiano, 2009). The POMRF includes 22 methodological components such as sample

characteristics, the psychometric properties of outcome measures, research design, controls,

therapist training and therapeutic modality adherence. Each item is rated on a 3-point scale

where 0 = Poor, 1 = Fair, and 2 = Good. Each study receives an overall score between 0 and 44,

with higher scores indicative of greater methodological rigour. The POMRF has good internal

consistency (0.86) and interrater reliability within the range 0.50–1.00 with a mean of 0.75 (Ost,

2008). Quality assessment data were extracted by the first two authors to a second coding sheet

developed for this purpose. Where quality assessment judgement was subject to discrepancy the

study was jointly reassessed by the two first authors to gain a unanimous result. Where this could

not be reached the third author was available to make a determination.

Results

Overview of included studies

Table 1 provides an overview of included studies. Studies included a total of 707 participants and

incorporated treatment for children with anorexia nervosa, depression, pain, trichotillomania,

sickle cell disease, tic disorders, obsessive-compulsive disorder, anxiety symptoms,

posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) / posttraumatic stress symptoms (PTS),

impulsivity/problem/sexualised behaviour, self-harm, stress symptoms, emotional dysregulation,

Aspergers Syndrome, and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Eighty percent of the studies

were published journal articles and the remaining 20% were made up of unpublished university

theses or dissertations.

Sample characteristics

Pain was the most commonly investigated condition (n=5; 23.81%) and studies employed

predominantly clinical outpatients (n=16; 76.19%). The sample size ranged from 1 to 339

participants. Overall, studies were relatively gender balanced. Participants ranged in age from 6

to 18 years, with the majority of studies conducted with adolescents (>11 years; n=17; 80.95%),

compared to younger children (<12 years; n=4; 19.05%).

Study design and treatment conditions

There were seven within-group designs (33.33%), six case studies/series (28.57%), four

between-group designs (19.04%; with two including control conditions), and the same

proportion of RCTs. The majority of studies involved individual treatment (n=14; 66.67%), with

a lesser proportion undertaken in group format (n=5; 23.8%). One was a family-based

intervention, and another did not specify the treatment format (4.76%). High heterogeneity was

observed in terms of treatment duration, with studies ranging between 5-90 hours.

Control/active comparison and random assignment

A large proportion of studies did not utilise a control comparison group (n=10; 47.62%). Of the

eleven studies that did employ a control group, five (23.8%) used a treatment-as-usual (TAU)

comparison. Two studies (n=2; 9.52%) utilised multiple baseline and, another two, baseline

control. One study employed a waitlist control, and another one did not specific the form of

control employed (4.76%). One study compared ACT with another active treatment, habit

reversal training. Overall, only the four RCTs utilised random assignment of participants to

treatment, with one further Australian study employing a random allocation for female, but not

male participants (Livheim et al., 2014).

Assessment of methodological quality

Significant variability in methodological rigour was evident with overall POMRF scores ranging

from 3-25 out of a total of 44 points, with the average score 13.29 (SD = 5.12; Table 2). As Ost

(2008) did not include cut-off scores for the POMRF, standard deviations (SD; rounded to the

nearest whole number) were utilised to attain a POMRF rating in order to compare studies, in

line with an earlier systematic review of ACT in the treatment of anxiety (Swain, Hancock,

Hainsworth, & Bowman, 2013). Swain et al. (2013) rated studies more than one SD below the

mean POMRF score “well below average” (current investigation range 0–7), those within one

SD of the mean “below average” (8-13), “above average” (14-18), and “well above average”

(19+). See Table 2 for POMRF scores and ratings.

Many methodological components were ignored by the studies in this review and where studies

did address a component, this was typically done to a “fair”, rather than “good” standard. One

study (4.76%) described a power analysis and two employed blind evaluators (9.52%). Four

studies (19.05%) incorporated adequate controls for parallel treatment completed external to the

research; all at the fair standard. Four (19.05%) involved a comparison to an alternative or well-

described TAU condition and the same proportion evaluated the clinical significance of findings.

Nine (42.86%) specified the assessors’ training or experience with the assessment tool employed,

with eight (38.1%) describing an approach for attrition handling. Whilst nine studies (42.86%)

provided information on the number of therapists involved in the intervention delivery, just one

did this to a good standard and 47.61% of studies provided some information about the

training/experience of therapists. Seven (33.33%) undertook treatment fidelity assessments and

whilst the same proportion examined therapist competence in the delivery of treatment, this was

done to a good standard by one study. Of the seven studies that compared ACT with another

active treatment or TAU, inequity of therapy hours was common, with only one study attaining a

“fair” rating for this item (14.29%). Studies performed better in terms of assessment time points,

with 20 (95.24%) detailing fair-to-good use of reliable outcome measures. Thirteen studies

(61.9%) included at least three rounds of assessment and over 95% of studies (n=20) had fair-to-

good specificity of measures as well as a specified treatment protocol. Finally, 15 studies

(71.43%) provided a fair-to-good description of the participant sample.

Outcomes

Study outcomes are depicted in Table 2. Where data from multiple assessment points was

reported, these are delineated by a backslash (/). While few studies reported effect sizes (ES),

reliable change or clinically significant change indices, these are reported where available. A

narrative synthesis of these results ordered by POMRF rating, from most to least rigorous

methodological category follows.

Well above average

Three studies (14.29%) were rated as well-above average in terms of methodological rigour.

These included two RCTs (L. Hayes, Boyd, & Sewell, 2011; Metzler, Biglan, Noell, Ary, &

Ochs, 2000) and one between-group study (Franklin, Best, Wilson, Loew, & Compton, 2011).

The utility of a behaviour therapy program (including ACT approaches) versus TAU

(psychoeducation) for 339 adolescents with high risk sexualised behaviour was examined in one

study (Metzler et al., 2000). At 3-month follow-up, in contrast to predictions, ACT participants

engaged in greater frequency of sex than TAU participants. At 6-month follow-up, ACT male

participants reported significantly fewer partners than TAU males, but not females. Relative to

TAU, ACT participants reported significantly fewer instances of, and improvements in, sexual

contact with strangers, as well as clinician-rated social competence. Limitations of this study

include low response (18%) and poor retention rate to follow-up assessment time points. The

sample also evidenced significantly higher risk taking behaviours than a random sample of

clients of STD clinics. Whilst this may cast doubt on the representativeness of findings, a

population exhibiting more problematic behaviours might be expected to be increasingly

treatment resistant, which lends further support for ACT. This may also explain the lack of

significant findings at the 3-month follow-up, as it may be that participants required more time to

consolidate therapeutic gains and generalise learnings to a greater number of behaviours. In

contrast to predictions, there were no significant between-group differences in acceptance

measures. However, this study was limited to assessment of acceptance alone and did not

account for the role of other proposed change processes within the ACT hexaflex. It is unclear

from this study the degree of experience of the treating therapists and this too may have impacted

on the findings, as has been identified in other studies (e.g., Franklin et al., 2011). Strengths of

this study include its sizable sample, treatment adherence checks and thorough analysis of

interaction effects. This study attained a POMRF score of 21/44.

In another RCT, 30 depressed adolescents were randomised to TAU (manualised CBT) or

individual ACT (L. Hayes et al., 2011). ACT resulted in significant improvement in depressive

symptoms at posttreatment and 3-month follow-up, findings of small and large effect sizes,

respectively (L. Hayes et al., 2011). Clinically reliable change was observed among 58% of ACT

participants and 36% of TAU participants. ACT achieved greater reductions in depressive

symptoms than TAU at posttreatment and follow-up. At posttreatment and follow-up, 26% and

38% of ACT participants showed reliable clinically significant improvement. Strengths of this

study included the use of trained therapists and psychometrically validated instruments.

Therapists in this research were involved in the delivery of both ACT and TAU interventions,

but a limitation of this study included a lack of information regarding treatment duration, and

treatment fidelity or therapist adherence, preventing examination of contamination of treatment.

This is important as, to draw meaningful conclusions about the effectiveness of treatment,

treatment must be delivered as per protocol (Ost, 2008). The POMRF for this study was 20/44.

Franklin et al. (2011) undertook a trial of habit reversal training (HRT; n=7) versus ACT+HRT

(n=6) among adolescents with chronic tic disorders. Results revealed significant reductions in tic

severity across treatment, with no significant differences between groups. However, in terms of

clinician-rated global impression ratings, superior outcomes were observed for HRT relative to

ACT+HRT in terms of overall percentage improved at each time point (43% vs 40% at week 10;

86% vs 25% at week 14; 57% vs 20% at week 18 and; 71% vs 33% at one-month follow-up).

Likewise, although no statistical comparisons were made on self-rated functioning, a visual

inspection of scores suggested HRT performed somewhat better than ACT+HRT. Strengths of

this study include the use of validated diagnostic instruments, trained assessors who were blind

to treatment allocation and trained therapists. This was the only study included within this

review that compared an ACT protocol with another active alternative treatment and it received

the highest POMRF score in this investigation (25/44). However, a larger sample would have

increased the power to enable further statistical analysis and detect significant effects. All but

one of the therapists involved in this study were relatively inexperienced in ACT and had greater

experience in HRT, which may have implications for treatment quality. In line with this

assertion, the more experienced therapist in this study was found to achieve more substantial

reductions in tic severity scores than did those therapists with minimal experience.

To date, among the child literature, the best evidence for ACT exists for the treatment of tic

disorders, depressive symptoms and high risk sexual behaviour. Taken together these offer

preliminary evidence for ACT in improving both self and clinician-reported outcomes. However,

some improvements were not observable until follow-up, and others observed larger

improvements some months after therapy cessation. ACT was superior to TAU in both studies

that employed these comparisons, which suggests its utility for clinician treating children with

these concerns. While, for chronic tic disorders the addition of ACT to HRT did not produce

additional gains, more experienced ACT clinicians were found to achieve improved outcomes

relative to those with less training. Limited evidence is currently available in the most

methodologically rigorous studies on changes in the ACT core processes.

Above average

Seven studies (33.33%) attained above average ratings on the POMRF. Two examined the

effectiveness of ACT for OCD among three children aged 10-13 years (Armstrong, 2011;

Yardley, 2012). Armstrong (2011) found mean compulsion scores decreased 28.2% on clinician-

rated and 40.4-64.5% on self-reported measures. All participants showed improvement across

measures, with two participants achieving subclinical scores at posttreatment. In line with this,

Yardley (2012) noted all participants showed large improvements across clinician-rated

measures, reflecting an average drop of 47.26%. Self-reported obsessive cognitions in two of

three participants also evidenced improvement. However, both studies are limited in small

sample size, representativeness of the sample, and non-report of control of external treatment or

therapist training. These factors limit the applicability of findings.

The utility of ACT for PTSD/PTS was examined among a mixed sample of community-dwelling

adolescents with PTSD/PTS and adolescent inpatients with PTSD/PTS and a comorbid eating

disorder (Woidneck, Morrison, & Twohig, 2014). Results indicated reductions in the frequency

and intensity of self-rated PTSD/PTS symptoms at posttreatment, reflecting reductions of 63-

69% and 59-81% for the community and inpatient participants, respectively. Similar rates were

found at 3-month follow-up. On clinician-rated measures at posttreatment the average reductions

were 57% and 61% for the community and inpatient participants, respectively, with 71% and

60% at the 3-month follow-up. Avoidance and fusion significantly decreased at posttreatment by

an average of 65% for the community and 57% for the residential participants, with further

reductions at 3-month follow-up. Statistical analysis of QOL outcomes was not reported;

however, visual inspection of raw scores on these measures suggested improved QOL at

posttreatment, with gains maintained or further improved at 3-month follow-up. The small

sample size and the mixed participant sample limits the generalisability of the findings, which

may have impeded a statistical comparison between the residential and community participants.

This is particularly salient as the former were also receiving intensive TAU in the residential

environment for their primary diagnosis of eating disorder. As such, it is difficult to determine

whether TAU may have been diluting the effects of ACT. The therapist was also known to the

residential participants, prior to their commencing ACT treatment and therefore rapport levels

were likely between the groups and this may have impacted on obtained findings. The lack of

independent assessors in this study also may have introduced a degree of bias to the research, as

the therapist also completed all assessments. The resultant POMRF score for this study was

16/44.

An ACT-based group therapy was examined among 28 children presenting with, or at risk for,

emotional dysregulation and externalizing behaviour (Bencuya, 2013). The sample included

children adopted from foster care (n=24), with a lesser proportion (n=4) non-adopted. Forty-two

percent were medicated for psychiatric concerns. At posttreatment, parent-rated measures of

child emotional avoidance, behavior problems, internalizing problems (trend only), and ADHD

symptoms had significantly reduced. Among non-medicated participants, parent-rated child

metacognition deficits decreased and executive functioning was not significantly different.

Among medicated participants, metacognition deficits had increased. Among child-reported

measures there were no significant differences on cognitive emotion regulation or mindfulness at

posttreatment. At follow-up, child-reported cognitive emotion regulation, mindfulness, and

avoidance/fusion significantly improved, relative to pretreatment. Limitations of this study

include the diverse nature of the sample as well as the unequal distribution of participants to

condition. The latter may explain the lack of significant findings between participants in the

waitlist and immediate treatment conditions. This study achieved a POMRF score of 14/44.

Wicksell, Melin, Lekander, and Olsson (2009) compared an ACT-based intervention with TAU

(multidisciplinary plus medication approach) among 30 children with mixed idiopathic pain.

ACT produced significant improvements of small effect size across all primary outcome

measures (pain-related functioning, impairment, interference and health-related QOL) over time

(up to 6 months post). The TAU group also improved across primary outcome measures with the

exception of mental health-related QOL. At posttreatment ACT outperformed TAU on pain

measures and mental health-related QOL. Incorporating all time points, ACT evidenced superior

outcomes to TAU on pain outcomes. Limitations in the current study included a disproportionate

number of sessions across condition (13 ACT versus 22.8 TAU), and the use of outcome

measures with unknown psychometric properties, not validated among young people. The

sample were also highly diverse in terms of clinical presentations, as well as duration of

condition and treatment history, which may have implications for external validity. The

methodological quality of this study was rated as 17/44.

Another study among adolescents experiencing chronic pain observed functional disability and

school absenteeism improved by 63% and 68%, respectively, at posttreatment (Wicksell, Melin,

& Olsson, 2007). Pain intensity and interference were reduced by around 50%. Gains were

maintained at follow-up. Changes were clinically significant for over 70% at posttreatment and

all but one participant at 3-month follow-up. At 6-month follow-up all participants evidenced

clinically significant decreases in pain interference, with 73% for intensity. At posttreatment

there were significant decreases in internalising/catastrophizing, maintained at follow-up.

Caveats of this study include the diverse nature of the sample and the sample size, which limits

the generalisability of findings. Treatment also varied in terms of length and focus with respect

to individual therapeutic goals. Although broadly reflective of clinical practice this lack of

standardisation may have implications for the external validity of findings.

Livheim et al. (2014) detailed two pilot studies, completed over two countries, to examine the

effectiveness of a manualised group ACT program for adolescents with depressive symptoms

(Australian study; N=66) and stress symptoms (Swedish study; N=32). The Swedish study

achieved POMRF rating in the above average range, whereas the Australian study scored in the

below average range. In the Swedish study, participants were randomised to ACT or TAU

individual counselling with the school nurse. At posttreatment a large significant improvement

was observed in self-reported perceived stress in favour of ACT, with no change for TAU. No

significant differences were observed in self-reported QOL, depression, stress, anxiety

(marginally significant improvement relative to TAU) or general mental health. Change in

avoidance and fusion was non-significant, with change in mindfulness marginally significant for

ACT relative to TAU. Greater session attendance was associated with significantly higher QOL

ratings and improved depression and stress ratings. Limitations specific to this study included

that the TAU intervention was completed in individual, not group format, and was not

administered to all participants or in a consistent fashion. This inequity in the comparison makes

it difficult to delineate the impact of factors such as the delivery format or therapeutic hours in

contributing to the outcome. Whilst this study reported a power analysis, the number of

participants was less than anticipated and as a consequence, it was underpowered. Thus, it is

possible that significant effects that may have been present were not detected. This study attained

a POMRF of 14/44.

Taken together, studies with above average methodological rigour showed ACT to be effective

in achieving reductions in clinical and self-rated OCD, pain symptoms, and PTS/PTSD, at

posttreatment and follow-up. Pain and OCD outcomes were consistent across two studies.

Among children experiencing or at risk for emotional dysregulation ACT was also effective in

improving the majority of parent-rated measures at post and follow-up. However changes in

child-ratings were not apparent until follow-up. Mixed findings were observed for the

effectiveness of ACT among children with stress. However this study was also underpowered,

which may have impacted on findings. QOL outcomes were examined in one study on pain and

one on stress. The former found significant changes over time and relative to TAU for ACT, in

the latter changes were non-significant. Concerning ACT process measures, avoidance and

fusion significantly reduced among children with PTS/PTSD as well as those experiencing or at

risk for emotional dysregulation.

Below average

In accordance with POMRF ratings, eight (38.1%) studies scored below average. The utility of

ACT as a treatment for trichotillomania was examined in a case series of two adolescents (Fine

et al., 2012). While both participants evidenced decreases in focused and automatic hair pulling

over the course of 11 treatment sessions, methodological caveats included a lack of therapist

training information, checks for treatment adherence/therapist competence and an absence of a

follow-up assessment. As a case study it also lacked a control group and random allocation to

treatment, it attained a POMRF rating of 8/44.

The second of the pilot studies described by Livheim et al. (2014) was completed with Australian

adolescents with depressive symptoms (N=66). This study employed a planned comparison,

where girls were randomised to ACT or TAU (12-weeks monitoring by school counsellor), and a

single boys group (N=8) received ACT. Significant improvements of large effect size in self-

reported depression overall were observed among ACT participants, with no changes for TAU,

at posttreatment. Effects favoured ACT across the dysphoric mood, anhedonia/negative affect

and negative self-evaluation symptoms, with moderate to large effect sizes. No significant

changes were observed on somatic symptoms. Changes in acceptance and defusion were only

marginally significant for ACT relative to TAU. Caveats included the non-measurement of

participant session attendance, which affects measurement bias. Pretreatment differences in

overall depression scores were observed and thus an alternative interpretation of effects may be

that changes reflected a regression to the mean (i.e., if a variable is extreme on its first

measurement, it will tend to be closer to the average on its second measurement). Other

limitations of this study included the sole reliance on self-report measures, which are impacted

by social desirability. The vast majority of participants were female, which impacts on the

capacity to generalize the result to male populations. Follow-up assessment was not included to

examine the durability of observed outcomes. This is important as other studies with children

have found that the effects of ACT are not immediately observable at posttreatment. Finally

therapist competence and adherence to the protocol were not examined. Given the therapists

were relatively inexperienced in the use of ACT this is an important consideration in determining

whether the program was ACT consistent.

In a study on chronic pain and ACT, 20 children evidencing moderate functional disability from

chronic pain were allocated to ACT (N=10) or to an undefined control condition (N=10)

(Ghomian & Shairi, 2014). Both child and parent reports in the ACT group evidenced significant

changes in overall functional disability as well as the capacity to perform physical and daily

activities. There were no significant changes for controls. Parent reports indicated ACT

outperformed control across outcomes at posttreatment and 1.5 month follow-up. Relative to

pretreatment, at 3 month follow-up parent reports indicated significant differences in favour of

ACT, relative to control, on both routine and total functional disability. Gains were maintained

between posttreatment and follow-up. On child-reported physical disability there were no

significant differences between ACT and control across time, in contrast to parent-reported

outcomes. However, the quality of this study is weakened by its reliance on one outcome

measure. Furthermore, the limited detail on the treatment protocol in makes it difficult to

determine the methodological rigour of the research (e.g., whether the treatment was delivered in

individual or group format, etc.), reflected in its POMRF score of 10/44.

Another study on pain involved a three week group-based interdisciplinary residential program

with 98 adolescents (Gauntlett-Gilbert, Connell, Clinch, & McCracken, 2013). The program

consisted of physical conditioning, activity management, and ACT approaches. Results showed

improvements at posttreatment, of small to medium effect sizes, in school attendance,

medication and health care usage, acceptance, pain anxiety, depression, catastrophizing,

social/physical functioning, development, and objective physical measures. Pain intensity did not

change, in contrast to the observations of Wicksell et al. (2007). At follow-up, all measures

significantly improved except pain intensity, depression, and development. Increased acceptance

was related to improved physical and social functioning, objective physical measures, and all

psychological variables. There are several limitations of this study, reflected by its POMRF score

(11/44). The lack of a control group and the use of an interdisciplinary multicomponent approach

may confound the extent to which changes in measures can be attributed to ACT. This may also

explain the differences in pain intensity to that of Wicksell et al. (2007). However, as stated by

the authors, results were consistent with the ACT model, in that changes occurred in functioning,

in the absence of similar reductions in pain outcomes (Gauntlett-Gilbert et al., 2013). Other

caveats include the lack of treatment adherence or fidelity evaluations and difficulties of

generalizing the results from intensive residential treatment to other settings. Furthermore, this

study examined associations between changes in one ACT process measure, acceptance, and

other outcomes, and did not examine the remaining ACT hexaflex processes, despite their

inclusion in treatment. As a consequence it is unclear how these might be differentially related to

changes in other measures.

Heffner, Sperry, Eifert, and Detweiler (2002) examined ACT in the treatment of a 15 year old

with anorexia nervosa. Results showed ACT produced movement from the clinical to nonclinical

range at treatment cessation on drive for thinness and ineffectiveness outcomes. However, a

body dissatisfaction measure, remained within the clinical range. The participant’s weight fell

within the normal range at follow-up, and typical menstruation resumed. The methodological

quality of this study was below average (9/44), reflective of the case design and ensuing

limitations as well as lack of treatment adherence checks.

A group-based ACT protocol was examined in a group of seven adolescents with Asperger’s

Syndrome and/or non-verbal learning disability (Cook, 2008). At posttreatment significant

improvements in valued living were observed, but changes in avoidance and fusion were

nonsignificant. Correlations between change scores on avoidance/fusion and obsessive-

compulsive, interpersonal sensitivity, depression, anxiety, hostility, paranoid ideation, and

psychoticism measures were observed (Cook, 2008). Limitations of this study include the small

sample, the absence of control comparison, sole reliance on self-report measures and a lack of

statistical analysis of changes. The level of experience of the graduate student facilitator with

ACT was unclear and treatment fidelity/adherence checks were not in place to ensure

consistency with the protocol. This study scored 12/44.

Another study examined the utility of an acceptance and mindfulness “self-control training”

intervention for three children with ADHD (Seibert, 2011). Following baseline stabilization,

associated with time tolerated before eating a preferred food, all participants underwent five

sessions of self-control training. This involved learning acceptance and mindfulness skills in

response to impulsive thoughts and bodily sensations evoked in the desire to eat a preferred food.

At the conclusion of each of the five sessions, participants had access to a preferred food after a

delay period of 10 times their baseline time. As predicted, all participants were able to tolerate a

greater delay after self-control training and could meet the 10 times time requirement for self-

control training for the majority of training sessions. Two of three participants met this for 100%

of self-control training trials, and the third participant for all but one trial. Two of three

participants tolerated three times their natural baseline delay to receive a large portion of their

preferred food. One participant continued to be unable to tolerate this delay. Limitations of this

study included the small sample, lack of control group, absence of reliability checks of diagnoses

and therapist competence. Treatment involved only two of the six ACT core processes, which

limits conclusions about the utility of ACT more broadly. In line with these caveats, this study

received 12/44 on the POMRF.

In another study, 15 adolescents with high self-reported problem behaviours completed a

program that included three core processes of the ACT hexaflex; values, cognitive defusion and

self-as-context (Luciano et al., 2011). The study trialled a values intervention with either

defusion (Defusion I) or defusion + self-as-context approaches (Defusion II). On the basis of the

number of endorsed problem behaviours, participants were classified as high (score 6) or low

risk (scores 5). Half of the low-risk participants received Defusion I. The remaining half of the

low-risk, and all high-risk participants, received Defusion II. All participants received the values-

orientated session. There were significant changes in problem behaviours and differences

between groups subsequent to the values-orientated session. For Defusion I no significant

differences were observed for measures of problem behaviour, experiential avoidance/fusion or

acceptance across time. Low-risk participants in Defusion II evidenced significant changes

across all measures with results maintained at follow-up. Four of five participants reported no

problem behaviour at post and maintained this at follow-up. Results for high risk participants

were equivalent, with two exceptions; experiential avoidance/fusion did not change over time,

and improvements in acceptance at post were not maintained at follow-up. A comparison among

low risk participants across defusion conditions revealed consistently significantly superior

results for Defusion II. The authors concluded that defusion was bolstered by the inclusion of

self-as-context approaches. The lack of changes in avoidance/fusion among high risk participants

was unexpected. It is possible that the intervention was of insufficient duration to evidence

changes on this measure among participants with more severe behavioural problems. This study

was limited by the overall numbers in each group, and use of only three of the six core ACT

processes. Given the low number of studies in this category and the low sample sizes used, this

study scored 12/44. Further studies to examine the comparative effectiveness of ACT are

warranted.

Studies scoring one standard deviation below the mean POMRF rating for methodological rigour

found that ACT was effective in reducing the majority of self-reported clinical outcomes among

participants with trichotillomania, depression, pain (two studies), anorexia, ADHD, and problem

behaviour. Results were also consistent on parent-report in one study of children with pain

conditions. Where ACT was compared with TAU, ACT achieved favourable clinical outcomes

among participants with depression and pain, across time. With respect to process measures,

changes in avoidance and fusion were mixed. Improvements were found among children who

endorsed five or less problem behaviours, but not among those with six or more, and non-

significant changes were observed among adolescents with Asperger’s Syndrome. Acceptance

improved among participants in one study of children with pain conditions and among those with

problem behaviours. Significant improvements in valued living were observed among children

with Asperger’s Syndrome.

Well below average

Three studies (14.29%), all case studies, scored well below average on the POMRF. By their

very nature, case-studies are limited in their ability to determine whether change observed was

greater than chance alone. Their sample size also makes generalisation of the findings difficult.

However, these studies make an important contribution to the field in that it supports the clinical-

research community by providing data on a population for which there is a dearth of research.

Disorder and treatment-tailored studies such as those explored in these case studies and the

ability to draw conclusions from research conducted in naturalistic settings is often not possible

in large efficacy studies, thus case-studies are often a necessary precursor to appropriately

designed larger-scale trials.

A study of ACT for a 14-year-old female with idiopathic pain found reductions in functional

disability, pain and emotional-focused avoidance at posttreatment (Wicksell, Dahl, Magnusson,

& Olsson, 2005). Improved school attendance and achievement of values-based goals was also

observed with results maintained at follow-up. This study received a 7/44 POMRF rating, a

reflection of its case study nature, lack of treatment adherence and competence checks, and

reports of clinical significance.

Brown and Hooper (2009) examined ACT in the treatment of anxiety in an 18 year old female

with a moderate-to-severe learning disorder and school refusal. Experiential avoidance had

reduced at posttherapy. The participant was increasingly calm and socially confident, and had

recommenced school in accordance with anecdotal parent-report. Gains were maintained at

follow-up. However, several caveats limit the generalisability of findings, reflected in its

POMRF score of 3/44, the lowest of all studies included within this review. One

psychometrically evaluated assessment tool was employed, focused on ACT processes of

change, and this study relied on anecdotal evidence to determine the impact of treatment on the

clinical outcome of anxiety severity. The intervention was markedly different from protocol, as

therapeutic adjustment were made throughout and the program extended extending beyond the

proposed 10 session to a 17 session intervention.

A family-based ACT intervention was completed with a 16 year old male with sickle cell disease

(SCD) who experienced pain, fatigue, social apprehension and adaptive behaviour deficits in

studying, socialisation and inattentiveness/inaction (Masuda, Cohen, Wicksell, Kemani, &

Johnson, 2011). No significant self-reported changes in social anxiety or QOL were observed at

posttreatment, although scores remained in the normal range relative to a comparative sample of

SCD children. However, at follow-up, social anxiety and QOL scores improved to one standard-

deviation below and above, respectively, the average in the comparison sample. Pain reports

remained unchanged over time. Parent-report indicated improvements academic performance

and functioning. Scores on avoidance/fusion were greater than the comparison sample at pre and

posttreatment, however, large reductions were observed at 3-month follow-up. The case study

nature of this study, lack of report of assessor training and treatment adherence/fidelity, are

reflected in its POMRF score of 7/44.

In summary, two of these studies examined changes in clinical outcomes, with both observing

improvements in self and parent reported outcomes. These studies showed some support for the

processes of committed action, via the achievement of values-based goals, as well as

improvements in avoidance and fusion at either post or follow-up. As described above, these

studies should be interpreted with caution, given their methodological limitations. However,

clinicians working with children exhibiting less prevalent conditions such as SCD or those

working in disability settings may glean some utility from these findings for their populations.

Discussion

The past few years has seen a proliferation of ACT research in the treatment of conditions among

children. While there are two existing reviews of the literature, the present investigation is the

first to be conducted systematically. It involved both the published literature as well as

unpublished theses/doctoral dissertations and specifically targeted studies involving treatment for

children, rather than parent-based interventions. It also expands upon the findings of earlier

reviews through an update of the literature completed over the past few years and the inclusion

of a greater number of intervention-specific studies.

Twenty-one eligible studies were identified involving treatment for a spectrum of presenting

issues. While the literature is still in its infancy, and subject to several methodological quality

issues, the evidence available to date suggests that ACT produces significant improvements in

the majority of self and clinician-reported clinical outcomes across presenting problems. While

few studies incorporated parent-reported outcomes, where these were used, they were broadly

consistent with child and clinician-rated outcomes. These findings support the argument of

several researchers (e.g., Coyne et al., 2011; Greco et al., 2005; Hadlandsmyth et al., 2013) who

suggest that ACT is a viable therapeutic approach for clinicians working with child populations.

These outcomes also support the assertion that ACT has potential utility as a transdiagnostic

approach (S. C. Hayes et al., 2012; Livheim et al., 2014), an area for future research in larger,

methodologically rigorous trials with multiple clinical presentations.

There remains a relative dearth of comparisons of ACT to other active treatments. Just one study

included within this review, compared ACT to another active treatment, and found the addition

of ACT to another active treatment did not achieve more favourable outcomes (Franklin et al.,

2011). However, a key limitation in this study is that clinicians were relatively inexperienced in

the use of ACT, and expertise was associated with improved outcome (Franklin et al., 2011).

ACT can be rather counterintuitive for unfamiliar clinicians and it involves several experiential

exercises/metaphors that are abstract in nature. Arguably, this difficulty is intensified when

delivered to adolescents, a population who may exhibit a greater spectrum of

cognitive/development differences. Taken together, these findings implore the importance of

skill and competence in the use of ACT prior to attempting this approach with clients for optimal

outcomes.

More research is clearly warranted to establish whether ACT works better than alternative

approaches. Despite this limitation, those studies comparing ACT to TAU found ACT evidenced

superior outcomes among children with issues of pain, depression and sexualised behaviour. This

suggests ACT should be considered by clinicians working with children with these presenting

concerns and may achieve more optimal outcomes that typical treatments. Several studies found

that treatment gains were either not fully evident at posttreatment (or initial follow-up) or that

greater improvements for ACT were obtained some months after therapy cessation (e.g., L.

Hayes et al., 2011; Metzler et al., 2000; Wicksell et al., 2007). Thus the inclusion of follow-up

time points is an important consideration for future research.

Few presenting problems have been investigated among children by more than one or two

studies, and this is also important for future research to consolidate the evidence base. At this

stage the most widely researched condition is pain, with studies consistently observing that ACT

results in improvements in functional disability and interference. Although studies differed in

methodological rigor, outcomes were consistent in this area. Thus, there is encouraging support

for clinicians to employ ACT approaches with young people presenting with pain concerns.

However, as the majority of these studies were conducted by a group of affiliated researchers

possible author bias cannot be ruled out. As such, it is recommended other researchers in

different settings test and replicate these findings. This links in with the concept of therapist

allegiance, which potentially affects outcomes in psychotherapy research. For instance,

allegiance bias may occur with study results being contaminated or distorted by the

investigators’ preferences towards a treatment or theory (Luborsky, Singer, & Luborsky, 1975).

In a meta meta-analysis of 30 meta-analyses (Munder, Brutsch, Leonhart, Gerger, & Barth,

2013) it was concluded that the researcher alliance outcome association is substantial and robust.

For example, a researcher’s enthusiasm towards a therapy might result in superior training and

supervision of the therapists implementing that treatment, as opposed to a less preferred

comparative treatment. It is also possible that greater experience and skill in a preferred

treatment could, however inadvertently, result in better performance of this treatment over a non-

preferred intervention. Thus the importance of reporting allegiances and considering the potential

for such bias to occur should be addressed in future research.

Despite the focus of ACT on QOL outcomes, few studies included within this review examined

changes in QOL specific measures. Thus, the research base is currently limited in the ability to

draw meaningful conclusion on the impact of therapeutic changes on children’s day-to-day

living. Future research should augment clinical outcomes with those specific to QOL, which

have been argued to reflect the clinical significance of changes (Gladis, Gosch, Dishuk, & Crits-

Christoph, 1999; Kazdin, 1977; Safren, Heimberg, Brown, & Holle, 1996). Studies that did

employ these measures all found improvements over time, with the exception of the study on

stress (Livheim et al., 2014), which was underpowered to detect effects. In line with findings on

clinical outcomes, the latter study observed superior outcomes among ACT participants, relative

to TAU. Taken together, these findings offer preliminary evidence for the utility of ACT in

improving both clinical and QOL outcomes among children.

Limited evidence is currently available on changes in the ACT core processes among children,

particularly in the most methodologically rigorous studies, and the evidence available is mixed.

Avoidance and fusion was the most commonly investigated process. Among eight studies 50%

indicated improvements at post or follow-up. Others observed a nonsignificant positive trend

(Cook, 2008), found improvements were limited to presentations of lower severity (Luciano et

al., 2011) or saw no improvements (Livheim et al., 2014). Positive changes were observed in

acceptance across two studies, but not in a third, which was underpowered to detect effects.

Evidence for valued living and committed action was limited to one or two studies, with positive

improvements observed among participants treated with ACT. Investigation of the ACT core

processes is important due to their hypothesised role in increasing psychological flexibility.

Increased research effort in this domain is likely to support knowledge development into

processes through which ACT fosters positive outcomes, typically termed “the mechanisms of

change” (Ciarrochi, Bilich, & Godsell, 2010; Kazdin, 2007; Kraemar, Wilson, Fairburn, &

Agras, 2002). This in turn is likely to foster parsimonious clinical practice, optimising clinician-

patient encounters to facilitate shorter term interventions delivered with improved sensitivity and

specificity (Kazdin, 2007; Kraemar et al., 2002).

Overall methodological quality assessment identified a number of strengths among eligible

studies. Most employed sufficiently detailed treatment protocols as to allow for replication,

assessment of outcome was examined at follow-up time points, and most utilised specific

outcome measures that were also valid and reliable. Future research should continue to adhere to

these practices. However, several caveats were identified and should be addressed in ongoing

studies, including heterogeneity in treatment duration between groups and a lack of consideration

for the clinical significance of findings. Most studies did not report therapist training, checks for

treatment adherence or therapist competence. An effect size calculation was not possible in many

studies due to the methodological limitations such as low sample size. A comparison of average

POMRF ratings in the current investigation (M=13.29), relative to a recent review of ACT for

anxiety with predominantly adult studies (M=17.29; Swain et al., 2013) also suggests the

methodological quality of studies involving child samples presently lags behind that of the adult

literature. In explanation for this finding, there was a predominance of small heterogeneous

samples, few conditions were investigated by more than one study, and designs that typically

lacked control or alternative treatment comparisons, limiting conclusions. However, such studies

may offer greater validity for clinicians working in real-world contexts than randomised efficacy

trials due to the employment of naturalistic settings and multiple baseline measures. Thus the

contribution of case studies or those in naturalistic settings to the scientific body of knowledge

should not be disregarded, especially for clinicians working with children from low prevalence

clinical populations.

Areas needing investigating in future research include an examination of the role of demographic

factors in outcomes, as several studies found outcomes varied by factors such as gender and race,

and others still observed medication status was associated with divergent results. The expansion

of studies to children of different age groups and those experiencing comorbid problems, is also

indicated. Clinicians should note that there is currently a dearth of evidence for ACT among

children under 12 years and in ACT treatment delivered in group or family-based formats. In

many studies the ACT intervention employed was delivered as a component of a broader

intervention and thus it is difficult to determine the contribution of non-ACT therapeutic

components to outcomes. Findings must be replicated and examined relative to control

conditions as well as active treatment alternatives. For the majority of disorders/conditions

specific effectiveness is currently limited to one or two studies. Taken together, these findings

suggest such additional methodologically stringent research is warranted taking these observed

pitfalls into consideration. Despite the methodological inadequacies identified in the research

reviewed, it is encouraging to see the rate at which ACT research in children is increasing, as is

the scientific rigour.

Conclusion

Emerging research of ACT in the treatment of children is encouraging for the utility of this

therapeutic approach for clinicians working with young people. To consolidate and build upon

this preliminary evidence, larger methodologically rigorous trials are required across a broader

spectrum of presenting problems and particularly among younger children. As difficulties in

childhood can result in substantial impairment across various life domains, it is important that

appropriate, evidence-based, treatment is available. It is hoped that the results of this review will

support the conduct of future research in this area with increased methodological rigour, to

provide additional data on the utility of ACT as a viable intervention available to clinicians in the

treatment of problems among children.

References

AACAP. (2007). Practice parameter for the assessment and treatment of children and adolescents with

anxiety disorders. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 46, 267-

283.

AACAP. (2012). Practice parameter for the assessment and treatment of children and adolescents with

Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent

Psychiatry, 51, 98 -113.

Arch, J. J., & Craske, M. G. (2008). Acceptance and commitment therapy and cognitive behavioral

therapy for anxiety disorders: Different treatments, similar mechanisms? Clinical Psychology:

Science and practice, 15, 263-279.

Armstrong, A. B. (2011). Acceptance and commitment therapy for adolescent obsessive-compulsive

disorder. Unpublished doctoral dissertation, Utah State University.

Bencuya, N. L. (2013). Acceptance and mindfulness treatment for children adopted from foster care.

(Unpublished doctoral dissertation), The University of California.

Blackledge, J. T., Ciarrochi, J., & Deane, F. (2009). Acceptance and Commitment Therapy :

Contemporary Theory, Research and Practice. Brisbane, QLD: Australian Academic Press.

Brown, F. J., & Hooper, S. (2009). Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT) with a learning disabled

young person experiencing anxious and obsessive thoughts. Journal of Intellectual Disabilities,

13, 195-201.

Burke, C. A. (2010). Mindfulness-based approaches with children and adolescents: A preliminary review

of current research in an emergent field. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 19, 133-144

Chawla, N., & Ostafin, B. (2007). Experiential avoidance as a functional dimensional approach to

psychopathology: An empirical review. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 63, 871-890.

Ciarrochi, J., Bilich, L., & Godsell, C. (2010). Psychological flexibility as a mechanism of change in

acceptance and commitment therapy. In R. Baer (Ed.), Assessing Mindfulness and Acceptance:

Illuminating the Processes of Change. Oakland, CA: New Harbinger Publications, Inc.

Cook, S. (2008). Can you act with aspergers: A pilot study of the efficacy of acceptance and commitment

therapy (ACT) for adolescents with asperger syndrome and/or nonverbal learning disability.

(Unpublished doctoral dissertation), Wright Institute Graduate School of Psychology.

Coyne, L. W., McHugh, L., & Martinez, E. R. (2011). Acceptance and commitment therapy (ACT):

Advances and applications with children, adolescents, and families. Child and Adolescent

Psychiatric Clinics of North America, 20, 379-399.

Creswell, C., Waite, P., & Cooper, P. (2014). Assessment and management of anxiety disorders in

children and adolescents. Archives of Disease in Childhood, 99, 674-678.

Farchione, T. J., Fairholme, C. P., Ellard, K. K., Boisseau, C. L., Thompson-Hollands, J., Carl, J. R., . . .

Barlow, D. H. (2012). Unified protocol for transdiagnostic treatment of emotional disorders: A

randomized controlled trial. Behavior Therapy, 43, 666-678.

Fine, K. M., Walther, M. R., Joseph, J. M., Robinson, J., Ricketts, E. J., Bowe, W. E., & Woods, D. W.

(2012). Acceptance-enhanced behavior therapy for trichotillomania in adolescents. Cognitive and

Behavioral Practice, 19, 463-471.

Franklin, M. E., Best, S. H., Wilson, M. A., Loew, B., & Compton, S. N. (2011). Habit reversal training

and acceptance and commitment therapy for tourette syndrome: A pilot project. Journal of

Developmental and Physical Disabilities, 23, 49-60.

Gaudiano, B. A. (2009). Ost's (2008) methodological comparison of clinical trials of Acceptance and

Commitment Therapy versus Cognitive Behavior Therapy: Matching apples with oranges.

Behaviour Research & Therapy, 47, 1066-1070.

Gauntlett-Gilbert, J., Connell, H., Clinch, J., & McCracken, L. M. (2013). Acceptance and values-based

treatment of adolescents with chronic pain: Outcomes and their relationship to acceptance.

Journal of Pediatric Psychology, 38, 72-81.

Ghomian, S., & Shairi, M. R. (2014). The effectiveness of Acceptance and Commitment Therapy for

children with chronic pain on the function of 7 to 12 year-old. International Journal of

Pediatrics, 2, 195-203.

Gladis, M. M., Gosch, E. A., Dishuk, N. M., & Crits-Christoph, P. (1999). Quality of life: Expanding the

scope of clinical significance. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 67, 320-331.

Greco, L. A., Blackledge, J. T., Coyne, L. W., & Ehrenreich, J. (2005). Integrating acceptance and

mindfulness into treatments for child and adolescent anxiety disorders: Acceptance and

commitment therapy as an example. New York: USA: Springer.

Hadlandsmyth, K., White, K. S., Nesin, A. E., & Greco, L. A. (2013). Proposing an Acceptance and