Advertisement

‘Political backlash’ follows effort to reform cash bail in Texas

Resume

Find out more about our series Breaking the Bond here.

When Michelle Chapa started a new job managing a cell phone store in the Heights neighborhood of Houston, she didn’t expect it to become a target.

Over the course of two and a half years, the building was robbed on multiple occasions. Security camera footage from December 2018 shows masked men rushing onto the sales floor. One carries what appears to be an assault-style rifle.

They march Chapa to the safe, load bags with cell phones and dash out the door.

“It affected how I live life every day,” says Chapa. “I have an issue going into retail stores. I don’t go to concerts. I don’t go to large venues because I never know who's going to pull out a gun.”

Chapa was scared and she wanted to know why the robberies kept happening. She found out later that at least one of the men charged with a felony for robbing her store had picked up a misdemeanor charge earlier that year.

“I was just angry at everybody,” Chapa says. “As a victim, I felt very let down.”

At around the same time, Harris County was negotiating a settlement in a sweeping class-action federal lawsuit that would put an end to cash bail for most nonviolent misdemeanors.

It meant thousands of people accused of minor offenses would no longer spend time in jail just because they couldn’t afford to pay bail.

Even though Chapa was the victim of felonies, she says she began to feel the robberies at her store were related to misdemeanor bail reform. In the years since, she’s become focused on the issue. She spends her free time digging through county arrest data, looking for examples of repeat offenders who spiral into violent crime.

“There's no punishment, which means that people are not being held accountable for the crimes that they've committed,” she says.

Advertisement

Backlash follows bail reform

Arguments like this are common around the country as local governments consider bail reforms. In 2019, New York lawmakers ended cash bail for misdemeanors and low-level felonies.

Then, the pandemic hit. Crime went up. Opponents blamed the new law, and the legislature rolled back some of its provisions.

“You get bail reform, and then you get this political backlash, and it ends up undoing it,” says Sandra Guerra Thompson, a University of Houston Law Center professor and deputy monitor overseeing the ODonnell settlement in Harris County.

Misdemeanor bail reform did not lead to a crime spree in Houston, she says.

According to the monitor’s reporting, misdemeanor cases in Harris County fell sharply — from 61,000 in 2015 to 50,000 last year. The number of people arrested for misdemeanors who had new charges filed within one year also declined.

Instead of paying cash bail, many defendants get out on a personal-recognizance bond. With a PR bond, defendants promise to show up to their next court date.

“Every year, we had thousands of people who were unable to pay bail and so they had to sit in jail. And what usually happened to those people was that in order to get home they were forced to plead guilty,” Guerra Thompson says. “The impacts are incredible.”

Advocates for crime victims

Five years after the ODonnell agreement, the war over bail reform is ongoing.

A regular segment on the Houston Fox News station highlights stories about people getting out of jail on a PR bond — and then committing new crimes.

Victim advocates like Andy Kahan call it a “get out of jail free card.”

Kahan is the public face of the national Crime Stoppers organization in Houston. He’s been a vocal supporter of efforts at the legislature to make it tougher for some people to get out of jail.

Kahan has a stack of posters in his office covered with pictures of victims. They’ve allegedly been murdered by people who got out of jail on multiple bonds, or after getting a felony PR bond.

“Rosalie Cook, right here,” says Kahan, pointing to an image of the 80-year-old grandmother in a light blue shirt. Cook was stabbed to death in 2020 in a drugstore parking lot. “That should never have happened. She paid the ultimate price for these decisions. I can go on and on and on and talk about so many of these different cases.”

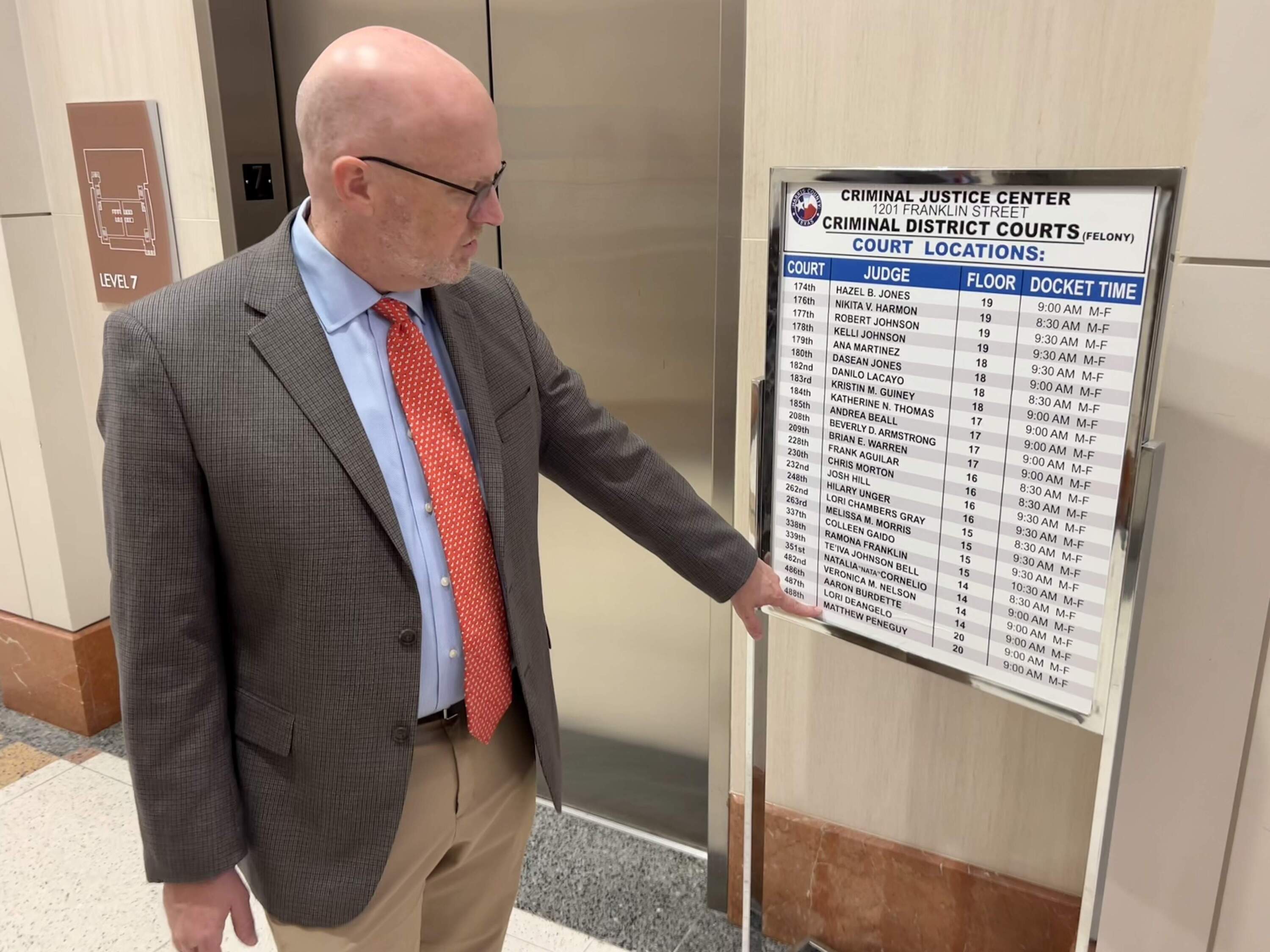

While it’s true that sometimes people do commit a serious crime while out on probation or bond, “it’s extraordinarily rare,” says Natalia Cornelio. She’s a judge of the 351st District Court in Texas, which serves all of Harris County.

Even at the worst times, more than 90% of people who are out on bail were successful, says Cornelio, a Democrat who was elected to the position.

“They show up to court. They don't get accused of violating the law,” Cornelio says. “That's how the system is supposed to work.”

But she’s also seen cases where a defendant was in jail for 1,500 days and their case was dismissed the night before trial.

“Or they were acquitted at trial,” Cornelio says. “People are actually innocent of what they're charged with sometimes and that's why we have a system that involves the presumption of innocence and the right to bail.”

Crime statistics

Violent crime has been trending downward in the United States, but that hasn’t stopped politicians from using the red-hot issue as a rallying cry this election season.

According to a recent report by the police chiefs of major cities, the number of robberies and aggravated assaults fell this year compared to last. Homicides are down 17%.

Cities like Houston, Dallas and Austin notched a similar decline. But earlier this year the Houston police chief made a surprise announcement. Since 2016, HPD stopped investigating 260,000 cases, including sex crimes and assaults. They were shelved for lack of resources.

“When the Houston Police Department does not investigate 262,000 crimes, that puts a real dent into the statistics,” says state Sen. Paul Bettencourt, a Republican who represents the Houston area.

Bettencourt is one reason why Texas has gotten tough on crime in recent years. Shortly after the settlement on misdemeanor bail in Harris County, he co-authored legislation that bans no-money PR bonds for people charged with violent felonies.

Senate Bill 6 makes “it clear that violent criminals couldn't be given bonds, especially PR bonds, like popcorn,” Bettencourt says.

Was the law a response to misdemeanor bail reform?

“Clearly for every legislative change, there's a condition in the society that generates it,” he says.

SB 6 was a big victory for advocates like Andy Kahan at Crime Stoppers, but critics say it’s added to the problem of jail overcrowding.

Meanwhile, the Republican legislature may not be done. Bettencourt says the next bail-related legislation on his radar is an effort to deny bond to immigrants who commit crimes after entering the country illegally.

That could resonate in Texas, where statewide polls show immigration and border security are top issues for voters this election. The CATO Institute, a libertarian think tank, found that undocumented immigrants in Texas were far less likely to be convicted of a crime than people born in the U.S.

Inside the Harris County courts

Some people who work in the justice system say Republicans are using bail reform to incite fear.

On any given day, crowds of lawyers, defendants and their family members move through the Harris County courthouse, a towering building in downtown Houston.

“It’s chaos,” says defense attorney Murray Newman, who sees the drama of this big-city courthouse unfold. “The reality is that there will never be a budget big enough that makes us resolve all of the issues it faces to everyone's satisfaction.”

However, Newman says misdemeanor bail reform has made the system more fair. Before the ODonnell settlement, clients who couldn’t afford bail would often plead guilty to crimes they didn’t commit just to get out of jail.

“Lawyers hate that scenario,” he says. “But it’s one we were in. There were plenty of times when we’d say, ‘Don’t take that plea bargain because you shouldn’t have to.’”

Newman says the ODonnell settlement did not lead to a spike in crime, and any suggestion that it did is fear mongering.

Conservatives at the statehouse would get rid of misdemeanor bail reforms if they could “in a heartbeat,” Newman says. “They treat it like Satan's Bible for what’s caused all the downfall. It’s just scapegoating.”

This reporting was supported by the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation.

This segment aired on September 18, 2024.