This article was featured in One Great Story, New York’s reading recommendation newsletter. Sign up here to get it nightly.

In the middle of the night, Angie McCoy flipped onto her stomach in bed and felt something hard in her right breast. It was July 2020, and she and her husband, Tim, were staying at a rental house in Texas Hill Country while they waited for the construction of their new home to be finished. She didn’t know how to describe the sensation — it wasn’t quite a lump, but something about it felt off. It was most pronounced when she lay against a firm surface.

The next day, McCoy made an appointment with a general practitioner, who referred her for a mammogram and an ultrasound. The radiologist told her that both of those scans were negative — he couldn’t see anything that indicated cancer. “I think we’re just dealing with dense breast tissue,” he said, adding that she should come back in six months for retesting just to be sure. Dense breast tissue. This was nothing new: Radiologists had always mentioned that McCoy had dense breasts, but she didn’t understand what it meant or why she should care. None of her doctors had ever said this might be cause for concern.

Six months later, in February, she had another mammogram and ultrasound. The doctors, again, said that both were negative. But the hardness in her breast was still there. McCoy ran through possible explanations in her head: At 52, she was perimenopausal, so her breasts would often hurt and were sometimes swollen. Besides, she trusted doctors — her own late father was a radiologist.

By the summer of 2021, the hardness had begun to feel like a ridge at the bottom of her breast. One day in July, McCoy was reading a book on her front porch when an excruciating pain began to radiate from her right armpit down past her elbow. That night in bed, she was awoken by a sudden pain unlike anything she’d experienced before. She looked down and saw that her right breast was severely inflamed. McCoy stood up, walked over to her bathroom mirror, and lifted her pajamas. What she saw astounded her: That breast was cartoonishly large, nearly double the size of the left. It was so remarkable that “for the first time ever in my life, and probably the last,” she took a photo of herself naked. Days later, she showed the image to her primary-care provider. The doctor dismissed it as nothing serious but ordered yet another mammogram and ultrasound.

In This Issue

Two weeks later, McCoy was back at the radiologist’s office. “Good news!” he declared. “Both scans are negative.” He asked her to show him what was bothering her. “Can you feel this deep ridge?” she asked. “Do you see how inflamed the right breast is?” Yes, he could feel it, but he could see nothing concerning on the mammogram. He told her that if she wanted to be absolutely certain, she could get a biopsy. Also, he said, if anything changes, she could schedule another appointment.

McCoy walked out into the parking lot and stood there in anger. If anything changes? She was an obedient person and had always listened to doctors, but it had been a year since she first felt that odd hardness in her right breast. To her, all of the changes that had taken place in her body since then signaled something distinct and alarming. Later that day, she called her primary-care doctor and requested to see a specialist. She received an appointment for six weeks later with a breast surgeon who she was told could order more tests.

The summer dragged on. Her breasts grew increasingly sore, aching daily. During Pilates class, she’d be lying face down on a box atop the reformer machine and feel the mass, firm as an unripe avocado. When she finally had her biopsy in early September, the skin of her right breast was so taut that the nipple was retracted. The biopsy was followed by an MRI. McCoy was walking the three-mile loop in her neighborhood the next day when she got the call from the surgeon: metastatic breast cancer. “It looks like there are multiple highly suspicious metastatic lesions in your sternum, ribs, and clavicle,” the surgeon said. It was a hot, dry afternoon. She hung up and stared down at her phone.

Two weeks later, McCoy got her first PET scan, a sensitive imaging test that doctors use to determine how far cancer has spread in organs and tissues. It confirmed that McCoy had cancer in all of her bones. “Nose to knees,” she was told. “Innumerable lesions.” The PET scan resembled one of Jackson Pollock’s canvases, like someone had splattered paint all over her skeleton. It had metastasized so far that the kinds of treatment available for earlier-stage breast cancer — a lumpectomy, a mastectomy — were no longer an option.

McCoy thought back on her years of compliance with doctors, on her near decade of yearly mammograms with never an abnormal result. “I had done everything right. I’ve done everything I was supposed to do,” she says. “It was devastating knowing that the cancer was growing the entire time.”

Get your mammogram! is a directive that all American women hear from an early age. This is due, in part, to one of the most effective public-health campaigns in medical history. The first instances of mammography produced images of unreliable or varying quality, but in the late 1950s, a Houston radiologist named Robert Egan standardized a new technique that not only yielded clear, reproducible scans but also dependably picked up cancers that physical exams had missed or that appeared in women with no symptoms. In the mid-1960s, using Egan’s method, a team of radiologists in a van outfitted with X-ray machines parked beside ice-cream trucks in midtown Manhattan and screened 62,000 women on their lunch breaks.

Over the next four decades, mammograms would become the gold standard for breast-cancer detection. In the early 1980s, the American Cancer Society began recommending mammograms every one to two years for women over the age of 40, a recommendation it would update to yearly in 1997. Expanded media coverage, screening programs, and campaigns like the global “Turn your city pink!” initiative — often sponsored by mammography-makers like Siemens — encouraged women over the age of 40 to seek regular mammograms for early detection of breast cancer. Today, yearly mammograms are covered by most major health-insurance plans, as well as by Medicaid, for women 40 and older. Walmart has even begun rolling out a pilot program in which people can get their yearly mammogram in-store.

Mammograms have decreased the mortality from breast cancer by 40 percent since 1990. But in early studies of Egan’s technique, more than one in five women received a false-negative result in which mammograms failed to detect cancer entirely. And even as the technology advanced — as companies like DuPont introduced screen-film and digital mammography, which make the imaging process both faster and higher contrast, and 3-D mammograms that take images from multiple angles — the problem of missed cancers has remained.

Since the aughts, experts in the breast-imaging and breast-surgery world have identified one factor that can make it more difficult for a mammogram to detect cancer: breast density. The breast is made up of three kinds of tissue: glandular tissue, which includes the lobules that produce milk; fibrous connective tissue, which includes the ducts that deliver the milk to the nipples; and fatty tissue, which fills the space in between. When a breast contains more glandular and connective tissue than fatty, it’s classified as dense.

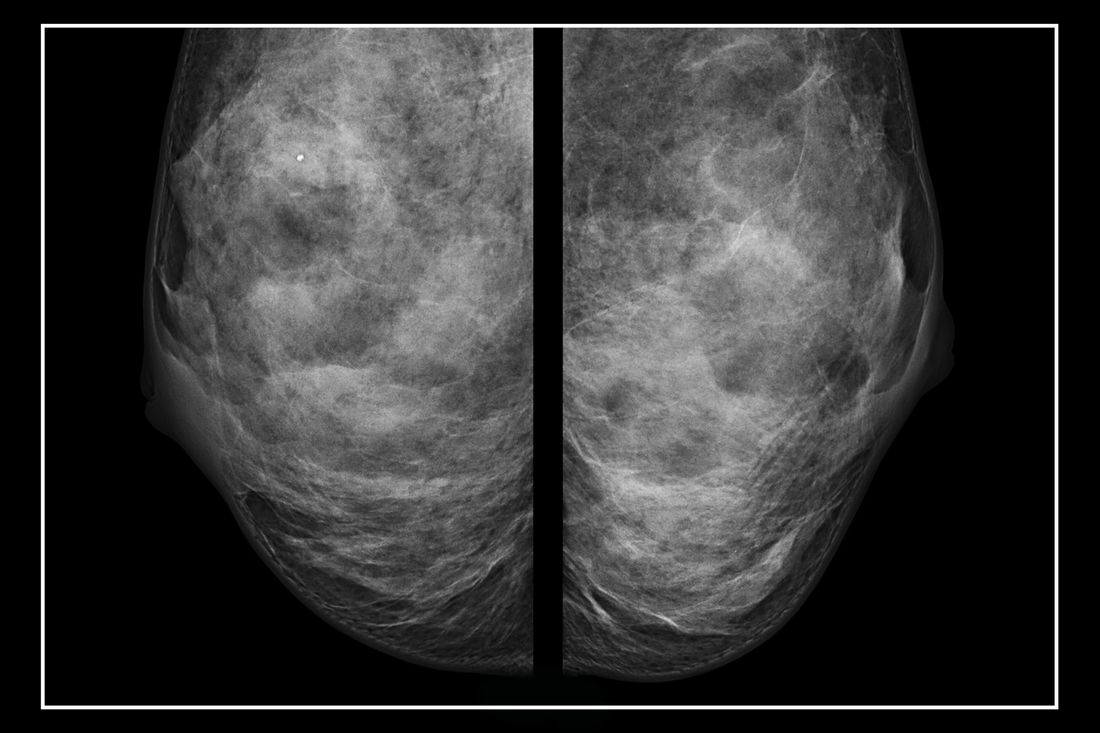

On a mammogram, fatty tissue appears as dark gray or black. Cancer tissue, which shows up as white, should stand out in stark relief. But dense breast tissue also shows up as white and can completely obscure a malignant white mass. Elisa Port, the chief of breast surgery for the Mount Sinai Health System in New York, has compared finding cancer in a dense breast on a mammogram to spotting a polar bear in a snowstorm. “White on white is difficult to see against the background,” she says. In a fatty breast, mammograms are up to 98 percent accurate; in an extremely dense breast, the accuracy can be as low as 30 percent. Sometimes a woman with dense breasts might supplement her mammogram with an ultrasound. “That’s an easy test to do, but everyone has this misconception that an ultrasound is going to close the gap entirely,” Port says. “An ultrasound will only pick up about one or 2 percent extra of cancers.” This is hardly a fringe problem. Half of women in the U.S. have dense breasts, and, difficulties of detection aside, women with dense breast tissue are also at higher risk for developing cancer, though clinicians aren’t sure why.

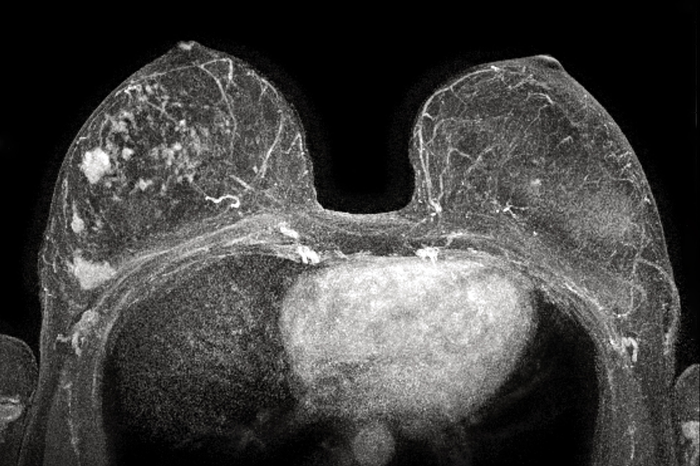

“We know what the best screening method would be, but we fail to use it,” says Christiane Kuhl, who serves as chair of radiology at RWTH Aachen University Hospital in Germany. According to Kuhl, it has been uncontroversial among radiologists and other experts for decades that the most sensitive tool for early detection of breast cancer is the MRI. During a breast MRI, a patient lies face down with arms either overhead or by their sides and enters the MRI machine, which uses a large magnet, radio waves, and a computer to produce sharp, detailed images of far higher contrast resolution than mammograms. Back in 2007, Kuhl published a study in The Lancet that examined the results of cancer screens for more than 7,000 women and found that mammograms missed 48 percent of ductal carcinoma in situ (the earliest form of breast cancer), while MRIs missed 2 percent. And in dense tissue, tumors and masses will show up on a breast MRI as distinctly white against a black background.

Organizations like DENSE (Density Education National Survivors’ Effort) have been trying over the past decade to raise awareness about breast density and the additional problem it poses in mammograms, and as of last year, 38 states had enacted laws that require medical centers to send letters to women informing them if they have dense breasts. (In 2023, the FDA made this practice a national policy, and the remaining 12 states have until September 2024 to implement it.) Still, even when women are notified, rarely are they warned about its implications or given instructions to pursue further testing. Hospitals, primary-care doctors, and OB/GYNs have not changed their protocols when screening women with dense breasts. Usually, the burden rests on the patient.

When she was 34, Katy Weade, a life and health coach in Illinois, began getting regular mammograms after discovering a benign cyst in her breast. But Weade has dense breast tissue, and it was only upon getting an MRI at age 41 that she learned she had stage-three breast cancer. It had spread to her lymph nodes. She posted a video about the experience on Instagram, and one day she received a DM from a stranger who had seen her post. Despite years of clean mammograms, the woman had recently found a rocky lump in her breast and was inspired by Weade to request additional screening. “I’m praying for you that it turns out to be nothing. Please keep me posted!” Weade wrote back.

“Thank you, I just left a message for my doctor with the nurse’s station,” the woman replied. Two weeks later, she sent Weade a photograph of a piece of paper. It was the results of her additional tests, and on it was written “Invasive carcinoma with mucinous features. Large tumor but still considered Grade 1.”

Many patients have to demonstrate extreme tenacity in order to persuade their doctors to order supplemental testing. In August 2022, Tina Paxton, a teacher in Texas, experienced pain so severe in her right breast that it would “send me to my knees.” Her doctor was convinced she had only pulled a muscle running, and for months he told her to up her dosage of Excedrin.

By November, Paxton was back in his office. The pain hadn’t gone away. He told her it was probably just the stress of the impending holiday season. It wasn’t implausible: “I was what you would consider a go-getter,” she tells me. “I have three boys. I was crazy about Christmas and the holidays. I volunteered for everything.” The doctor also reminded her that she’d had a clean mammogram of her dense breast tissue just seven months earlier.

“You again?” he asked when she returned to his office for the third time after the holidays. “If it would appease you, I’ll order an ultrasound,” he said. When she went in for the exam in January 2023, she could hear the doctors arguing outside her room. Then they told her they would perform a biopsy, too. The results began to come in the next day: The diagnosis was triple-negative, a difficult-to-treat form of cancer with a higher mortality rate. When Paxton finally met with an oncologist a week later, the doctor could feel the tumor immediately.

One reason doctors rarely order supplemental screens like MRIs is cost: MRIs are ten times more expensive than mammograms, and insurance companies almost never cover them. Under most plans, dense breasts alone do not qualify women for MRIs without being coupled with other risk factors such as family history and genetic markers. And if these supplemental screens aren’t covered, they can cost more than $1,000 out of pocket, which deters many women from getting them. MRI machines are also harder to find, especially in rural areas, and many health-care facilities and breast-screening centers don’t have them.

Meanwhile, mammograms remain such a staple requirement that I’ve encountered women who said that, even after their breast cancer was confirmed by a biopsy or an ultrasound, their insurance companies refused to pay for an MRI until they received a mammogram. Once, one of Kuhl’s patients had an MRI that detected breast cancer, but even with the positive result, her insurance denied coverage of the exam, demanding that she receive a mammogram. So Kuhl ordered one. It came back clean.

Even when doctors know that mammograms have missed breast cancer in a patient with dense breast tissue, they sometimes still rely on mammograms to screen for whether the cancer will return. Shamara Jackson Knowlton was in high school when her mother, Pamela, first felt a lump in her breast. Like many women, Pamela was always told she had dense breast tissue, but none of the doctors at her small-town clinic in Virginia had ever explained the significance of it. (Black women like Pamela are also more likely to have dense breast tissue.) After years of negative mammograms, Pamela was diagnosed with stage-three breast cancer in 2010 through her first MRI. She underwent chemo and radiation, and doctors continued to order mammograms to see whether the cancer had shrunk.

For years following Pamela’s treatments, Shamara believed her mother was doing well. They spoke daily on Shamara ’s drives to and from work, and her mother rarely mentioned cancer and seemed to be feeling better. In April 2012, Pamela received another mammogram and was told she had a clean bill of health, Shamara recalls. The doctors told her she was in remission.

Two months later, Pamela’s health began to deteriorate. It started with nasal congestion, which she believed was a sinus infection. Then in July, she passed out at work, and a CT scan and MRI of her brain didn’t yield clues why. By the end of the month, a golf-ball-size lump had appeared on the back of her neck, and she began to experience blurred vision.

Shamara had graduated college, and she began to accompany her mother to all of her appointments. She remembers how hard she had to push to get doctors to take her mother’s concerns seriously. “I think the biggest thing with my mom and so many women is not being an advocate because they don’t know what questions to ask,” Shamara tells me. “I’d say, ‘My mom has very dense breasts. Instead of just doing a mammogram, why aren’t we doing an MRI? Are we going to do an ultrasound as well?’ ” After parsing medical studies online, Shamara started to worry the lump on her mother’s neck could signal the return of cancer, but doctors ruled out the possibility when a spinal tap did not detect cancer cells in her spinal fluid.

By mid-August, Pamela had gone blind. One afternoon in September, Shamara was at the playground with her son when her phone rang. It was Pamela. She had just learned that the lump in her neck was, in fact, cancer, and that it had metastasized from her breast to the back of her neck and her brain. Pamela was told she had six to eight weeks to live.

For Shamara, the news made for the worst kind of vindication. “It was gut-wrenching,” she tells me. “I had been at that hospital for two or three weeks. I still remember the doctor sitting on the stool beside my mom’s bed, and my sister and I standing up, saying, ‘She has to have brain cancer.’” Shamara helped her mother get into a cancer-treatment center in Philadelphia, but by the following year, it was clear there were no further treatments that could help her. Pamela was placed on hospice until she died in May 2013.

Last year, bills to mandate insurance coverage of supplemental screens like MRIs for high-risk women were enacted in 11 states. In Pennsylvania, a law went into effect in 2022 that requires insurance companies to cover breast MRIs for high-risk women. As of early 2024, 20 states have passed legislation decreasing out-of-pocket costs for supplemental scans doctors deem medically necessary. Other bills are sitting before Congress, like the Access to Breast Cancer Diagnosis Act and the Find It Early Act, which both attempt to eliminate all out-of-pocket costs for screening, including MRIs.

Still, the health-care community is divided about the cost-effectiveness of providing MRIs for women with dense breasts. Port, for instance, pointed out that mammograms are the most cost-effective screening tool and that overall they save many lives. It’s not feasible, she believes, to offer an MRI to every woman with dense breasts. “Why don’t 20-year-olds get colonoscopies?” she asks. “Why don’t we do screening CT scans for lung cancer in every single person?” There are risks with every procedure, even those generally considered safe, and further testing could lead to more opportunity for harm: A false positive on an MRI scan could lead to an unneeded biopsy, for example. Port believes MRIs should be reserved for women with both dense breasts and some other form of increased risk, such as family history.

In one influential 2009 paper, researchers developed a predictive model that concluded that, while MRIs may be more sensitive than mammograms for high-risk women, the additional number of quality-adjusted years that routine breast MRIs could add to their lives was not much higher than the number added by routine mammograms. Meanwhile, the model found that MRIs would cost $18,200 over 25 years, while mammograms would cost only $4,800. (The study was partially funded by the PhRMA Foundation, a nonprofit that receives donations from pharmaceutical companies that make many of the world’s top-selling cancer drugs.)

In April 2024, a national panel of health experts at the United States Preventive Services Task Force issued its latest recommendations for breast-cancer screening. The task force is enormously influential, in large part dictating what most private and government-funded insurance companies will cover. This year, it concluded that, even for women with dense breasts, there wasn’t sufficient evidence to assess “the balance of benefits and harms of supplemental screening” like ultrasounds or MRIs. In its recommendations, the task force cited a number of studies. One of them, based on historical insurance claims, suggested that MRIs are more likely to lead to “cascade events” — visits to the doctor’s office, hospitalizations, and new diagnoses. Since the USPSTF’s list of recommended preventative services won’t include additional screening tools like MRIs based on breast density alone, insurance companies will not have to cover them.

Some advocates are suspicious of this line of logic about the cost of MRIs. “The way federal bills are scored, they don’t look at the future savings. We know that if you can get people into this imaging, you’re likely going to catch their disease earlier,” says Molly Guthrie, vice-president of policy and advocacy at Susan G. Komen. “It’s also going to be cheaper for the health-care system and for the insurers,” she continues, “because you’re going to be treating someone with early-stage breast cancer compared to stage four, when they’ll be in treatment for the rest of their life.”

Guthrie hopes it’s only a matter of time before insurance policies catch up with the current research. “It wasn’t that long ago that people had to pay out of pocket for their yearly mammograms,” she says. Insurance companies were only required to begin covering them after the Affordable Care Act included such preventative services through the USPSTF in 2010. Meanwhile, radiologists like Kuhl are optimistic about an alternate form of the test called abbreviated MRIs. They take place in the same machine, but the procedure is completed in under ten minutes at a fraction of the cost.

On the September day that Angie McCoy learned she had advanced breast cancer, she dialed her husband’s number and matter-of-factly reported what the doctor had told her. But when she called her best friend, her composure dissolved. It took saying the information aloud a second time for it to start sinking in. “I literally could not get the words out of my mouth,” she recalls. “I couldn’t feel my lungs. It’s like my body was convulsing in fear.” Stage-four breast cancer: “I’d done enough reading to know what that meant,” she says. “That meant that I would have a shortened lifespan and that I would be in treatment for the rest of my life.”

From October 2021 until February 2022, McCoy had six rounds of four-hour-long chemo infusions that brought near-constant bouts of nausea, diarrhea, and fatigue. Even when chemo and radiation help control it, a diagnosis of stage-four breast cancer can mean a lifetime of cancer therapies. Today, McCoy takes a handful of pills daily and gets regular infusions of Herceptin and Perjeta, two drugs that target her specific form of cancer, through a permanent chest port. The drugs cost thousands of dollars per dosage, though McCoy has good insurance that covers the medications after they hit the deductible. She sees an oncologist every other month and gets an echocardiogram every three months and a PET scan every six.

While she was undergoing chemo, her son Jacob was finishing his final semester at Oklahoma City University with a degree in music composition. His senior capstone project was an orchestral performance of his own original composition. McCoy’s immune system was battered from the treatments, and a COVID variant was surging, so her son’s professor arranged for her family to watch the performance from an observation room away from the rest of the audience.

Both Jacob and his elder brother are in their 20s; McCoy had them young enough that she had always assumed she would be there for the big moments in their lives: college graduations, marriages, grandchildren. Now, all of that felt uncertain. “You’re messing with people’s lives when you don’t go the extra yard and send us for a breast MRI,” McCoy says. “Women like me are paying for it in lost time. It’s a little black cloud over your head all the time: How many more years do I have?”