Fustanella

Fustanella (for spelling in various languages, see chart below) is a traditional pleated skirt-like garment that is also referred to as a kilt worn by men in the Balkans.

The Albanian and greek traditional costume with fustanella had identified the special troops that Albanians constituted within the Ottoman Empire, whose military prowess became renowned, especially in the era of the Ottoman Albanian pashas Ali of Yanina and Muhammad Ali of Egypt.[1] During the late 18th and early 19th centuries Albanian warriors wore it in the Kingdom of Naples and the Ionian Islands.[2] In the 1810s, the Albanian warrior dress was officially adopted by a British regiment in the Ionian Islands.[3] In the 1820s, it became a principal visual symbol of Philhellenism, and during the Greek War of Independence it was worn by the revolutionary fighters.[4] At that time its notoriety as a symbol of male bravery and heroism grew considerably across the Ottoman Empire and spread throughout Europe.[5] Following the Greek independence, fustanella and accompanying embroidered waistcoats and jackets were adopted by the nascent Greek army. In 1835, it was proclaimed the official court costume and eventually it became the Greek national dress.[6] The Albanian-Greek attire thereafter acquired popularity among peoples who wanted to dress in a courageous heroic manner.[5]

In modern times, the fustanella is part of Balkan folk dresses. In Greece, a short version of the fustanella is worn by ceremonial military units such as the Evzones since 1868. In Albania it was worn by the Royal Guard in the interbellum era. Both Greece and Albania claim the fustanella as a national costume.[7]

Origins

[edit]A terracotta figurine with a fustanella garment (i.e. a pleated skirt wore by a man) was found in Durrës, in present-day central Albania, dating back to the 4th century CE, clearly providing an early archaeological evidence of a fustanella.[8]

According to a hypothesis the fustanella was originally worn by the Illyrians.[9][8] It has been claimed that in the 13th century the fustanella was a common dress for Dalmatian men, regarded as one of the Illyrian ancestors of the Albanians.[9] Sir Arthur Evans said that the Albanian fustanella of the female peasants (worn over and above the Slavonic apron) living near the modern Bosnian-Montenegrin borders was a preserved Illyrian element among the local Slavic-speaking populations.[10]

Some scholars have hypothesised that the Albanian/Illyrian kilt became the original pattern of Roman military dress.[9] Baron Franz Nopcsa further theorized that the Celtic kilt emerged after the Albanian kilt was introduced to the Celts in Britain by the Roman legions.[9]

Some scholars have suggested a Roman origin, relating the fustanella to the statues of Roman emperors wearing knee-length pleated tunics.[11][12][13] According to a variant of this view, with the expansion of the Romans to colder climates in central and northwestern Europe, more folds would be added to provide greater warmth;[11][12] according to another variant of this view by folklorist Ioanna Papantoniou, the fustanella ultimately originated from the Celtic kilt, as viewed by the Roman legions, serving as the original prototype.[9]

Concerning the kilts, they are generally regarded as not being worn by Celtic warriors of Roman times and as being introduced in the Scottish Highlands c. 16th Century AD.[14][15]

Other scholars have hypothesised that the fustanella was derived from a series of ancient Greek garments such as the chiton (or tunic) and the chitonium (or short military tunic).[17][18] This hypothesis involves a link to an ancient statue (3rd century BC) located in the area around the Acropolis in Athens.[19][9] However, no ancient Greek clothing has survived to confirm that the origins of the fustanella are in the pleated garments or chitons worn by men in Classical Athens.[9]

In the Byzantine Empire, a pleated skirt known as the podea (Greek: ποδέα) was worn.[20][21] The wearer of the podea was either associated with a typical hero or an Akritic warrior and can be found in 12th-century finds attributed to Emperor Manuel I Komnenos (r. 1143–1180).[21]

Usage

[edit]Albania

[edit]In Albanian territories the fustanella was used centuries before Ottoman rule.[24] A fustanella is depicted on a 13th-century proto-maiolica pottery fragment from Durrës.[25] A 14th-century document (1335) listing a series of items including a fustanum (a cloth made of cotton), which were confiscated from a sailor at the port of the Drin River in the Skadar Lake region of Albania.[26] In the late Byzantine period and the early Ottoman period southern Albanians migrated in Greece and in southern Italy, bringing with them their own custom, language and clothing, which included the fustanella garment.[27][28][29][30][31] In the 19th century the usage of the fustanella stretched through all Albanian inhabited lands, and it had become the ethnic costume characteristic of the Albanian men.[32]

The Albanian traditional costume with fustanella had identified the special troops that Albanians constituted within the Ottoman Empire, whose military prowess became renowned, especially in the era of the Ottoman Albanian pashas Ali of Yanina and Muhammad Ali of Egypt.[1] In the Napoleonic era (1799–1815) the Albanian mercenary troops (Muslim Arnaut), whose traditional costume included the fustanella, were counted among the paid Turkish government troops, along with the Janissary troops. After the disbandment of Janissary corps in 1826, the Albanian troops were employed in various armies as frontier battalions when the new Mansure Army was established within the Ottoman army by Mahmud II. In the 1820s the authorities of the Ottoman Provincial Governments overall preferred Arnaut mercenary troops over any of the standing army troops.[33]

During the late 18th and early 19th centuries Albanian warriors wore their traditional costume with fustanella in the Kingdom of Naples and the Ionian Islands.[2] Between 1807 and 1814 it was worn by the men of the Albanian Regiment of the French army, which consisted mainly of Albanian warriors.[22] In the 1810s, the Albanian warrior dress was officially adopted as the standardised military uniform of the 1st Regiment Greek Light Infantry of the British army, which consisted mainly of Albanians and Greeks.[38]

The fustanella was regarded by foreign scholars and travellers as a typical Albanian costume, characterizing the Albanians from the standpoint of dress for many centuries, especially in the 18th and 19th centuries.[32] In 1805 William Martin Leake reported that it was worn by the men at arms of Albanian beys in the Morea, and that "The Albanian dress is daily becoming more customary, both in the Morea and in the rest of Greece".[39] In 1807 Leake reported that the officials of the Albanian ruler Ali Pasha of Yanina, including his sons, were dressed according to the Albanian tradition.[40] In 1809–1810, within the area of contemporary southern Albania and northwestern Greece, British traveller John Cam Hobhouse noticed that when traveling from the Greek-speaking area (region south of Delvinaki) into the Albanian-speaking area (to the direction of Gjirokastër and its surrounding environs), apart from different languages a change of clothing occurred.[41] Those Albanian speakers wore the Kamisa shirt and kilt, while Greek speakers wore woolen brogues.[41]

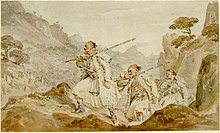

In the early 19th century, other British travellers within the region noticed the Albanian costume, in particular in 1809 Lord Byron celebrated and described it as "the most magnificent in the world, consisting of long, white kilt, gold-worked cloak, crimson velvet gold laced jacket and waist-coat, silver mounted pistols and daggers".[42] The renowned Albanian clothes were not official uniforms adorned with insignia, but traditional costumes with small differences depending on the regional location or personal preferences of the wearer.[43] After its celebration and description by Byron, who was the most influential Philhellene of the time,[43][44][31] the Albanian traditional warrior costume became a principal visual symbol of Philhellenism in the 1820s,[43][45][46][47][44] appearing in the widespread romantic iconography of klepht and armatole warriors of the Greek revolution.[43][44] The Albanian traditional costume with fustanella was greatly favoured among the Balkan peoples, and it was imitated by many other peoples. Its spread among other neighbouring peoples such as the Greeks, and even the Turks, is documented by the historians of the time.[48]

In 1848–1849, British painter Edward Lear traveling within the area of contemporary Albania observed that the fustanella was for Albanians a characteristic national costume.[50] Other artists visiting southern Albania in mid-19th century depicted landscapes with Albanians in traditional costume with fustanella, such as Henry Cook and George de la Poer Beresford.[51]

During the 19th century the use of the fustanella was worn over tight fitting tirq pants amongst male Albanian Ghegs by village groups of the Malësorë or highlanders of the Kelmend, Berisha, Shala and Hoti tribes.[52] They reserved use of the fustanella for elites during important and formal occasions such as dispute resolutions, election of local tribal representatives and allegiance declarations.[52] During the 1920s, the fustanella began to go out of fashion among Tosks being replaced with Western style clothing made by local tailors.[53]

The Albanian fustanella has around sixty pleats, or usually a moderate number.[55] It is made of heavy home-woven linen cloth.[55] Historically, the skirt was long enough to cover the whole thigh (knee included), leaving only the lower leg exposed.[55] It was usually worn by wealthy Albanians who would also expose an ornamented yataghan on the side and a pair of pistols with long-chiseled silver handles in the belt.[55] The general custom in Albania was to dip the white skirts in melted sheep-fat for the double purpose of making them waterproof and less visible at a distance.[56] Usually, this was done by the men-at-arms (called in Albanian trima).[56] After being removed from the cauldron, the skirts were hung up to dry and then pressed with cold irons so as to create the pleats.[56] They then had a dull gray appearance but were not dirty by any means.[56]

The jacket, worn with the fustanella in the Albanian costume, has a free armhole to allow for the passage of the arm, while the sleeves, attached only on the upper part of the shoulders, are thrown back.[55] The sleeves are not usually worn even though the wearer has the option of putting them on.[55] There are three types of footwear that complement the fustanella: 1) the kundra, which are black shoes with a metal buckle, 2) the sholla, which are sandals with leather thongs tied around a few inches above the ankle, 3) the opinga, which is a soft leather shoe, with turned-up points, which, when intended for children, are surmounted with a pompon of black or red wool.[55]

In 1914, the newly formed Greek armed forces of the Autonomous Republic of Northern Epirus (1913–1914) initially did not have their own military uniforms, but later the enlisted men adopted Evzone uniforms.[58] Nowadays among the Greek population in southern Albania, a sigouni, a sleeveless coat made of thick white wool, is worn over the fustanella in the regions of Dropull and Tepelenë.[59]

Bulgaria

[edit]The Albanian traditional warrior costume with fustanella spread among Bulgarians, about two decades after it was dressed by the revolutionaries of the Greek War of Independence in the 1820s, when its notoriety as a symbol of male courage and heroism expanded across the region. The Albanian-Greek attire became popular particularly among young men who wanted to take a picture in a heroic pose, although not being themselves involved in fights for independence.[47]

Egypt

[edit]

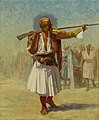

The sizeable Albanian guards and janissary troops who settled on the banks of the Nile during the early rule of Mehmed Ali' dynasty were noted for their swagger, their weapons and their costumes, particularly for the pleats of their typical white fustanellas. Those costumes played a major role in Jean-Léon Gérôme's paintings.[60]

Albanian volunteers and mounted infantry were called Arnauts in Egypt, and they were greatly valued in the Egyptian Army, especially for their traditional role as skirmishers, experts of mountain fighting, patrolling and bodyguard units. Contemporary commentators about their dress described their fustanella as "a white many folded" and "a white linen petticoat of enormous size, hanging in numberless plaits from the waist to the knee".[61]

In the 1930s the fustanella continued to characterise Albanian guards in Egypt, as witnessed by Egyptian scholar Magdi Wahba around the department stores in Cairo.[62]

Greece

[edit]

It has been suggested that the fustanella was already in common use in Greek lands as early as the 12th century.[64][63] Byzantine warriors, in particular the Akritai, wearing fustanella, are depicted in contemporary Byzantine art.[64][65] On Byzantine pottery sherds from Greece, Cyprus,[64] and Chersonesus,[66] warriors are shown bearing weapons and wearing the heavy pleated fustanella.[67] This is also confirmed by the Medieval Greek acritic songs of the 12th century;[68] it has been suggested that 11th-century illuminated manuscripts of the songs served as prototypes for later depictions.[64] The garment is also depicted on early 14th-century frescoes in the church of Saint Nicholas Orphanos in Thessaloniki, and the church of Holy Cross of Agiasmati in Cyprus.[64] The full-pleated fustanella was worn by the Byzantine Akritic warriors originally as a military outfit, and seems to have been reserved for people of importance.[63][69] It was frequently worn in conjunction with bows, swords, or battle-axes and frequently shown covered with a jointed corselet, or with a vest of chain mail.[63] Being a suitable garment for guerrilla mountain units, it might have been worn by the klephts of the Greek Revolution of 1821–1830 for the same reason it would have been worn by the akritai warriors of the Byzantine era earlier.[70]

Southern Albanians introduced their traditional costume with fustanella when they migrated in territories of present-day Greece,[73][28][74][75][76][31] subsequently becoming part of the national dress of Greece as a consequence of their settlement in the region.[77][78][79][31] The Albanian warrior dress with fustanella spread among armed irregulars – klephts and armatoles[45][46][47][44] – in the pre-revolutionary period,[80] and was worn by revolutionary fighters during the Greek War of Independence.[45][46][47][44][81][82][31] In the early 19th century, the costume's popularity rose among the Greek population.[83][84] During the era of post-independence Greece, parts of Greek society such as townspeople shed their Turkish-style clothing and adopted the fustanella which symbolised solidarity with new Greek democracy.[85] Philhellene enthusiasm for the fustanella survived knowledge of its Albanian origins.[76] It became difficult thereafter to distinguish the fustanella as clothing worn by male Arvanites from clothing worn by wider parts of Greek society.[85] Its popularity in the Morea (Peloponnese) was attributed to the influence of the Arvanite community of Hydra and other Albanian-speaking settlements in the area.[83] The Hydriotes however could not have played a significant role in its development since they did not wear the fustanella, but similar costumes to the other Greek islanders.[83] In other regions of Greece the popularity of the fustanella was attributed to the elevation of Albanians as an Ottoman ruling class such as Ali Pasha, the semi-independent ruler of the Pashalik of Yanina.[83] In those areas, its lightweight design and manageability in comparison to the clothing of the Greek upper classes of the era also made it fashionable amongst them in adopting the fustanella.[83]

The Albanian-style costume with fustanella was used in the Ionian Islands by the Albanian warriors, initially within an Albanian militia that was raised by the Russians in 1799, and which was transferred to the French in 1807, after the recovering of the Ionian Islands. On 12 October 1807 Napoleon also approved the recruitment of roughly 3,000 Albanians who had moved to the Ionian Islands, for the most part refugees fleeing the Albanian coast because of the harsh authority of the Ottoman Albanian ruler Ali Pasha of Janina.[22] On 12 December 1807 they were organized as the Albanian Regiment. Local Greeks, Italians and Dalmatians were additionally recruited, however the regiment never achieved its official establishment of 3,254.[90]

The first time the fustanella was worn as part of a standardised military uniform in territories of present-day Greece was in 1810 in the British regiment of Zakynthos, which consisted mainly of Albanians and Greeks.[38] The men of the regiment were reported as wearing "Albanian dress"; their orders stated "clothing and accoutrements were to be made in the Albanian fashion". Enlisted men wore red jackets with yellow cuffs, facings, and trim; for the officers, these were gold and white, over a white shirt, foustanella, breeches and stockings.[38]

In the Peloponnese, the Greeks of Mani did not traditionally wear the fustanella, they used to dress voluminous trousers. Written evidence that some version of the Albanian costume were in use in the Pelopponese was provided by William Martin Leake in March 1805, when he met a local Albanian Bey accompanied by Albanian soldiers. Leake also wrote about the Albanian costume during a visit to Hassan Bey, governor of Monemvasia, reporting that "The Albanian dress is daily becoming more customary, both in the Morea and in the rest of Greece; in the latter from the great increase of the Albanian power; in the Morea, probably in consequence of the prosperity of Ydhra, which is an Albanian colony, and of the settlements of Albanian peasantry that have been made in some parts of the Morea, particularly Argolis, as well as in the neighbouring provinces of Attica and Boeotia."[39]

Following the Greek independence, fustanella and associated embroidered waistcoats and jackets that were worn by the revolutionary fighters were adopted by the nascent Greek army. In 1835, it was proclaimed the official court costume by King Otto of Greece and eventually it became the Greek national dress.[6]

During the reign of King Otto (1832–1862), the fustanella was worn by the king, the royal court and the military, while it became a service uniform imposed on government officials to wear even when abroad.[91][92] In that period the dress system in Greece evolved, and most of the Greeks were increasingly wearing European garments, while traditional clothing was still preserved in villages. The uniform with the typical fustanella was mainly used in the army as well as on ceremonial events and feasts.[93]

In the Crimean War (1853–1856), fustanella was worn by volunteers serving in the Greek Volunteer Legion.[94] In 1855, it was insisted that the Greek volunteers should abandon the fustanella and adopt uniforms that were similar to the Russian ones; arguing that the costume of the Greeks was not suitable for military conditions. Aristidis Chrisovergis, one of the commanders, strongly opposed this and refused to take off the fustanella.[95]

Greek villagers of Albanian origin continued to wear the fustanella or the poukamiso (an elongated shirt) on a daily basis until the 20th century.[81] Of the Roumeliotes, the nomadic Greek-speaking Sarakatsani pastoralists wore either trousers or the fustanella, depending on the local tradition.[96] The Aromanians, a Latin-speaking people who lived within Greece also wore the fustanella or trousers depending on the region.[96]

In terms of geographical spread, the fustanella never became part of the clothing worn in the Aegean islands, whereas in Crete it was associated with the heroes of the Greek War of Independence (1821) in local theatrical productions and seldom as a government uniform.[97] The men of the Greek presidential guard, founded in 1868, wear the fustanella as part of their official dress.[98] By the late 19th century, the popularity of the fustanella in Greece began to fade when Western-style clothing was introduced.[92][97]

The fustanella film (or fustanella drama) was a popular genre in the Greek cinema from 1930s to 1960s.[99] This genre emphasized on depictions of rural Greece and was focused on the differences between rural and urban Greece. In general it offered an idealized depiction of the Greek village, where the fustanella was a typical image.[100] In Greece today, the garment is seen a relic of a past era with which most members of the younger generations do not identify.[101]

The Greek fustanella differs from the Albanian fustanella in that the former garment has a higher number of pleats. For example, the "Bridegroom's coat", worn throughout the districts of Attica and Boeotia, was a type of Greek fustanella unique for its 200 pleats; a bride would purchase it as a wedding gift for her groom (if she could afford the garment).[102] A fustanella is worn with a yileki (bolero), a mendani (waistcoat) and a fermeli (sleeveless coat). The selachi (leather belt) with gold or silver embroidery, is worn around the waist over the fustanella, in which the armatoloi and the klephts placed their arms.[103]

During the 18th and early 19th centuries, the skirts hung below the knees and the hem of the garment was gathered together with garters while tucked into the boots to create a "bloused" effect. Later, during the Bavarian regency, the skirts were shortened to create a sort of billowy pantaloon that stopped above the knee; this garment was worn with hose, and either buskins or decorative clogs. This is the costume worn by the Evzones, light mountain troops of the Hellenic Army. Today it is still worn by the ceremonial Presidential Guard.[98]

Italy

[edit]

The fustanella has been in usage among the Arbëreshë people since their arrival in Italy.[104]

In the late 18th century the Albanian traditional warrior costume with fustanella was worn by the Albanian troops in the Kingdom of Naples.[105] The Albanian Regiments were disbanded in 1789, however they were restored in 1798 constituting the "Albanian Volunteer Hunters Battalion" (Italian: "Battaglione Cacciatori Volontari Albanesi"). In 1800 they merged into the Royal Macedonian Regiment (It. "Real Macedonia"), where soldiers were recruited from their homeland until 1812, when the Regiment was disbanded. In 1813 the 526 veterans were sent to their homeland. In 1815, King Ferdinand of Naples commissioned the British General Richard Church to reorganize the Royal Macedonian Regiment called "Macedonian Hunters" (It. "Cacciatori Macedoni") or "Royal Albanian" (It. "Real Albanese") or "Royal Hunters" (It. "Reali Cacciatori").[105] In 1818 the unit was incorporated into the "Foreign Regiment" (It. "Reggimento Esteri"), constituting in 1820 its 3rd Battalion that was called "Foreign Hunters" (It. "Cacciatori Estero"). It was disbanded on 6 July 1820 after the assassination attempt on King Ferdinand by the Arbëresh Agesilao Milani. Thereafter the exonerated soldiers were sent to their homeland.[106]

The fustanella has been a symbol of economic wealth among Arbëreshë people.[107] It is worn by Arbëreshë men during festivals.[107]

North Macedonia

[edit]In Macedonia, the fustanella was worn in the regions of Azot, Babuna, Gevgelija, the southern area of the South Morava, Ovče Pole, Lake Prespa, Skopska Blatija, and Tikveš. In that area, it is known as fustan, ajta, or toska. The use of the term toska could be attributed to the hypothesis that the costume was introduced to certain regions within Macedonia as a cultural borrowing from the Albanians of Toskëria (subregion of southern Albania).[108]

Moldova and Wallachia

[edit]

In the 18th and 19th centuries many foreign travellers recorded that the bodyguards of the princely courts of Moldova and Wallachia were dressed with the Albanian fustanella.[48]

Turkey

[edit]In the Napoleonic era (1799–1815) the Albanian mercenary troops (Muslim Arnaut), whose traditional costume included the fustanella, were counted among the paid Turkish Government Troops, along with the Janissary troops.[33]

In 1808 Albanian Troops of Bayraktar Mustafa Pasha marched beside the new Sultan Mahmud II along Divan Yolu, the Imperial Road that led to the Imperial Council from Constantinople, following the Sultan's Sword Girding.[33]

In the 1820s the authorities of the Ottoman Provincial Governments overall preferred Arnaut mercenary troops over any of the standing army troops. After 1826 these Albanian troops were employed in various armies as frontier battalions when the new Mansure Army was established within the Ottoman army by Mahmud II.[33]

In the 19th century Albanian warriors found immediate employment remarkably in Istanbul, hired as guards of foreign embassies and the homes of the wealthy. They wore their traditional dress with fustanella, which evolved from an untidy costume into a formal uniform that exhibited the status of their employers.[109]

In the Baklahorani annual carnival of the Greek community in Istanbul the traditional fustanella was among the popular costumes worn by the Greek youth.[110]

United States

[edit]In the United States, the fustanella is identified with Albanian and Greek populations. It can be frequently seen in Albanian and Greek folk festivals and parades across the country.[111]

Name

[edit]The word fustanella derives from Italian fustagno 'fustian' and -ella (diminutive), the fabric from which the earliest fustanella were made. This in turn derives from Medieval Latin fūstāneum, perhaps a diminutive form of fustis, "wooden baton". Other authors consider this a calque of Greek xylino (ξύλινο), literally "wooden" i.e. "cotton";[112] others speculate that it is derived from Fostat, a suburb of Cairo where cloth was manufactured.[113]

The garment is also known by other names; including tsamika/çamika, associated with the ethnonym of the Albanian sub-group Chams,[114] and kleftiki, associated with brigands known as klephts.[115]

Name in various languages

[edit]Words for "skirt" and "dress" included for comparison.

| Language | Short skirt | Skirt | Dress |

|---|---|---|---|

| Albanian | fustanellë/fustanella | fund | fustan |

| Aromanian | fustanelã | fustã | fustanã |

| Bulgarian | фустанела (fustanela) |

фуста (fusta) |

фустан (fustan) |

| Greek | φουστανέλλα (foustanélla) |

φούστα (foústa) |

φουστάνι (foustáni) |

| Italian | fustanella | gonna | |

| Macedonian | фустан (fustan) |

фустан (fustan) |

фустан (fustan) |

| Megleno-Romanian | fustan | fustan | |

| Romanian | fustanelă | fustă | |

| Serbo-Croatian | фустанела fustanela |

фистан fistan |

фистан fistan |

| Turkish | fistan |

Gallery

[edit]-

Ioryi Mucitano, the first leader of the first Aromanian band in the IMRO.

-

A Greek and an Albanian wearing the Fustanella costume, Russia, 1862.

-

Macedonian costumes at the Museum of North Macedonia in Skopje.

-

Greek General of the Royal Phalanx in full dress uniform, 1835.

-

Spiridon Louis, Olympic marathon champion (1896).

-

At the carnival in Venice, painting by Mikhail Scotti.

-

Greek Presidential Guard officer, Athens.

-

Albanian in Cairo, by Jean-Léon Gérôme, c. 1880

-

Albanian leader Hamza Kazazi, photographed c. 1858

-

Black fustanella, worn by Greek Macedonian.

-

Royal Guard of Albania in 1921.

-

Ilyo Voyvoda was a Bulgarian Macedonian revolutionary (1867).

-

Souliote Warrior by Louis Dupré, 1820.

-

Guard of honour at the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier, Syntagma Square, Athens, 2006.

-

Changing of the guards at the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier, 2005.

-

Sarakatsani in Thrace, 1938.

-

Albanian Officer by Jean-Léon Gérôme, 1894.

-

A Greek in Crimea, 19th century

See also

[edit]References

[edit]Citations

[edit]- ^ a b Volait 2021, p. 202; Flaherty 2023, pp. 38–39; Scarce 2017, pp. 159–164, 170–172.

- ^ a b Romagnoli 2010, p. 68; Brnardic 2004, pp. 37–38

- ^ Chartrand & Courcelle 2000, p. 20.

- ^ Volait 2021, p. 202; Baleva 2021, pp. 77–85; Baleva 2017, pp. 241–243; Scarce 2017, pp. 170–172.

- ^ a b Baleva 2021, pp. 77–85; Baleva 2017, pp. 241–243.

- ^ a b Volait 2021, p. 202; Scarce 2017, pp. 158, 170–172.

- ^ Koço 2004, p. 161

- ^ a b Andromaqi Gjergji (2004). Albanian Costumes Through the Centuries: Origin, Types, Evolution. Academy of Sciences of Albania, Inst. of Folc Culture. p. 209. ISBN 978-99943-614-4-1.

- ^ a b c d e f g Skafidas 2009, p. 148.

- ^ Evans 2006, p. 126: "The peasant women, whose attire through this and the adjoining Serbian provinces is as exclusively Slavonic as their language, have here preserved a distinctively Illyrian element in their dress. They wear, in fact, over and above the Slavonic apron, an Albanian fustanella;".

- ^ a b Keramopoulos, Antonios (1953). "Η φουστανέλλα". Λαογραφία (in Greek). Vol. 15. Ελληνική Λαογραφική Εταιρεία. pp. 239–240, 243.

- ^ a b Notopoulos 1964, p. 114

- ^ Papantoniou, Ioanna (2000). Greek Dress: From Ancient Times to the Early 20th Century. Εμπορική Τράπεζα. p. 208. ISBN 978-960-7059-11-6.

Keramopoullos's theory that the fustanella was descended from the Roman military uniform seems to me more likely.

- ^ "Brief History of the Kilt - the Scottish Tartans Museum and Heritage Center, Inc".

- ^ "The History of Irish Kilts". 17 October 2019.

- ^ Kyrou, Adonis K. (2020). "The Cave of Nympholeptos: From the dances of the Nymphs to neoplatonic contemplation". KYDALIMOS: Studies in Honor of Prof. Georgios St. Korres, Vol. 3 (in Greek). National and Kapodistrian University of Athens. p. 157. ISBN 978-960-466-231-9.

Πρόκειται για τη, λίγο μεγαλύτερη του φυσικού, ανάγλυφη απεικόνιση του Αρχεδήμου, λαξευμένη από τον ίδιο επάνω στην επιφάνεια του ενδιάμεσου βραχώδους σχηματισμού, που όπως είδαμε χωρίζει το σπήλαιο σε δύο μεγάλους θαλάμους. Φορώντας βραχύ χιτώνα, δεμένο σε πτυχές στη μέση σαν φουστανέλα (εύζωνος, από το επίρρημα ευ και το ρήμα ζώνυμι), όπως συνήθιζαν οι αρχαίοι σε ώρες γεωργικής ή άλλης χειρωνακτικής απασχολήσεως, ...

- ^ Smithsonian Institution & Mouseio Benakē 1959, p. 8: "From the ancient chiton and the common chitonium (short military tunic), fastened by a belt round the waist and falling into narrow regular folds, is derived the fustanella which by extension gives its name to the whole of the costume."

- ^ Fox 1977, p. 56: "The young shepherd wears a fustanella, descendant of the military tunic of ancient Greece, now rarely worn except by certain regiments."

- ^ Lynch, Strauss, 2014, p. 126

- ^ Notopoulos 1964, pp. 110, 122.

- ^ a b Kazhdan 1991, "Akritic Imagery", p. 47: "While 35 plates have the warrior wearing the podea or pleated skirt (sometimes called a fustanella) attributed to Manuel I, the "new Akrites," in a Ptochoprodromic poem, and 26 have him slaying a dragon, neither iconographic element is sufficient to identify the hero specifically as Digenes because both the skirt and the deed characterize other akritai named in the Akritic Songs."

- ^ a b c Brnardic 2004, pp. 37–38.

- ^ Mesi 2019, p. 54.

- ^ Mesi 2019, p. 46: "The most common element in men's clothing is the white, long and multi-pleated fustanella, widely known as the garment, used centuries before the Ottoman occupation, by a large population living in the Albanian territories lying in the Balkans."

- ^ Hoti 1989, p. 224.

- ^ Gjergji 2004, p. 16: "Among the most important documents is one of the year 1335, which relates how at the port of Drin, near Shkodra, a sailor was robbed of the following items: (ei guarnacionem, tunicam, mantellum, maçam, de ferro, fustanum, camisiam abstulerunt). This is the earliest known evidence in which the "fustan" (kilt) is mentioned as an item of clothing along with the shirt."

- ^ Skafidas 2009, pp. 146–147.

- ^ a b Welters 1995, p. 59.

- ^ Verinis 2005, pp. 139–175.

- ^ Nasse 1964, p. 38: "The Albanian soldier who arrived in southern Italy during the days of Scanderbeg wore a distinctive costume; if he was a "Gheg" (northern Albanian), he wore rather tight breeches and a waistcoat; if he was a "Tosk" (southern Albanian), he wore a "fustanella" (a white pleated skirt) and a waistcoat."

- ^ a b c d e Langkjær 2012, p. 114.

- ^ a b Gjergji 2004, p. 115.

- ^ a b c d Flaherty 2023, pp. 38–39.

- ^ Beresford, G. de la Poer. "Janina, Albania (subsequently Greece): the audience chamber of Ali Pasha. Colour lithograph after G.D. Beresford, 1855". Artstor.

- ^ de la Poer Beresford, George (1855). Twelve Sketches in Double-tinted Lithography of Scenes in Southern Albania. London: Day and Son.

- ^ Hernandez, David R. (2019). "The Abandonment of Butrint: From Venetian Enclave to Ottoman Backwater". Hesperia. 88 (2): 365–419. doi:10.2972/hesperia.88.2.0365. S2CID 197957591. p. 408: "George de la Poer Beresford published 12 double-tinted lithographs of scenes from southern Albania in 1855.214"

- ^ Prokopiu, Geōrgios A. (2019). Archontika tēs Kozanēs: architektonikē kai Xyloglypta (PDF). Athens: Benaki Museum. p. 13. ISBN 978-960-476-261-3.

Εικ. 11. Η αίθουσα των ακροάσεων του Αλή-Πασά στα Γιάννενα (περί το 1800).

- ^ a b c d Chartrand & Courcelle 2000, p. 20: "The orders stipulated that 'clothing and accoutrements were to be made in the Albanian fashion'."

- ^ a b Scarce 2017, pp. 170–171.

- ^ Meço 2011, p. 405.

- ^ a b De Rapper 2005, pp. 182–183: "By the beginning of the nineteenth century and later on, the British, French and Austrian travellers who visited Lunxhëri, most of them arriving from Ioannina, described the Lunxhots as Albanian-speaking Orthodox Christians, and had the feeling that, starting north of Delvinaki, they were entering another country, although the political border did not exist at the time. Greek was not spoken as it was further south, there was a change in the way of life and manners of the peasants. As one traveller reported Hobhouse 1813: Every appearance announced to us that we were now in a more populous country. (...) the plain was every where cultivated, and not only on the side of Argyro-castro [Gjirokastër]... but also on the hills which we were traversing, many villages were to be seen. The dress of the peasants was now changed from the loose woollen brogues of the Greeks, to the cotton kamisa, or kilt of the Albanian, and in saluting Vasilly they no longer spoke Greek."

- ^ Athanassoglou-Kallmyer 1983, pp. 487–488: "Delacroix's fascination with the near east in the 1820s, in part as a result of his interest in the Greek War of Independence, accounts for a number of studies of oriental costumes, among which the best known are perhaps his oil sketches representing dancing Suliots (Fig. 38). A water-colour of Two Albanians, in a private collection in Athens, can now be related to this group of works (Fig. 34). Two chieftains are shown within a landscape that recedes towards a low, distant horizon. The man on the left poses in rather stiff contrapposto. His companion sits cross-legged, Oriental style. The standing man wears the white kilt, and embroidered vest and sash typical of Albanian dress...As opposed to the rather general handling of the setting, the figures are depicted with great specificity. Delacroix must have intended the latter to serve as mementoes, as records of ethnic types and dress, part of the process of collecting Orientalist visual imagery in which he was engaged in the 1820s. His enthusiasm at the lush beauty of the Albanian costume must have matched that of his favourite poet at the time, Byron. In a letter to his mother from Epirus dated 12 November 1809, Byron had marvelled at 'the Albanians, in their dresses, (the most magnificent in the world, consisting of long, white kilt, gold-worked cloak, crimson velvet gold laced jacket and waist-coat, silver mounted pistols and daggers)...he admitted to having succumbed to the temptation and acquired some of these 'magnificent Albanian dresses...They cost fifty guineas each, and have so much gold, they would cost in England two hundred'."

- ^ a b c d Suparaku 2013, p. 170.

- ^ a b c d e Scarce 2017, pp. 170–172.

- ^ a b c Volait 2021, p. 202.

- ^ a b c Baleva 2021, pp. 77–85.

- ^ a b c d Baleva 2017, p. 241–243.

- ^ a b Mesi 2019, p. 47.

- ^ Elsie, Robert (ed.). "Albania in the Painting of Edward Lear (1848)". albanianart.net.

- ^ Koço 2015, p. 17: "The closely observing eye of the painter Edward Lear, in his travels around Albania in 1848 and 1849, depicted the fustanella as a typical national costume of the Albanians."

- ^ Hernandez 2019, pp. 408–409.

- ^ a b Blumi 2004, p. 167: "While quite popular among those who depicted Malesorë life in paintings, the use of the foustanella among Ghegs was basically reserved for formal occasions; it was worn by groups in the Kelmendi, Hoti, Shala and Berisha village groups. On such important occasions such as declarations of allegiance, the settlement of disputes and the election of paramount representatives, elite males would adopt these long white garments and wear their tirq underneath. The foustanella became famous once King Otto of Greece declared it the national dress of independent Greece, probably due to the fact his largely Albanian speaking army wore it."

- ^ Tomes 2011, p. 44.

- ^ Elsie, Robert. "Ottoman Costumes 1873". albanianphotography.net.

- ^ a b c d e f g Konitza 1957, pp. 85–86.

- ^ a b c d Konitza 1957, p. 67.

- ^ Mehmed, Fenerci (1986). "86 – İşkodrali". In Ilhami Turan (ed.). Osmanlı Kıyafetleri [Ottoman Costume Book] (in English and Turkish). Istanbul: Vehbi Koc Vakfi.

- ^ Kaphetzopoulos, Ioannis; Flokas, Charalambos; Dima-Dimitriou, Angeliki (2000). The struggle for Northern Epirus. Hellenic Army General Staff, Army History Directorate, Hellenic Army General Staff. ISBN 9789607897404.

Initially, as there were no military uniforms, the enlisted men were distinguished by wearing a uniform head covering, made of a khaki material, with the sign of a cross, for enlisted men, and the double-headed eagle for officers, as well as a blue arm-band, and the initials of the Delvino Regiment (Sigma Delta). Later on, the situation improved, and all enlisted men wore Evzone uniforms.

- ^ Lada-Minōtou, Maria (1993). Greek Costumes: Collection of the National Historical Museum. Historical and Ethnological Society of Greece. p. xxvii.

There are, however, examples where the sigouni is worn over a pleated skirt of the foustanela type, as at Dropoli and Tepeleni in Northern Epirus

- ^ Elsie, Robert. "Jean-Léon Gérôme (1824-1904)". albanianart.net.

- ^ Flaherty, Chris (2021). "Arnaout: Albanian (mounted infantry) regiment". Turkish army Crimean war uniforms – Volume 2. Soldiers & Weapons. Vol. 41. Soldiershop Publishing. p. 23. ISBN 9788893277846.

- ^ Wahba 1990, pp. 103–104.

- ^ a b c d Morgan 1942, pp. 132–133: "Most of these men are warriors with long curling locks falling down their backs, clad in pleated tunics or chain mail with short pointed caps on their heads. They wield swords, and protect themselves with shields, either round or shaped like a pointed oval...The mace-bearer of No. 1275 is clad in chain mail with a heavy pleated fustanella worn about his hips. The importance of this latter piece is very considerable, for the details of the costume, often shown on Incised-Sgraffito figures, are very clear, and make it certain that the fustanella exists as an independent garment and is not an elaboration of the lower part of a tunic. It is consequently demonstrable that this characteristic garment of latter-day Greece was in common use as early as the twelfth century in Greek lands."

- ^ a b c d e Vroom 2014, pp. 170–171

- ^ Notopoulos 1964, p. 110: "These lines are triply valuable for they tell us (1) the early popularity of Akritas; (2) the existence of the source of the Grottaferrata by the twelfth century; (3) that Digenes wears kilts which appear in the Byzantine plates as the fustanella, the key for the identification of the warriors in the plates."

- ^ Doğer 2004, p. 89

- ^ Morgan 1942, pp. 133, 317–318, 333.

- ^ Notopoulos 1964, p. 113: "We can dispose of any lingering doubts as to the identification of the hero with Akritas rather than St. George or Alexander by considering one important piece of evidence that has not been exploited before, namely, the fustanella, the pleated kilt worn by the dragon slayers and by many other figures in the Byzantine plates. We have already seen that the twelfth century poet Prodromos describes Digenes as wearing kilts, a detail which is also mentioned in the Grottaferrata version. The Byzantine plates corroborate this key detail in the identification. Thirty-five plates show such warriors wearing the fustanella. Of these at least eight plates, on which the identification with Digenes rests, show a warrior slaying a dragon."

- ^ Notopoulos 1964, pp. 114: "They are not clad in armor, nor in helmets. They wear a cap, a cloth doublet, and their pleated kilt is unmistakably different from that of the other class of warriors. Their kilt resembles the klepht fustanella; it is longer, more flared, fluid, and ornamented with decorative stripes, horizontal or vertical. It is this difference in kilts that distinguishes the warriors in the Byzantine plates from the imperial forces depicted in other manifestations of Byzantine art. The kilts in our plates belong to the akrites, whose garb is required by their way of life and the guerrilla type of warfare described in the Byzantine military treatise."

- ^ Notopoulos 1964, pp. 113–115: "A comparison of the fustanella warriors on the Byzantine plates with the klephts of the Greek Revolution of 1821–30, shown in the primitive paintings of Makriyiannes, shows that we are dealing in both instances with a garment which is peculiarly suited to a fast, mobile guerrilla mountain type of warrior...This kind of warfare, also described in the Akritan ballads, called for a fast mobile guerrilla type of soldier. What kind of dress is suitable for this kind of warfare? Nothing better than the fustanella worn by the Akritan warriors in the Byzantine plates."

- ^ "Ιματιογραφία Γ΄ Ελλάς εν γένει". The American School of Classical Studies - Digital Collection.

Title: Albanais au service d' Ali Pacha. (ο τίτλος είναι γραμμένος με μολύβι εκτός πλαισίου εικόνας). Publication/Bibliography: Voyage a Athènes et a Constantinople ou collection de portraits, de vues et de costumes Grecs et Ottomans. Peints sur les lieux, d' aprés nature, lithographieés et coloriés par L. Dupré, éléve de David; Accompagné d' un texte orné de vignettes. Paris, Imprimarie de Dondey-Dupré, rue Saint-Louis, No 46, au Marais. M DCCC XXV.

- ^ Original quote: "Le 27 mars, avant de partir, je fis le croquis d’une mosquée et le portrait d’un jeune seigneur albanais (PI. X), qui, par forme de remercîment, tua et écorcha un mouton en notre présence. Je fus moins touché que surpris de sa politesse; mais je ne laissai pas de le regarder avec un intérêt qu’il attribuait sans doute à sa dextérité, et qui avait une tout autre cause. Son action venait de me rappeler les héros d’Homère, et de me transporter, sans qu’il s’en doutât, dans le camp d’Achille. Les traits et la tournure de cet Albanais prêtaient assez à l’illusion; il avait le front noble et le regard fier; il était couvert de dorures; ses armes étaient aussi éclatantes que celles qui furent forgées par Vulcain." (Tzortzakakis 2023, pp. 119–121)

- ^ Skafidas 2009, pp. 146–147.

- ^ Verinis 2005, pp. 139–175: "Thought originally to have been a southern Albanian outfit worn by men of the Tosk ethnicity and introduced into more Greek territories during the Ottoman occupation of previous centuries, the "clean petticoat" of the foustanéla ensemble was a term of reproach used by brigands well before laografia (laographía, folklore) and disuse made it the national costume of Greece and consequently made light of variations based on region, time period, class or ethnicity."

- ^ Tzanelli, Rodanthi (2008). Nation-Building and Identity in Europe: The Dialogics of Reciprocity. Palgrave Macmillan. pp. 78–80. ISBN 978-0-230-55199-2.

- ^ a b Maxwell 2014, pp. 170–171: "The foustanela, like the Scottish kilt or Lady Llanover's Cambrian Costumes, provides ample material for authenticity—fabrication debates, not least because its origins apparently lie in Albania. During the Greek independence war, however, its Greek connotations became so powerful that foreign Philhellenes adopted it to show their sympathy for the Greek cause. Henry Bradfield, a surgeon who served in Greece, observed one English gentleman who tried to make a foustanela from a sheet. Philhellene enthusiasm for the foustanela survived knowledge of its Albanian origins, Philhellene William Whitcombe described the foustanela as a light Albanian kilt" in his 1828 memoirs."

- ^ Bialor 2008, pp. 67–68 (Note #4): "Also, Albanians, Arvanito–Vlachs, and Vlachs, from the fourteenth until the nineteenth centuries, had settled major areas of Northwestern and Central Greece, the Peloponessos and some of the Saronic and Cycladic islands. Though usually remaining linguistically distinct, they participated "as Greeks" in the War of Independence and in the further development of the new nation. As a consequence of extensive Albanian settlement, the Greek national dress up until the twentieth century was the Albania foustanella (pleated skirt) with pom-pommed curved shoes called tsarouchia."

- ^ St. Clair 1972, p. 232: "Gradually, more and more Greeks found ways of getting themselves on the Government's pay roll. The money was never accounted for in detail. A captain would simply contract to provide a number of armed men and draw pay for that number. Again, the opportunities for embesslement were eagerly seized. Anyone who could muster any pretensions to a military status appeared in Nauplia demanding pay. It was probably at this time that the Albanian dress made its decisive step towards being regarded as the national dress of Greece. The Government party, being largely Albanians themselves, favoured the dress and a version of it was common among the Greek klephts and armatoli. Now it seemed that anyone who donned an Albanian dress could claim to be a soldier and share in the bonanza."

- ^ Skafidas 2009, p. 148: "The modern fustanella appears in Greece worn by Albanians, and especially the Arvanites, as Greeks of Albanian ancestry were called, most of whom fought alongside the Greeks against the Turks in the long war of independence."

- ^ Ethniko Historiko Mouseio 1993, p. xxx: "The foustanela was worn by the armatoli and klephts in the pre-revolutionary period and by the freedom-fighters in the War of Independence."

- ^ a b Speake, Graham (2021). Encyclopedia of Greece and the Hellenic Tradition. Taylor & Francis. p. 518.

- ^ Verinis 2005, pp. 139–175

- ^ a b c d e Angelomatis-Tsougarakis 1990, p. 106: "On the other hand, Albanian dress was daily becoming more fashionable among the other nationalities. The fashion in the Morea was attributed to the influence of Ydra, an old Albanian colony, and to the other Albanian settlements in the Peloponesse. Ydra, however, could not have played a significant part in the development since its inhabitants did not wear the Albanian kilt but the clothes common to other islanders. In the rest of Greece it was the steadily rising power of Ali Pasha that made the Albanians a kind of ruling class to be imitated by others. The fact that the Albanians dress was lighter and more manageable than the dress the Greek upper classes used to wear also helped in spreading the fashion. It was not unusual even for the Turks to have their children dressed in Albanian costume, although it would have been demeaning for them to do so themselves."

- ^ Gerolymatos 2003, p. 90: "Greek fashion in the nineteenth century saw men dressed in the Albanian kilt while women followed the Muslim tradition of covering themselves up, including the face and eyes."

- ^ a b Welters 1995, pp. 59: "According to old travel books, the nineteenth-century traveler could readily identify Greek-Albanian peasants by their dress. The people and their garb, labeled as "Albanian", were frequently described in contemporary written accounts or depicted in watercolours and engravings. The main components of dress associated with Greek-Albanian… men an outfit with a short full skirt known as the foustanella.", pp. 59–61. "Identifying the Greek-Albanian man by his clothing was more difficult after the Greek war of Independence, for the so-called "Albanian costume" became what has been identified as the "true" national dress on the mainland of Greece. In admiration for the heroic deeds of the Independence fighters, many of whom were Arvanites, a fancy version of the foustanella was adopted by diplomats and philihellenes for town wear.", pp. 75–76. "The townspeople who gave up their Turkish-style clothing after Greece attained its independence communicated solidarity with the new Greek democracy by wearing foustanella. This was clear example of national dress. At the same time, those who dwelled in villages and on mountainsides kept their traditional clothing forms, specifically the sigouni and the chemise."

- ^ Ελευθερία Νικολαΐδου (Eleutheria Nikolaidou) (1997). "Η Ήπειρος στον Αγώνα της Ανεξαρτησίας (Epirus in the Struggle for Independence)". In Μιχαήλ Σακελλαρίου (Michael Sakellariou) (ed.). Ηπειρος : 4000 χρόνια ελληνικής ιστορίας και πολιτισμού (Epirus: 4.000 years of Greek history and civilisation). Athens: Εκδοτική Αθηνών. p. 277.

Στήν εἰκόνα πολεμιστές Σουλιῶτες σέ χαλκογραφία τῶν μέσων τοῦ 19ου αἰ. (In the picture Souliote warriors from a 19th c. chalcography)

- ^ "drawing _ British Museum". Retrieved 3 November 2022.

Description: Albanian Palikars in pursuit of an enemy

- ^ "Σουλιώτες πολεμιστές καταδιώκουν τον εχθρό. - Hughes, Thomas Smart - Mε Tο Bλεμμα Των Περιγηηγητων - Τόποι - Μνημεία - Άνθρωποι - Νοτιοανατολική Ευρώπη - Ανατολική Μεσόγειος - Ελλάδα - Μικρά Ασία - Νότιος Ιταλία, 15ος - 20ός αιώνας". Retrieved 3 November 2022.

Πρωτότυπος τίτλος: View of Albanian palikars in pursuit of an enemy

- ^ Murawska-Muthesius, Katarzyna (2021). "Mountains and Palikars". Imaging and Mapping Eastern Europe: Sarmatia Europea to Post-Communist Bloc. Routledge. pp. 77–79. ISBN 9781351034401.

- ^ Brnardic 2004, p. 37.

- ^ Maxwell 2014, pp. 172: "Othon apparently arrived in Greece wearing a Bavarian military uniform, but soon adopted the foustanela (see Figure 8.1) not only for official portraits, but in daily life. Courtier Hermann Hettner wrote that the King habitually received guests in "the Greek national costume, resplendent in silver and gold." Othon dressed his court in foustanela as early as 1832, queen Amalia also dressed her ladies-in-waiting in analogous Greek costumes. The costume seems to have genuinely pleased Othon: after being forced from power in 1862, he continued to wear it in his German retirement. Othon also made the foustanela a service uniform by imposing it on government officials… Government officials also wore the foustanela abroad, which occasionally led to embarassment [sic] ... Othon showed less enthusiasm for the foustanela as a military uniform. He initially intended to use Bavarian-style uniforms in his army, but backed down when threatened with mass resignations and the resultant banditry."

- ^ a b Skafidas 2009, p. 150.

- ^ Scarce 2017, p. 172.

- ^ Todorova 1984, p. 544.

- ^ Todorova 1984, p. 559.

- ^ a b Welters 1995, p. 70: "The name Roumeliotes was applied to the Sarakatsani because centuries ago they returned to mainland Greece to pasture their sheep every summer (Koster and Koster 1976: 280)."; p. 63. "Sarakatsani men were not as uniform in their attire as Sarakatsani women. The men wore outfits made from handwoven wool with either trousers (panovraki) or foustanella skirts depending on the local tradition (Papantoniou 1981:11)."; p. 67. "Papantoniou associates two types of male garments with the Vlachs, the white trousers (of the type seen in Fig. 3.4) and the homemade foustanella (Papantoniou 1981: 11, 41). It should be remembered that both trousers and foustanella were also worn by Sarakatsani men."

- ^ a b Maxwell 2014, pp. 176: " By the end of the nineteenth century, the foustanela was no longer an everyday costume. Civilians wore what James Verinis dubbed the "town foustantela" [astiki enthimasia fóustanela] only on special occasions. On the Aegean Islands, where it had never been part of peasant dress, the foustanela appeared even more ceremonial. At the turn of the century, Harriet Boyd Hawes, a British archaeologist in Crete, reported that Locals had seen the foustanela "if at all, only in patriotic plays representing heroes of the Revolution of '21." Hawes also found that when she dressed her Greek assistant in one, he could overawe Local villagers who mistook it for a government uniform."

- ^ a b Papaloizos, Theodore C. (2009). Modern Greek: Nea ellenika. Papaloizos Pub: Greek123. p. 107. ISBN 978-0-932416-02-5.

- ^ Karalis, Vrasidas (2012). History of Greek Cinema. A&C Black. p. 23. ISBN 9781441194473.

- ^ Psaras, Marios (2016). The Queer Greek Weird Wave: Ethics, Politics and the Crisis of Meaning. Springer. p. 105. ISBN 9783319403106.

- ^ Skafidas 2009, pp. 150–151.

- ^ Smithsonian Institution & Mouseio Benakē 1959, p. 31; Fox 1977, p. 56.

- ^ Smithsonian Institution & Mouseio Benakē 1959, p. 8: "The yileki (bolero), the mendani (waistcoat) and the fermeli (sleeveless coat) which are worn with the fustanella, and their mode of decoration, are reminiscent of the ornamented breastplates of ancient times. The selachi (leather belt) with its gold or silver embroidery, worn round the waist over the fustanella, and in whose pouches the armed chieftains, the Armatoli and Klephts of the War of Independence placed their arms, recalls the ancient girdle; 'gird thyself' meant 'arm thyself' (Homer, Iliad)."

- ^ Gjergji 2000, p. 182.

- ^ a b Romagnoli 2010, p. 68.

- ^ Romagnoli 2010, p. 69.

- ^ a b Trapuzzano 2005, p. 9.

- ^ Gjergji 2004, p. 207

- ^ Scarce 2017, p. 164.

- ^ "Tatavla Karnavalı" (in Turkish). Tatavla. Archived from the original on 16 December 2011. Retrieved 28 December 2011.

- ^ Tracey-Miller & Strauss 2014, p. 127

- ^ Institute of Modern Greek Studies 1998.

- ^ Oxford English Dictionary; Babiniotis 1998.

- ^ Koço 2015, p. 15.

- ^ Bada 1995, p. 137.

- ^ Balta, Evangelia; Wittman, Richard (2019). "Historical comments on the Illustrations in the Harvard Fulgenzi Album of Lithographs (1836-38)". In Collaço, Gwendolyn (ed.). Prints and Impressions from Ottoman Smyrna: The Collection de Costumes Civils Et Militaires, Scènes Populaires, Et Vues de L'Asie-Mineure Album (1836-38) at Harvard University's Fine Arts Library. Memoria : fontes minores ad historiam Imperii Ottomanici pertinentes. Vol. 4. Max Weber Stiftung. p. 76.

The 1861 depiction of an Arvanite warrior by Carl Haag at the Benaki Museum in Athens is but one of the more well-known such portrayals.

- ^ Koryllos, Christos (1903). Χωρογραφία της Ελλάδος (in Greek). Εκ του Τυπογραφείου των Καταστημάτων "Ανέστη Κωνσταντινίδου". pp. 21–23.

Sources

[edit]- Angelomatis-Tsougarakis, Helen (1990). The Eve of the Greek Revival: British Travellers' Perceptions of Early Nineteenth-Century Greece. New York and Oxford: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-03482-1.

- Athanassoglou-Kallmyer, Nina (1983). "Of Suliots, Arnauts, Albanians and Eugène Delacroix". The Burlington Magazine. 125 (965): 487–490. JSTOR 881312.

- Babiniotis, George D. (1998). Λεξικό της Νέας Ελληνικής Γλώσσας (in Greek). Athens: Kentro Leksikologias. ISBN 978-960-86190-0-5.

- Bada, Konstantina (1995). "Η παράδοση στη διαδικασία της ιστορικής διαπραγμάτευσης της εθνικής και τοπικής ταυτότητας: Η περίπτωση της "φουστανέλας"". Ethnologhia (in Greek). 4. Greek Society for Ethnology: 127–150.

- Baleva, Martina (2017). "The Heroic Lens: Portrait Photography of Ottoman Insurgents in the Nineteenth-Century Balkans - Types and Uses". In Ritter, Markus; Scheiwiller, Staci G. (eds.). The Indigenous Lens?: Early Photography in the Near and Middle East. Studies in Theory and History of Photography. Vol. 8. Walter de Gruyter GmbH & Co KG. pp. 237–256. ISBN 9783110590876.

- Baleva, Martina (2021). "Geschichtete Sichtbarkeiten. Trendsetter und Kleidercodes in Porträtfotografien vom osmanischen Balkan". In Thomas Grob; Anna Hodel; Jan Miluška (eds.). Geschichtete Identitäten: (post-)imperiales Erzählen und Identitätsbildung im östlichen Europa (in German). Böhlau Verlag GmbH & Cie. KG. pp. 71–98. doi:10.7788/9783412512255. ISBN 978-3-412-51225-5.

- Brnardic, Vladimir (2004). Napoleon's Balkan Troops. Illustrated by Darko Pavlovic. Bloomsbury. ISBN 9781841767000.

- Kukudēs, Asterios I. (2003). The Vlachs: Metropolis and Diaspora. Zitros.

- Beller, Manfred; Leerssen, Joep (2007). Imagology: The Cultural Construction and Literary Representation of National Characters: A Critical Survey. Amsterdam and New York: Rodopi. ISBN 978-90-420-2317-8.

- Bialor, Perry A. (2008). "Greek Ethnic Survival Under Ottoman Domination". Research Report 09: The Limits of Integration: Ethnicity and Nationalism in Modern Europe. Amherst, MA: University of Massachusetts.

- Blumi, Isa (2004). "Undressing the Albanian: Finding Social History in Ottoman Material Cultures". In Faroqhi, Suraiya; Neumann, Christoph (eds.). Ottoman Costumes: From Textile to Identity. Istanbul: Eren. pp. 157–180. ISBN 978-975-6372-04-3.

- Chartrand, René; Courcelle, Patrice (2000). Osprey Men-at-Arms 335: Émigré & Foreign Troops in British Service (2) 1803-15. Oxford: Osprey Publishing. ISBN 1-85532-859-3.

- De Rapper, Gilles (2005). "Better than Muslims, Not as Good as Greeks: Emigration as Experienced and Imagined by the Albanian Christians of Lunxhëri". In King, Russell; Mai, Nicola; Schwandner-Sievers, Stephanie (eds.). The New Albanian Migration. Brighton-Portland: Sussex Academic. pp. 173–194.

- Ethniko Historiko Mouseio (Greece); Maria Lada-Minōtou; I. K. Mazarakēs Ainian; Diana Gangadē; Historikē kai Ethnologikē Hetaireia tēs Hellados (1993). Greek Costumes: Collection of the National Historical Museum. Athens: Historical and Ethnological Society of Greece.

- Evans, Arthur (2006) [1886]. Ancient Illyria: An Archaeological Exploration. New York and London: I.B. Tauris. ISBN 978-1-84511-167-0.

- Flaherty, Chris (2023). Turkish Army & Navy 1826-1850. Soldiershop Publishing. ISBN 9788893279505.

- Fox, Lilla Margaret (1977). Folk Costumes from Eastern Europe. London: Chatto & Windus (Random House). ISBN 0-7011-5092-0.

- Gjergji, Andromaqi (2000). "Le costume albanais dans le contexte sud-est". Studia Albanica. 33. Academy of Sciences of Albania.

- Gjergji, Andromaqi (2004). Albanian Costumes through the Centuries: Origin, Types, Evolution (in Albanian). Tirana: Mësonjëtorja. ISBN 978-99943-614-4-1.

- Gerolymatos, Andre (2003). The Balkan Wars: Conquest, Revolution, and Retribution from the Ottoman Era to the Twentieth Century and Beyond. New York: Basic Books. ISBN 978-0-465-02731-6.

- Hoti, Afrim (1989). "Enë me glazurë nga qyteti i Durrësit (shek. X-XV)/ Récipients à glaçure découverts à Durrës". Iliria. 19 (1): 213–240. doi:10.3406/iliri.1989.1519.

- Institute of Modern Greek Studies (1998). Λεξικό της Κοινής Νεοελληνικής. Thessalonica: Aristotelion Panepistimio Thessaloniki. ISBN 9789602310854.

- Karadzic, Vuk (1852). Srspski rjecnik. Bec.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Kazhdan, Alexander Petrovich, ed. (1991). The Oxford Dictionary of Byzantium. New York and Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-504652-8.

- Koço, Eno (2004). Albanian Urban Lyric Song in the 1930s. Lanham: Scarecrow Press. ISBN 978-0-8108-4890-0.

- Koço, Eno (2015). A Journey of the Vocal Iso(n). Newcastle upon Tyne: Cambridge Scholars Publishing. ISBN 978-1-4438-7578-3.

- Konitza, Faik (1957). Albania: The Rock Garden of Southeastern Europe, and other Essays. Boston, MA: Vatra.

- Langkjær, Michael Alexander (2012). "A case of misconstrued Rock Military Style: Mick Jagger and his Evzone "little girl's party frock" fustanella, Hyde Park, July 5, 1969". Endymatologika. 4: 111–119. ISSN 1108-8400.

- Maxwell, Alexander (2014). Patriots against fashion: Clothing and nationalism in Europe's age of revolutions. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 978-1-137-27713-8.

- Meço, Irma (2011). "Martin William Leake L'Albania agli occhi di un viaggiatore inglese agli albori del sec. XIX". In Giovanni Sega (ed.). Il viaggio adriatico: Aggiornamenti bibliografici sulla letteratura di viaggio in Albania e nelle terre dell'Adriatico. Maluka, University of Tirana. pp. 399–406. ISBN 978-9928-134-00-4.

- Mesi, Agron (2019). "The "Discovery" of Albanians and Their Culture from Western Europe". 20th International Conference on Social Sciences Zurich, 6-7 September 2019 (PDF). Revistia. pp. 42–58. ISBN 978-164669411-2.

- Morgan, Charles Hill (1942). Corinth: The Byzantine Pottery. Vol. 11. Cambridge, MA: Published for the American School of Classical Studies at Athens, Harvard University Press. ISBN 9780876611111. OCLC 36957616.

- Nasse, George Nicholas (1964). The Italo-Albanian Villages of Southern Italy. Washington, District of Columbia: National Academy of Sciences-National Research Council. ISBN 9780598204004.

- Notopoulos, James A. (1964). "Akritan Ikonography on Byzantine Pottery" (PDF). Hesperia. 33 (2): 108–133. ISSN 0018-098X. JSTOR 147182.

- Romagnoli, Gianfranco (2010). "Il Reggimento Real Macedone". In Gianfranco Romagnoli (ed.). Miti e Cultura Arbëreshë (PDF) (in Italian). Italy: Centro Internazionale Studi sul Mito Delegazione Siciliana.

- Scarce, Jennifer M. (2017). "Lord Byron (1788–1824) in Albanian Dress: A Sartorial Response to the Ottoman Empire". Ars Orientalis. 47: 158–77. doi:10.3998/ars.13441566.0047.007. JSTOR 45238935.

- Skafidas, Michael (2009). "Fabricating Greekness: From Fustanella to the Glossy Page". In Paulicelli, Eugenia; Clark, Hazel (eds.). The Fabric of Cultures: Fashion, Identity, and Globalization. New York and Oxford: Taylor & Francis (Routledge). pp. 145–163. ISBN 978-1-135-25356-1.

- Smithsonian Institution; Mouseio Benakē (1959). Greek Costumes and Embroideries, from the Benaki Museum, Athens: An Exhibition Presented Under the Patronage of H.M. Queen Frederika of the Hellenes. Washington, District of Columbia: Smithsonian Institution.

- Snodgrass, Mary Ellen (2014). World Clothing and Fashion: An Encyclopedia of History, Culture, and Social Influence. London and New York: Routledge. ISBN 978-1-317-45167-9.

- St. Clair, William (1972). That Greece Might Still be Free: The Philhellenes in the War of Independence. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-215194-0.

- Suparaku, Sokol (2013). Albanità in Ebollizione. Studio delle dinamiche dell'identità e delle rappresentazioni sociali degli Albanesi nella transizione tra epoca moderna e postmoderna (PhD). Università Ca' Foscari Venezia.

- Todorova, Maria N. (1984). "The Greek volunteers in the Crimean War". Balkan Studies. 25 (2): 539–563. ISSN 2241-1674.

- Tomes, Jason (2011). King Zog: Self-Made Monarch of Albania. Stroud: The History Press. ISBN 9780752470870.

- Trapuzzano, Camillo (2005). Il costume femminile di Gizzeria. Lamezia Terme: Stampa Sud.

- Verinis, James P. (May 2005). "Spiridon Loues, the Modern Foustanéla, and the Symbolic Power of Pallikariá at the 1896 Olympic Games" (PDF). Journal of Modern Greek Studies. 23 (1): 139–175. doi:10.1353/mgs.2005.0010. S2CID 146732138.[permanent dead link]

- Weller, Charles Heald (1903). "The Cave at Vari. I. Description, Account of Excavation, and History". American Journal of Archaeology. 7 (3): 263–288. doi:10.2307/496689. JSTOR 496689. S2CID 191368679.

- Welters, Lisa (1995). "Ethnicity in Greek dress". In Eicher, Joanne (ed.). Dress and ethnicity: Change across space and time. Oxford: Berg Publishers. pp. 53–77. ISBN 978-0-85496-879-4.

- Wenzel, Marian (1962). "Bosnian and Herzegovinian Tombstones–Who Made Them and Why?". Sudost-Forschungen (21): 102–143.

- Doğer, Lale (2004). "Bizans Dönemi Fantastik Kurgulu Betimleme Taşıyan Yeni bir Seramik Obje" (PDF). Sanat Tarihi Dergisi (in Turkish). 13 (2): 79–98.

- Vroom, Joanita (2014). "Human representations on Medieval Cypriot ceramics and beyond: The enigma of mysterious figures wrapped in riddles" (PDF). In Papanikola-Bakirtzi, Demetra; Coureas, Nicholas (eds.). Cypriot Medieval Ceramics: Reconsiderations and New Perspectives. A.G. Leventis Foundation. pp. 153–189. ISBN 978-9963-0-8133-2.

- Tzortzakakis, Ioannis K. (2023). Αρχαία ελληνική και ρωμαϊκή αρχιτεκτονική στονελλαδικό χώρο σε κείμενα ταξιδιωτών του 18ου αιώνα [Ancient Greek and Roman architecture on the Greek land in 18th century travellers’ texts] (Thesis) (in Greek). School of Architecture, Aristotle University of Thessaloniki.

- Tracey-Miller, Caitlin; Strauss, Mitchell D. (2014). "Fustanella". In Lynch, Annette; Strauss, Mitchell D. (eds.). Ethnic Dress in the United States: A Cultural Encyclopedia. Rowman & Littlefield. pp. 126–128. ISBN 978-0-7591-2150-8.

- Volait, Mercedes (2021). "Guise and Disguise Before and During the Tanzimat". Antique Dealing and Creative Reuse in Cairo and Damascus 1850-1890: Intercultural Engagements with Architecture and Craft in the Age of Travel and Reform. Leiden studies in Islam and society. Vol. 12. Brill. pp. 186–241. ISBN 9789004449879. ISSN 2210-8920. JSTOR 10.1163/j.ctv1v7zbh3.10.

- Wahba, Magdi (1990). "Cairo Memories". In Neil Fodor, Tony McKenna (ed.). Studies In Arab History: The Antonius Lectures 1978-1987. Springer. pp. 103–117. ISBN 9781349206575.

![An Arvanite warrior in a watercolor painting by Carl Haag, 1861.[116]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/b/b4/Haag_Carl_-_Greek_Warrior_-_Google_Art_Project.jpg/84px-Haag_Carl_-_Greek_Warrior_-_Google_Art_Project.jpg)