Prepositions in Discourse

Prepositions in Discourse

Uploaded by

Clarissa AyresCopyright:

Available Formats

Prepositions in Discourse

Prepositions in Discourse

Uploaded by

Clarissa AyresCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Copyright:

Available Formats

Prepositions in Discourse

Prepositions in Discourse

Uploaded by

Clarissa AyresCopyright:

Available Formats

John Benjamins Publishing Company

This is a contribution from Functions of Languages 15:2

2008. John Benjamins Publishing Company

This electronic file may not be altered in any way.

The author(s) of this article is/are permitted to use this PDF file to generate printed copies to

be used by way of offprints, for their personal use only.

Permission is granted by the publishers to post this file on a closed server which is accessible

to members (students and staff) only of the authors/s institute.

For any other use of this material prior written permission should be obtained from the

publishers or through the Copyright Clearance Center (for USA: www.copyright.com).

Please contact [email protected] or consult our website: www.benjamins.com

Tables of Contents, abstracts and guidelines are available at www.benjamins.com

English prepositions in Functional

Discourse Grammar

Evelien Keizer

University of Amsterdam

Adpositions have always been problematic in terms of analysis and representation: should they be regarded as lexical elements, with an argument structure,

or as semantically empty grammatical elements, i.e. as operators or functions?

Or could it be that some adpositions are lexical and others grammatical, or even

that one and the same adposition can be either, dependent on its use in a particular context? In Functional Grammar (Dik 1997a,b) adpositions are analysed

as grammatical elements, represented as functions expressing relations between

terms (referring expressions). Various alternative treatments have been proposed

within FG, all of which, however, fail to solve all the problems, or address all the

relevant questions involved. This article offers an analysis of English prepositions

within the model of Functional Discourse Grammar (Hengeveld and Mackenzie

2006, 2008), based on the semantic, syntactic and morphological evidence available and fully exploiting the novel features of this model.

1. Introduction1

Most linguistic frameworks (formal or functional, formalistic or non-formalistic)

acknowledge the importance of differentiating between lexical (or content) elements and grammatical (or form) elements. Functional Grammar (Dik 1997a,b)

forms no exception, and distinguishes between the two classes of elements in underlying representation: whereas the former are analysed as predicates, the latter

are analysed as operators or functions (e.g. Dik 1997:159). Such an approach is unproblematic for those elements that are clearly lexical or grammatical. Thus, whatever their background, linguists seem to agree that full verbs, nouns and adjectives

are prototypical lexical elements, whereas affixes, auxiliaries and particles are generally regarded as grammatical elements. There are, however also elements in

some cases, classes of elements whose status as lexical or grammatical is less

straightforward. One of the most problematic classes of elements in this respect

Functions of Language 15:2 (2008), 216256. doi 10.1075/fol.15.2.03kei

issn 0929998X / e-issn 15699765 John Benjamins Publishing Company

English prepositions in Functional Discourse Grammar 217

is that of adpositions, which have been classified as either lexical or grammatical

(depending on the linguistic framework in question), and sometimes as both (with

some adpositions being classified as lexical and others as grammatical).

In all standard works on the theory on Functional Grammar (Dik 1978, 1989,

1997a,b) adpositional phrases are analysed as terms with a semantic function.

This corresponds to the view taken in most grammaticalisation studies, where adpositions are typically regarded as part of the grammatical inventory (e.g. Bybee

2003:145; Heine and Kuteva 2002a:34; Hopper and Traugott 1993:4). Such an

approach deviates from the position taken in both formal and cognitive semantics,

as well as in many more syntactically oriented frameworks, where adpositions are

often assumed to form a lexical category (alongside V, N and A). Unfortunately,

the classification of adpositions as either lexical or grammatical is rarely justified

by linguistic evidence (in the form of tests or a list of criteria) (see Keizer, 2007).

The controversial nature of adpositions is also evident from the fact that, in

the course of time, various alternative treatments of adpositions have been proposed within Functional Grammar. As will be demonstrated, however, these earlier proposals fail to solve, or often even address, the basic problems involved. The

aim of the present article is to propose an analysis and representation of English

prepositions and prepositional constructions within the newly developed theory

of Functional Discourse Grammar (Hengeveld and Mackenzie 2006, 2008) which

provides answers to the following questions:2

1. Is it plausible to assume that all prepositions in English are grammatical elements and that the wide range of meanings they express are represented in

underlying structure by a very limited number of highly abstract semantic

functions?

2. If, on the other hand, we choose to analyse prepositions as predicates, should

this be true of all prepositions, or is there evidence to suggest some prepositions are better regarded as more lexical and others as more grammatical (e.g.

Lehmann 2002:1,8)?

3. Is it justified and/or feasible to distinguish between lexical and grammatical

uses of one and the same preposition (e.g. on in the book on the table vs. his

dependence on his wife)?

4. What kind of evidence can be used to determine whether prepositions are

lexical or grammatical?

The article is organised as follows. Section2 presents an overview of the various

treatments of adpositions proposed in Functional Grammar so far. In Section3

the arguments and evidence provided in these earlier proposals are evaluated

and further evidence is brought in from semantics and cognition, morphology

and syntax. Together, this information forms the basis for a new proposal for the

2008. John Benjamins Publishing Company

All rights reserved

218 Evelien Keizer

treatment of English prepositions and prepositional constructions within Functional Discourse Grammar, made in Section4. Section5 offers some conclusions.

Finally, as it will be assumed that the answers to the questions addressed may differ

from language to language, this article will be concerned with English data only.

2. Adpositions in FG: An overview

In standard Functional Grammar (henceforth FG), adpositions, as grammatical

elements, are represented as semantic functions assigned to terms (i.e. referring

expressions); the expression the mouse under the table in (1a), for instance, is given

the representation in (1a), (cf. Dik 1997a:206207):

(1) a. the mouse under the table

a. (d1x1: mouseN: {(d1x2: tableN)Loc})

In (1a), under the table is represented as a term with the semantic function

Loc(ation); within the expression the mouse under the table, this locative term is

used in an attributive function, as the second restrictor on the term variable x1

(representing the referent of the entire term).3

This approach, however, turned out to be problematic in a number of respects.

The first problem concerns the idea that adpositional phrases are represented as

terms: whereas terms are defined as referring expressions, adpositional phrases

typically fulfil a non-referring (modifying or predicative) function (as is clear from

the representation in (1a), where the curly brackets indicate a predicative function). To account for the predicative function of terms with such semantic functions as location, direction, path and source, Dik (e.g. 1997a:206207) introduces

a term-predicate formation rule, converting such terms into one-place predicates.4

This does not, however, solve the problem: the input is still a term referring to

an entity. Take an example like the mouse under the table. The modifying phrase

under the table is represented as a term, the table, with the semantic function Location. However, the table referred to is not itself the location of the mouse; instead

the term the table refers to an entity in relation to which the location of the mouse

is indicated. Nor would such a view be logically acceptable: in a sentence like The

mouse under the table looked frightened, reference is made to a mouse and a table;

the place, or location, on the other hand, is not referred to.5 Instead the property of

being under the table is predicated of the mouse, a point which was convincingly

made by Jackendoff (1983:161163), and which, within FG, has resulted in the

introduction of the p-variable (Mackenzie 1992a; now the l-variable, Hengeveld

and Mackenzie 2006, 2008).

2008. John Benjamins Publishing Company

All rights reserved

English prepositions in Functional Discourse Grammar 219

Secondly, if adpositions are to be regarded as grammatical elements, this

means that they cannot have a meaning of their own: inserted by means of an expression rule, they can only derive their meaning from the semantic function assigned to the term as a whole. The number of semantic functions available is, however, limited. As a result, such an approach cannot do justice to (a) the differences

in meaning between different adpositions expressing the same semantic function

(e.g. at, in, by, above, below, beside, opposite, across, between, before, behind, beyond

and around, all of which express Location); (b) the large range of senses of one

single adposition (e.g. the many senses of over described in various studies from

cognitive grammar, such as Brugman 1988; Brugman and Lakoff 1988, Dewell

1994; Kreitzer 1997; Tyler and Evans 2001; see also evidence from psycholinguistic

research on the functional elements determining the use of spatial prepositions,

e.g. Coventry et al. 1994, Garrod et al. 1999, Coventry 2003).

Various attempts have been made to come up with a more satisfactory treatment of adpositions and adpositional phrases in FG. Thus it has been suggested

that, to tackle the problem of underspecification, more semantic functions need to

be distinguished to match the large number of adpositions. De Groot (1989:13),

for instance, introduces the semantic function Subessive to trigger the preposition

under. As pointed out by Mackenzie (1992b:4), however, this would lead to a proliferation of semantic functions, without, however adding to the explanatory value

of the theory (see also Samuelsdorff 1998:273).

For most authors challenging the standard FG view of adpositions, however,

the crux of the matter lies in the assumption that all adpositions are grammatical elements. Weigand (1990), for instance, proposes to represent prepositional

phrases through a combination of semantic functions (e.g. Loc, Path) and a limited number of prepositional predicates (e.g. on and under). A simplified example

is given in (2):

(2) a. The mouse ran from under the table.

a. e run (ag m mouse) ([path, from] p under (y table)))

where the preposition under is analysed as a one-place predicate heading a locative

expression p,6 which in turn is used as the argument with the semantic function

Path (expressed as from). The advantage of this approach is that we need only a

small set of semantic functions, as it is not necessary to have a separate semantic

function for each locative or directional preposition.

Taking the idea of lexical prepositions one step further, Mackenzie (1992b,

2001) proposes to represent most prepositions as predicates. In addition, Mackenzie distinguishes a small set of grammatical (spatial and temporal) prepositions, which he regards as direct realisations of the semantic functions Loc(ation),

So(urce), Path, All(ative) and App(roach):7

2008. John Benjamins Publishing Company

All rights reserved

220 Evelien Keizer

(3)

Loc:

So:

Path:

All:

App:

at (spatial and temporal)

from (spatial and temporal)

via (spatial), for (temporal)

to (spatial and temporal), until/till (temporal)

towards (spatial)

All other prepositions are assumed to be stored in the lexicon as one-place predicates. These lexical prepositions can then combine with one of the five semantic

functions to form a complex preposition (e.g. in + All = into). In addition, Mackenzies proposal can accommodate such embedded prepositional constructions as

in (4a) by analysing from as the direct realisation of the semantic function Source,

which is assigned to a place-denoting term headed by the prepositional predicate

under:

(4) a. from under the table

a. (d1pi: underP (d1xi: fj: tableN)Ref )So

Moreover, Mackenzie argues, such a system can account for the use of locative adverbs (as in I met him outside), as well as for the fact that some, but not all prepositions (i.e. only the lexical ones) allow adverbial modification (e.g. right behind the

door).8

Another interesting contribution to the debate is that by Bakker and Siewierska (2002), who advocate the view that, since the distinction between lexical and

grammatical elements (of any kind) is graded rather than strict, both ought to be

included in the lexicon. This means that all adpositions, whether predicates or

grammatical elements, will be assumed to have an entry in the lexicon, which will

include either a meaning definition (in the case of lexical adpositions) or an abstract predicate (in the case of a grammatical adposition). Thus, following Mackenzie (1992b), they consider above to be a lexical preposition, with a complex set

of semantic features, procuring it a full blown entry in the lexicon (Bakker and

Siewierska 2002:160). The meaning postulate for above will therefore consist of a

number of abstract locational predicates, as represented in (6a). The lexical entry

for the grammatical preposition at, on the other hand, will contain only the abstract predicate LOC, corresponding to the semantic function LOC. Whether or

not an adposition will appear as a predicate in the underlying representation of an

expression will therefore depend on the complexity of its lexical entry.

(6) a. LEX.ENTRY= above, [P], ((xi)ZERO (xj)REF, , [SUPERIOR (xi)ZERO

(xj)GOAL: (VERTICAL)DIR & NOT (CONTACT (xi)ZERO (xj)GOAL)]

b. LEX.ENTRY= at, [P], ((xi)ZERO (xj)REF, , [LOC (xi)ZERO (xj)REF]

Prez Quintero (2004) differs from all these proposals in that she regards all adpositions as lexical items, to be represented as one-place predicates. Her reasons for

2008. John Benjamins Publishing Company

All rights reserved

English prepositions in Functional Discourse Grammar 221

rejecting the standard approach are the same as those given by Mackenzie (1992b,

2001, 2002): firstly, even if it were possible in every utterance to trigger the correct

adposition by extending the set of semantic function, such an approach would

have very little explanatory value; secondly, since adpositions can be said to have

ascriptive value in the sense that they designate a relation between two entities,

and since, according to Mackenzie (2002:3), availability for the communicative

subact of ascription is the defining property of a predicate, adpositions qualify

for predicate status (Prez Quintero 2004:158). Prez Quintero sees no reason,

however, to distinguish a set of grammatical adpositions: the fact that some adpositions have a primitive meaning, she argues, does not necessarily mean that they

cannot function as predicates (Prez Quintero 2004:159). Prez Quintero does,

however, allow for a grammatical use of certain adpositions. In that case, the adposition performs a purely syntactic function that of indicating case and has no

independent meaning. In English only three prepositions can be used this way: to,

when used to express the semantic function of Recipient; by when used to express

the semantic function of Agent; and of in such constructions as a man of honour

(Prez Quintero 2004:163164).

Most of the arguments put forward in these proposals are semantic in nature

(primitive meaning, independent meaning). Sometimes syntactic criteria have

been used (combinatory properties, predicative use, modifiability), while some arguments are of a more general theoretical nature (lack of explanatory value). With

the notable exception of Mackenzie (1992b), however, no attempt has been made

to identify a set of criteria for systematically testing the lexical-grammatical status

of adpositions. The next section will be a first step in that direction.

3. The evidence

3.1 Grammatical vs. lexical adpositions

3.1.1 Semantics and cognition

One of the central questions in determining the lexical-grammatical status of adpositions is that of whether or not adpositions some or all can be said to

have lexical content. In an approach in which all adpositions are treated as grammatical items, the answer is clearly no. All of the alternative proposals mentioned,

however, argue in favour of a system in which there are grammatical as well as

lexical adpositions.9 Such a view does, of course, beg the question of which adpositions have meaning and which do not. Unfortunately, the various proposals,

even within FG, offer different classifications. As we have seen, Weigand (1990)

recognises only a limited number of lexical predicates (including on and under),

2008. John Benjamins Publishing Company

All rights reserved

222 Evelien Keizer

whereas Mackenzie classifies almost all English prepositions as lexical, reserving

grammatical status for a small set only (at, from, to, towards, via, for and until/till).

In other frameworks, we find other classifications. In Role and Reference Grammar (RRG; Van Valin and LaPolla 1997, based on Jolly 1993), be-at and be-via are

regarded as primitives; all other prepositions are predicative and are analysed in

terms of these primitives (e.g. from = BECOME NOT be-at). Dowty (1979), on the

other hand, qualifies be-at, be-in and be-on as primitives. Clearly, there is no consensus on which (kinds of) criteria are to be used to distinguish the two classes.

Nor is it just a problem of which adpositions belong to which class; matters

are further complicated by the fact that it is difficult, if at all possible, to determine

where one category ends and the other begins. As is well-known from grammaticalisation studies, grammatical elements typically develop out of lexical elements,

whereby the exact point of transition from one category to the other is difficult,

perhaps even impossible, to establish.10 This means that even within a particular

category of words, such as adpositions, some elements will be more lexical than

others, and that, even if we are able to provide a satisfactory classification of the

clearest cases, there may always be cases that defy straightforward categorisation.

Let us, however, for the purposes of this article, concentrate on the semantic evidence available for considering adpositions (some or all) as either grammatical or lexical. As pointed out before, the standard approach of analysing all

adpositions as semantically empty elements, expressing a limited number of semantic functions, is untenable because it leads to gross underspecification. This

underspecification is due to the fact that the different prepositions have different

meanings: in English, for instance, on, under, near and in do not merely indicate

location; they each have their own specific meaning, which determines their appropriateness in a particular context. Now it may be that, generally speaking, these

meanings are more abstract and schematic than those of most nouns or verbs; this

does not, however, mean that they lack semantic content. It might, for instance, be

argued that the primary meaning of a preposition like in (say, containment), is, in

fact, much more specific than the meaning of a noun like thing or a verb like do;

similarly, the meaning of under, even in its metaphorical use, seems to be more

tangible than that of a highly abstract noun like sort. In both cases, it can be argued

that the preposition makes a greater semantic contribution to the construction

they appear in than the particular noun or verb (cf. Langacker 1987:1819).11

If there is one preposition that is generally claimed to have little semantic content, it is the preposition of (e.g. Huddleston and Pullum 2002:658; Lindstromberg

1998:195; see also Prez Quintero 2004:164), partly because, unlike the other prepositions, it no longer has any concrete, literal sense, and partly because, possibly

as a result of this, it can be used to indicate a wide range of sometimes very disparate meanings (including possession, relative-of, part-of, property-of, type-of,

2008. John Benjamins Publishing Company

All rights reserved

English prepositions in Functional Discourse Grammar 223

quantity-of, as well as age, size, form, source, content, depiction; e.g. Huddleston

and Pullum 2002:442,477). Clearly, it will be difficult to find a definition which

would capture all of these meanings. The result would obviously be a very abstract

meaning definition, like the one offered by Langacker (1992b:487; cf. 1992a:296),

according to whom [i]t seems quite accurate to describe [all these relationships]

as designating some kind of intrinsic relationship between the two participants.

Interestingly enough, however, of is typically not included in the class of grammatical prepositions. So which semantic criteria are used to decide on the lexical

or grammatical status of a preposition? Mackenzie (1992b:10) justifies the recognition of a small set of grammatical prepositions on the basis that they are primitive

elements, which defy further etymological or syntactic analysis (with reference

to Kahr 1975:43) (for syntactic evidence, see Section3.1.2). But is this really true

of each of the prepositions classified as grammatical by Mackenzie? According to

Mackenzie (1992b:16), what the five spatial prepositions at, from, to, towards and

via have in common is the property that the Ref-argument of these prepositions

is always understood as a (zero-dimensional) point in space. Now, this has indeed been acknowledged to hold for at; Herskovits (1986:128140), for instance,

describes the functions of at as locating two entities at precisely the same point in

space and construing them as geometric points (cf. Lee 2001:23). In the case of

from, via, to and towards, however, some further meaning element is clearly present, which would seem to disqualify them as primitives. To confuse matters even

more, in RRG from and to are indeed analysed as decomposable lexical elements,

whereas via is treated as a primitive (like at).

One might, however, wonder whether qualifying the referent of via and from

as zero-dimensional points in space is, in fact, justified. Although both prepositions can certainly be used in combination with non-dimensional entities, this is

by no means a requirement. Lindstromberg (1998:3940) shows that the referent

of spatial from, indicating the starting point of some path, may be precisely named

(the non-dimensional argument in (7a)), or more or less vaguely located (by means

of the one-, two- or three-dimensional arguments in (7bd), respectively).

(7) a.

b.

c.

d.

Draw a line from point A to point B.

Draw a line from somewhere on line A to line B.12

The rocker slowly rose from the surface of the moon.

The noise came from the cave.

(Lindstromberg 1998:40)

Note also that neither the Oxford English Dictionary (OED) nor the Merriam-Webster Online Dictionary (Webster) restricts the meaning of from to non-dimensional

arguments only. OED describes the relevant meaning of from simply as indicating

the place, quarter, etc. whence something comes or is brought or fetched, while

2008. John Benjamins Publishing Company

All rights reserved

224 Evelien Keizer

Webster describes from as indicating the starting point of a physical movement.

The same can be said of the preposition via. Both dictionaries describe its meaning as by way of ; OED adds to this by the route which passes through or over

(a specified place). Once again this explains why, like from, via allows for a threedimensional argument. Lindstromberg (1998:128129) even regards this as the

central meaning of via:

via is vague about the exact relationship of the path in relation to the Landmark

[here: argument; MEK]. Thus, via can be used when the path goes through the

Landmark (which is probably the central meaning), or when the path only grazes

the Landmark, or even when the path goes near but does not touch the Landmark.

Of the five spatial prepositions, this leaves us with at as the last surviving serious

candidate for primitive (and as such grammatical) status. Unlike the other four

prepositions, the primary meaning of at does seem to be location at some nondimensional point in space. By not indicating the exact relationship between the

two entities, at is indeed less specific than, for instance, in (which indicates that

the argument is a container) or on (which indicates contact with a surface). Thus,

to say of a person that he or she is in the church is more specific than to say he or

she is at the church, which may also mean in the churchyard. The question is, however, whether this makes at less meaningful, less of a content word, than in or on.

Note also that it is not merely that at is more neutral or less specific in one or more

respects than other locational prepositions. In addition, the requirement that the

argument be conceptualised as a point in space places certain restrictions on its

use, making it more specific in this respect. Consider the following examples:

(8) a. John is at the supermarket.

b. John is in the supermarket.

As pointed out before, example (8a) does not actually require John to be inside the

building, thus making its use less specific than (8b). At the same time, however, the

requirement that the argument be conceived of as a point in space causes (8a) to

be appropriate only when the speaker is at some distance from the supermarket

which, as a result, loses its dimensions whereas (8b) is more likely to be uttered

when the speaker is standing just outside (or even inside) the supermarket (Lee

2001:23). The difference between the two prepositions is therefore not simply that

the one is more abstract than the other, but that they have different meanings.13 As

such, it is doubtful whether it is justified to analyse one of them as a lexical and the

other as a grammatical element.

Finally, note that an analysis of at as the direct expression of the semantic

function Loc suggests that at functions as a superordinate to all other locational

2008. John Benjamins Publishing Company

All rights reserved

English prepositions in Functional Discourse Grammar 225

prepositions, in the sense that it expresses an abstract feature shared by all other,

more specific, locational prepositions. In that case, it should, of course, be possible

to replace any of these more specific locational prepositions by at, thereby simply

making the expression less informative. This prediction is, of course, not correct,

precisely because at has a specific meaning of its own, at least one crucial feature of

which (geometric point in space) is not shared by other locational prepositions.

In sum, it looks as though there is no semantic justification for classifying the

five spatial prepositions at, from, via, to and towards as grammatical elements:

semantically they have little in common (apart from being locational, they each

have their own specific meaning); as such, there is nothing to set them apart, as a

group, from other prepositions.

3.1.2 Syntax

One of the most widely used arguments for regarding adpositions as a grammatical

category is that they form a closed class (e.g. Samuelsdorff 1998). In many cases,

however, this statement is weakened to allow for occasional additions. Thus Huddleston and Pullum (2002:603) describe prepositions as a relatively closed class,

while in Yule (1996:76), too, we read that prepositions form a closed class because

we almost never add new prepositions to the language. According to Langacker

(1987:19), on the other hand, such additions are in fact far from exceptional, and

the class of adpositions is, in fact, essentially open-ended.14

More convincing evidence for classifying adpositions, or at least some adpositions, as grammatical elements may be provided by their behaviour with regard to

modification. The underlying assumption is, of course, that grammatical elements,

lacking lexical content, cannot be modified (e.g. Bybee et al. 1994:7). However, at

least some adpositions, so it seems, do allow for (adverbial) modification. According to Halliday (1985:188189), for instance, some English prepositions can form

groups by modification, as in right behind (the door), not without (some misgivings)

and all along (the beach). Mackenzie (1992b) uses similar examples to support his

proposal for distinguishing two classes of prepositions: a small set of grammatical prepositions, which do not allow for adverbial modification, and a larger class

of lexical prepositions, which do. Thus, an expression like right behind the door

would be analysed as in (9), where the adverb right functions as a restrictor on

the prepositional predicate (and its argument), indicating that the spatial relation

holds with more than normal geometrical precision (Mackenzie 1992b:12):

(9) a. right behind the door

a. (f1: behindP (d1x1: f2: door)Ref : f3: rightAdv)

Mackenzie subsequently argues that his proposal correctly leads one to expect that

right cannot be combined with any of the five grammatical prepositions. Admittedly,

2008. John Benjamins Publishing Company

All rights reserved

226 Evelien Keizer

it is possible to say He came right from London, but in that case, the adverb right

should not, according to Mackenzie, be analysed as modifying the from-relation,

but rather as a modifier indicating manner (modifying not the preposition, but the

verbal predicate). In other words, in example (10a) right is analysed as a restrictor

on behind me, while in (10b) it modifies the verbal predicate come:

(10) a. They came from right behind me.

b. They came right from behind me.

Note, however, that in (10b) the adverb right is analysed as a restrictor not just on

the preposition, but on the preposition together with its argument, an interpretation which I think is correct (in most cases at least). This means that the restrictor has, in fact, an entire PP in its scope, and that the expression right behind the

door had perhaps better be represented as in (11) (notice the extra pair of brackets

around behind the door):15

(11) ((f1: behindP (d1x1: f2: door)Ref ): (f3: rightAdv))

If this is, indeed, the correct analysis of constructions of this kind, the presence of

an adverb tells us nothing about the status of the preposition; even if the preposition is believed to have a grammatical function, the PP is a lexical expression and

can, as such, be modified. This may then also account for the fact that right (or

similar adverbs) can, in fact, combine with such prepositions as at, towards and

via as well. Consider, for instance, the following examples, where just and utterly

occur in non-verbal predications headed by at:

(12) a. If you go up that road its just at the bottom of that <ICE-GB:S1A-071

#53:1:D>16

b. Im not utterly at the bottom of the road <ICE-GB:S1A-020 #281:1:B>

Now, it might be argued that the adverbs in these examples function as modifiers

of the entire predication rather than the PP; although the difference in interpretation may be negligible, what would be modified would be the assignment of the

property rather than the property itself. In other cases, however, such an explanation is less plausible. Consider in this respect the sentences in (13), where by far

the most likely interpretation is that in which the adverbs right and only function

to specify more precisely the locations at the back and at Tokyo University.

(13) a. Youll find Miss Jardine right at the back there <ICE-GB:W2F-011 #11>

b. Thank you for your letter proposing a branch of Dillons dealing with

customers orders only at or for Tokyo University. <ICE-GB:W1B-019

#15:2>

Similar examples can be found for the preposition toward, as shown in (14).

2008. John Benjamins Publishing Company

All rights reserved

English prepositions in Functional Discourse Grammar 227

(14) Their planned escape was cut short when they discovered that the only way

back was the roadway the vehicle had come from straight toward the

buildings and the mysterious alien ship, still performing its excavation.

Another type of syntactic evidence that can be used to distinguish between lexical and grammatical prepositions is that of mutual exclusivity: as pointed out by

Bybee et al. (1994:7), for instance, grammatical elements cannot co-occur with

members of the same class. This is indeed one of the criteria used by Mackenzie

to justify the distinction of a separate class of grammatical preposition. Thus, sequences of prepositions like from under or to behind are analysed as combinations

of a lexical preposition (under/behind) and a grammatical preposition (from/to)

(Mackenzie 1992b:11). For the sequence from under the table to behind the door

Mackenzie therefore proposes the following underlying representation:

(15) a. from under the table to behind the door

a. (d1p1: f1: underP (d1x1: f2: tableN)Ref )So (d1p2: f3: behindP (d1x2: f4:

doorN)Ref )All

The analysis in (15b) leads us to expect that from can combine freely with all lexical prepositions, but not with any of the other grammatical prepositions. This prediction does indeed seem to be borne out, since the sequences from at, from via,

from to and from towards seem to be impossible.

Nevertheless, there are weaknesses in this line of argumentation. First of all,

the analysis proposed would lead us to expect all grammatical prepositions to

occur in similar combinations; as Mackenzie himself admits, however, such sequences as in (15a) are basically limited to from (and occasionally to) + preposition. Similarly, not all lexical prepositions can co-occur with from either. Taken

together, these facts may lead one to suspect that there may be other reasons why

only certain combinations are allowed semantic reasons, for instance. One of

these reasons may very well be that (spatial) from requires a locative argument

(denoting typically, though not necessarily, a zero-dimensional point in space).

This would explain the absence of the sequences from via, from towards and from

to (where the second prepositions are analysed as grammatical elements indicating Path, Allative and Approach), as well as such sequences as *?from up, *?from

down, *?from across (where the second prepositions would be lexical prepositions

denoting Path).17 Given the kind of relations designated by the two prepositions, it

is difficult to find a plausible interpretation for these sequences.

This leaves us with the combination from at. The first question to be answered

is whether this combination is indeed entirely unacceptable. A quick Google

search shows that this seems not to be the case (although judgements may differ);

some of the attested examples are given in (16).18

2008. John Benjamins Publishing Company

All rights reserved

228 Evelien Keizer

(16) a. Removing page headers from at the bottom and top of the page while

printing the page.

(www.mail-archive.com/[email protected]/msg04647.html)

b. Make a right turn from at the United Way sign into the parking lot.

(www.californiateenhealth.org/events_060104.asp)

c. The Boat Crew Seamanship Manual can be downloaded from at the

Office of Auxiliary website (click on Publications). (www.cgaux.org/

cgauxweb/public/tbaskaux.shtml)

Nevertheless, it is undeniably true that the combination from at is relatively rare,

and that in many cases the presence of at may even seem superfluous. The same

seems to be true for certain other combinations of from with a locative preposition (from in, from on). So why is it that some combinations of prepositions are

frequently used and perfectly acceptable, while others are rarely used and at best

questionable? A number of factors may play a role here.19 One of these concerns

the availability of a default interpretation in the given context of the PP introduced by the second preposition. Consider the contrast between ??from on the

table, which is questionable (or at least exceptional), and from under the table,

which is perfectly ok. One way to account for this difference is to assume that with

an argument like table the on-relation is the default interpretation (the surface of

the table being its most prominent feature). In other words, the expression from

the table will be interpreted as meaning from on the table; as such, use of on would

be redundant. The same would apply to the combination from in: from the building will be interpreted as from in(side) the building; from his chair as from in

his chair. Any other relation, however, must be coded explicitly (e.g. from behind,

under, nearby the building/chair). The same explanation can be given for the rare

occurrence of the combination from at: a PP like from the station, for instance, will

always be interpreted as either from at the station or from in(side) the station.

A second, related, factor that seems to play a role here is that of locational opposition: the possibility of expressing a second preposition following from seems

to be determined by the availability of (inherent) contrast with some other locational preposition (or, perhaps more generally, some other locational concept).

Thus, the acceptability of from under the table can be accounted for by the presence

of the opposition on-under; the same can be said for such combinations of from

below, from behind, from inside etc. Note that this factor interacts with the availability of a default reading: where, given the nature of the object(s) referred to, one

of the two prepositions denotes the default relation, it is the non-default preposition that is more likely to be expressed (under rather than on, behind rather than in

front of etc.). Naturally, these default prepositions can also be explicitly expressed,

in which case not surprisingly a fuller, more emphatic, form of the preposi-

2008. John Benjamins Publishing Company

All rights reserved

English prepositions in Functional Discourse Grammar 229

tion tends to be preferred (hence from inside the building, rather than from in the

building; from on top of the table rather than from on the table).20

This second factor, too, helps to explain why the combination from at is rarely

used, as at does not have a locational counterpart: the opposite of at seems to be

not-at. Finally, such an account explains why from can quite easily be followed by

at in those cases where at (or the PP introduced by at) is modified, as the presence

of a modifier adds some the inherent opposition at lacks (hence from straight at

home, from almost at the middle).

So let us continue by considering such expressions combining the presence of

a modifier with that of a second preposition. By analysing the modifiers as having

scope over the PPs as a whole, and/or by analysing all prepositions as predicates,

we can also account for the following examples, where the grammatical spatial

prepositions distinguished by Mackenzie co-occur with both a modifier and another preposition:

(17) a. Subject: HOW TO MAKE MONEY FROM RIGHT AT HOME

(THOUSANDS) (http://vishnu.mth.uct.ac.za/omei/gr/BBS/Template/

messages/msgs31703.html)

b. Work a long-bladed knife into the sidewall, then saw a zig-zag, wavy, or

more detailed pattern, cut from almost at the center hole to right where

the tire begins to curve towards the sidewall. (www.suite101.com/print_

article.cfm/75/78343)

(18) a. Mostly, its light exiting the crown at oblique angles, as when the stone is

tipped appreciably away from straight toward the viewer. (www.ganoksin.

com/orchid/archive/200206/msg00067.htm)

b. But I hadnt prepared myself for an x-ray picture, showing heavy

calcium deposit from almost to the wrist to near my elbow. (www.

chesapeakestyle.com/celebrate/mar04.html)

In (17) the preposition at occurs in combination with the preposition from. In between the two prepositions we find an adverb, which can only be taken to modify

either the following PP or, if we assume at, from, via, to and toward(s) to be lexical

elements, just the second preposition. The examples in (18) show that this is also

is true for the prepositions to and towards.

A last source of syntactic evidence to be considered here is the predicative use

of locative adverbs, some examples of which are given in (19).

(19) a. John is in/out.

b. All the shades were down.

c. The kitchen is below.

2008. John Benjamins Publishing Company

All rights reserved

230 Evelien Keizer

Now clearly, there is a relation between these locative adverbs and prepositions, as

in many cases we are dealing with the same lexical element. To account for this,

Mackenzie (1992b:12) introduces the following predicate formation rule, which

changes the category of the input predicate from preposition to adverb, while reducing the number of arguments from one to zero:

(20) Locative Adverb Creation

Input: P (xi)Ref (e.g. below the deck)

Output: Adv (e.g. below)

What is interesting is that not all prepositions can serve as input to this rule; more

specifically, that the grammatical prepositions distinguished by Mackenzie do not

have an adverbial use (see (21a)). If we assume that locative adverbs are indeed

created through a predicate formation rule, this can easily be accounted for: since

these prepositions are not lexical elements, they cannot serve as input to the predicate formation rule. This does not explain, however, why the rule does not apply to

a large majority of lexical prepositions either (on the relevant spatial reading;

example (21b)):

(21) a. * John is at/from/via/to/towards.

b. * John is under/over/above/beneath/between/against/through/beside/

among/amid/beyond.

In Section4.2, I will come back to the use of Locative Adverbs and their relation

to prepositions. I will argue that there is no need for the Locative Adverb Creation

rule, for the simple reason that we are, in fact, dealing with one and the same lexical element on both the prepositional and the adverbial use.

3.1.3 Morphology

In English, prepositions do not easily combine with other elements to form complex

elements; nor do they often form the basis of derivation or conversion processes.

Occasionally, however, they do, in which case their morphological behaviour can

be taken as an indication of their status as lexical elements.21 In this section I will

first briefly consider compounds consisting of two prepositions, as well as combinations of prepositions with elements belonging to some other lexical category;

subsequently I will consider a few cases of derivation and conversion.

Unfortunately, morphological evidence is scarce. This is partly due to the

fact that the class of prepositions is relatively small since the number of spatial

and temporal relations that require linguistic coding tends to be limited. As far

as derivation is concerned, matters are further complicated by the fact that it is

not always clear which category an element belongs to: is the over- in overact or

overhang an adverb or a preposition? And what about in and out in the expression

2008. John Benjamins Publishing Company

All rights reserved

English prepositions in Functional Discourse Grammar 231

the ins and outs? More importantly, do we really have to assume different entries

for such forms as over, in and out in the lexicon, one for the preposition and one

for the adverb?

Nevertheless, it may be useful to look at the little evidence we have. English has

a number of preposition compounds, some spelt as one word (into, onto, upon),

some as two but clearly acting as one unit (out of, up to, off to). Mackenzie (1992b)

offers a very elegant analysis of the obvious analogy in the compounds into and

onto, which is argued to result from an interaction between semantic function

(Locative vs Allative) and lexical choice (in vs on) (Mackenzie 1992b:10). The

analogy can, however, equally insightfully be accounted for if to, like in and on,

is regarded as a predicate, in which case the complex prepositions into and onto

simply result from predicate formation. This, I feel, may even be a more attractive

analysis. After all, if into is derived from a combination of a lexical locative preposition in and the semantic function All, this suggests that an extra step is required

every time before the predicate into can be retrieved from the lexicon. This would

mean that the processing of into and onto is more complex than that of compound

(lexical) prepositions (e.g. upon, nearby). A more likely explanation may be to view

into and onto as compounds of two lexical elements, stored in and retrievable from

the lexicon. The same would hold for such fixed combinations as up to, down to, off

to, on to, in from, out of, as well as for any other prepositional compounds.

Prepositions can, however, also combine with other kinds of elements. A fairly

productive combination is (or was) that of the adverbs here, there and where and a

preposition. Thus we have, for instance, thereby, therefore, thereafter, therein; hereby, hereinafter; but we also have thereto (formal, legal); hereto (formal, legal, dialectal) and whereto, as well as hitherto, and even hereat, thereat, whereat, herefrom,

therefrom and wherefrom (formal and archaic/rare). Once again there is no reason

to assume that the prepositional elements by, in and after in these compounds differ in status from at and from: the most straightforward way to deal with these cases

is to regard them all as resulting from predicate formation. The same would hold

for the combinations toward(s), inward(s), outward(s), upward(s), downward(s),

forward(s) and backward(s).

Prepositions also play a modest role in derivational processes. The most obvious examples are those where the preposition functions as a prefix. Some of these

are, in fact, quite productive, such as, for instance, over, which, can be used in

combination with nouns (overcoat, overlord), verbs (overgrow, overlook),22 adjectives (overripe, overzealous) and adverbs (overmuch). The counterpart of over, under, is similarly productive (underdog, underestimate, underhand, underwater).23

Now obviously, not all prepositions can be used as prefixes. In addition to

over and under, prepositions like out (quite productive with verbs), up (upgrade,

update), on (on-base, on-beat), off (off-beat, off-hand) and by (with nouns, e.g. by-

2008. John Benjamins Publishing Company

All rights reserved

232 Evelien Keizer

line, bypass) can be found in this function. In Present Day English we do not,

however, find at, from, via and towards as prefixes, nor for that matter most other

prepositions (such as across, between, below, beneath, against, around or among).

In OE and ME, on the other hand, some of these prepositions do occur as prefixes.

The preposition at, for instance, was a frequent prefix in OE (meaning at, close

to, to); it can also be found in some words in ME, such as at-stand(en) to stand

close to, at-rech(en) to reach to, get at, at-fore(n) before and at-hind(en) behind.

Similarly, in ME, to used to occur as a prefix in combination with verbs, nouns,

adjectives and adverbs (resulting in such forms as to-come to happen/to arrive/to

come to, to-draught, following, retinue/resort, together and to-when until what

time/how long). All these facts seem to suggest that these prepositions must be

(or must have been) lexical elements which could function as the input of some

predicate formation rule.

The same conclusion can be drawn on the basis of the few cases of conversion

involving prepositions. Thus we have the nouns up(s) and down(s) and ins and

outs, as well as the nominal forms to(s) and fro(s). It is true that in the latter cases

we are dealing with fixed expressions (Mackenzie 1992b:12), but at some point

they must have been formed on the basis of the lexical elements in and out, and to

and from.

Finally, it is possible, though rare, for a preposition to function as the root of a

derivation. Examples are the adverb inly (inwardly, internally/intimately, closely,

fully) as well as the fairly recent (specialised) derived noun aboutness.

3.2 Grammatical vs. lexical use of adpositions

So far, we have been looking at arguments and evidence presented by linguists to

show that all or some adpositions should be seen as grammatical or lexical. There

is, however, another way of looking at the lexical/grammatical distinction, whereby this distinction applies to the use of adpositions rather than the adpositions

themselves. Thus in various theoretical frameworks it is assumed that modifying

PPs are introduced by lexical adpositions, whereas complements (of verbs, nouns

or adjectives) are introduced by grammatical adpositions (in this context also referred to as functional prepositions). Consider the examples in (22).

(22) a. the book on the table

b. Johns reliance on his own ingenuity

In (22a) the PP on the table functions as a modifier of the non-relational nominal

head table; in this construction the preposition on, indicating a spatial relation,

is often assumed to be a lexical preposition with its own argument structure. In

(22b), on the other hand, the PP on his own ingenuity is generally taken to be

2008. John Benjamins Publishing Company

All rights reserved

English prepositions in Functional Discourse Grammar 233

the complement of the relational (deverbal) head reliance; in this construction

the preposition on does not indicate location and is typically analysed as a purely

grammatical element, without argument structure. This is the position taken in

recent work within generative grammar (see Corver and Van Riemsdijk 2001).

A similar approach can be found in RRG, where a distinction is made between

predicative and non-predicative uses of adpositions:

Adpositions in the periphery of the clause are always predicative, while non-predicative adpositions normally mark oblique core arguments. A given adposition

may function either predicatively or non-predicatively, depending upon which

verb it appears with; for example, from is non-predicative when it occurs with a

verb like take, which licences a source argument, as in Sally took the book from the

boy, whereas it is predicative with a verb like die, as in She died from malaria. (Van

Valin and LaPolla 1997:52)

One important implication of such an approach is that not only does the lexical/

grammatical distinction not necessarily apply to an entire syntactic category (say

adpositions), neither does it apply to specific members of a category (say, the preposition on) in all their occurrences; instead, the status of the adposition depends

on the function of the PP it introduces (modifier or complement).

The distinction between modifiers and complements is, however, notoriously

difficult to make. This is particularly true for modifier and complement PPs within

the noun phrase, which appear in the same form and position. Various attempts

have been made to draw up lists of defining features, semantic and syntactic, to

distinguish between the two types of PP. The syntactic criteria suggested include

restrictions on the number of complements (but not modifiers), coordination

(possible between PPs with the same function, but not between complements and

modifiers), use of the pronoun one (combinable with modifiers but not with complements), and differences with regard to mobility within the clause (see e.g. Huddleston 1984; Radford 1988; Huddleston and Pullum 2002). As shown in Keizer

(2004, 2007), however, what are often given as rules are at best tendencies, and as

such make very unreliable tests.

Nor is it altogether clear to what extent the prepositions introducing complements and modifiers differ semantically. One of the semantic tests suggested to distinguish between the two types of preposition concerns their selection. According

to Huddleston and Pullum (2002: 440), for instance, complements must be licensed by the head noun; i.e. in the case of a complement PP, the head noun determines the choice of preposition (or the limited range of permitted choices).

The default preposition is of, and this is often the only possibility, as in the King of

France. In some cases, particularly with deverbal nouns, some other preposition is

selected (as in reliance on, collaboration with).

2008. John Benjamins Publishing Company

All rights reserved

234 Evelien Keizer

Although it is certainly true that in the case of complements the choice of

preposition is generally speaking more restricted, this choice can hardly be used

as a criterion for complement status of the PP. For one thing, we have seen that one

and the same preposition can be used to introduce both complements and modifiers. We can have the king of France, where of is claimed to introduce a complement,

as well as a king of wood or a king of considerable intelligence, where it introduces

PP-modifiers; we can have the book on physics as well as the book on the table. According to Huddleston (1984:264), however, we can still tell which prepositions

are grammatical and which are lexical, since lexical prepositions have their own

(typically locative) meaning, whereas grammatical prepositions, lacking semantic content, are determined by the head noun (see also Huddleston and Pullum,

2002:653ff). Now, this might be argued to apply to a preposition like on in the book

on physics and the book on the table: clearly the meaning of on is locative in the

latter construction, but not in the former. In many cases, however, the distinction

between lexical and grammatical prepositions is not so straightforward. This is

first of all due to the fact that it is not always possible to establish the lexical meaning of a preposition. The best example is, presumably, the preposition of, which

at an early stage lost its original locative meaning (close to away/from, indicating

source) and has since developed a host of meanings, including geographical origin, possession, part-of, attribute-of, type-of, quantity-of and depiction-of (Huddleston and Pullum 2002:658; see also 477; Lindstromberg 1998:195). Thus, in its

present-day use, of does not seem to have a literal (spatial) meaning; nor is it at

all clear which of its uses is to be regarded as primary. Nevertheless, it is generally

acknowledged that of can introduce both complements and modifiers. In the examples in (23), for instance, the of-PPs are usually regarded as complements; those

in (24), on the other hand, are generally taken to function as modifiers.

(23)

a.

b.

c.

d.

e.

f.

the sister of Mary

the house of her former husband

the spire of the cathedral

a glass of water

the death of the emperor

the conquest of Persia

(24)

a.

b.

c.

d

e.

f.

the wines of France

a man of honour

a girl of a sunny disposition

a boy of sixteen

a frame of steel

a matter of no importance

2008. John Benjamins Publishing Company

All rights reserved

English prepositions in Functional Discourse Grammar 235

In (24), Huddleston and Pullum (2002:659) argue, the preposition of is not selected by the head and thus makes an independent contribution to the meaning. This

claim may be justified for example (24a), where of, indicating geographical origin,

comes closest to having its original locative meaning. It may also be justifiable in

(24b), where, as pointed out by Huddleston (1984:264), of can be paraphrased by

means of the (lexical) preposition with and alternates with without (a man of/without honour). In examples (24cf), however, it is much more difficult to maintain

that of contributes independently to the meaning of the construction. In all these

cases the lexical meaning of of seems to be much more elusive than, for instance,

its meaning in examples (23b&c), where the semantic contribution of the preposition (possession, part-of) is much more tangible.

In other cases, the claim that the prepositions used to introduce complements

lack semantic content is even more doubtful. Huddleston and Pullum (2002:661),

for instance, acknowledge that on the basis of this criterion it is not always easy to

draw the distinction between with-complements and with-modifiers. The primary

meanings of with are generally assumed to be non-specific proximity (Lindstromberg 1998:208) and accompaniment (Huddleston and Pullum 2002:661). When

used to express this meaning, with is usually taken to introduce PP-modifiers (a

house with a garden, a mother with her child). Other closely related and very common uses of with involve cooperation (my work with John; collaboration with other

countries), while, as pointed out by Lindstromberg (1998:212), with has a similar

meaning when it accompanies communication and participation words, such as

communication, discussion, consultation, conspiracy, talk, negotiation and participation. In all these cases with clearly has a meaning related to the primary sense.

As such, there seems to be no justification for classifying these uses of with as

functional. Nevertheless, the PPs they introduce are typically analysed as complements.

The opposite is also true: modifiers are not always introduced by lexical prepositions. This, we have seen, is true of the preposition of, the meaning of which

proved to be difficult to establish in the first place. Another case in point is the

preposition by. Its primary sense is a locative one, indicating proximity in the horizontal plane (Lindstromberg 1998:141; Huddleston and Pullum 2002:655), which

we do, indeed, find in PP-modifiers (example (25a)), though most uses of by when

used to introduce PP-modifiers are metaphorical (e.g. example (25b)). When used

to mark the Agent (example (25c)), by is generally regarded as functional, despite

the fact that here, too, the PP it introduces is a modifier.

(25) a. The belt smashed into the table by his side and his whole body flinched.

<ICE-GB:W2F-001 #135:1>

2008. John Benjamins Publishing Company

All rights reserved

236 Evelien Keizer

b. Douglas Hurd a quiet man by nature a diplomat by training couldnt

resist pointing out on Guy Fawkes Day that hed had enough of the

explosions of the past few days <ICE-GB:S2B-007 #16:1:C>

c. We had a lecture by that guy Rene Weis over there <ICE-GB:S1A-006

#20:1:B>

In sum, distinguishing between lexical and functional prepositions or uses of

prepositions on the basis of their (lack of) semantic content is problematic because the notion of semantic content is obviously graded. Neither will it do simply

to say that complements are introduced by functional prepositions and modifiers

by lexical prepositions, first of all because the distinction between complements

and modifiers is similarly difficult to make (none of the tests suggested in the literature turns out to be reliable; see e.g. Keizer 2004, 2007), and secondly because,

as we have seen, there is no reason to assume a one-to-one relationship between

complement/modifier status and the distinction between functional and lexical

(uses of) prepositions.

4. English prepositions in Functional Discourse Grammar

4.1 Relevant features of Functional Discourse Grammar

4.1.1 A general outline of the model

Now that we have discussed several current approaches and reviewed the evidence,

it is time to consider the possibilities offered by Functional Discourse Grammar

(henceforth FDG) for a more unified and consistent treatment of adpositions and

adpositional phrases. Before we can do so, however, a brief summary of the relevant features of the model may be required.

FDG (Hengeveld 2004, 2005; Hengeveld and Mackenzie 2006, 2008) is a functional-typological grammar model that is intended as the successor to FG (Dik

1997a,b). Although it shares many of the basic assumptions and general features

of FG, it also deviates from FG in a number of important respects. One crucial

difference concerns the fact that, unlike FG, FDG has a top-down organisation:

the starting point of analysis is the Speakers intention, which, via the ordered

operations of (pragmatic and semantic) formulation and (morphosyntactic and

phonological) encoding, is gradually prepared for articulation. The operations

of formulation and encoding are FDGs main concern; they are part of the central component of the model, the grammatical component. This grammatical

component does not, however, operate in isolation, but interacts with three further components: a conceptual component, containing information concerning

the intention of the Speaker; a contextual component, containing linguistic and

2008. John Benjamins Publishing Company

All rights reserved

English prepositions in Functional Discourse Grammar 237

non-linguistic contextual information (including shared speaker-hearer longterm knowledge); and an output component, where phonetic, graphological, or

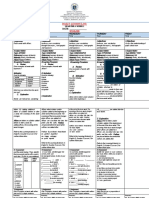

signed articulation takes place (see Fig.1).

Another feature that distinguishes FDG from FG is the internal organisation

of the grammatical component, where four modules interact to produce the appropriate linguistic forms. Each module deals with a different level of linguistic organisation. At the top of the model we find the pragmatic and semantic modules,

rendering the Interpersonal and Representational levels of analysis, respectively.

Both these levels are the output of the process of formulation. Information from

these levels then enters the phase of encoding: first that of morphosyntactic encoding, yielding a Morphosyntactic level, and finally that of phonological encoding, yielding a representation at the Phonological level.

Finally, these four levels not only receive their input from the other components and levels, but also from further information contained within the grammatical component; i.e. from the language users knowledge of his/her language.

This information, which takes the form of primitives, comes in three types. Firstly,

there is information about the patterns available in the language; at the Interpersonal and Representational levels, this information takes the form of frames (indicating acceptable valency structures), at the Morphosyntactic level of templates

(yielding the possible word order patterns), and at the phonological level of prosodic patterns. Secondly, there is information about the items available: lexemes

for formulation, auxiliaries for morphosyntactic encoding and (bound) morphemes for phonological encoding. Thirdly, each level has its own set of operators

and functions, i.e. abstract triggers of grammatical processes.

For the purposes of this article, we only need to consider two levels of analysis:

the Interpersonal level and, in particular, the Representational level. The Interpersonal level deals with all the formal aspects of a linguistic unit that reflect its role

in the interaction between Speaker and Addressee. In keeping with the overall

architecture of FDG, the units of discourse relevant at this level are hierarchically

organised. A simplified representation is given in (26):

(26) (MI: [(AI: [(FI: ILL) (PI) (PJ) (CI: [(TI) (RI) ])])])

At the highest level in this hierarchy we find the Move, which describes the entire segment of discourse relevant at this level. The Move consists of one or more

(temporally ordered) Acts (AI, AJ), which together form its (complex) Head. Each

Act in turn consists of an Illocution (FI), the Speech Participants (PI and PJ) and a

Communicated Content (CI). Finally, within the Communicated Content, one or

more Subacts of Reference (RI) and Ascription (TI) are evoked by the Speaker.

2008. John Benjamins Publishing Company

All rights reserved

238 Evelien Keizer

Conceptual component

Frames

Lexemes

Interpersonal and

representational

operators

Formulation

Interpersonal Level

Representational Level

Templates

Grammatical

morphemes

Morphosyntactic

operators

Morphosyntactic Encoding

Morphosyntactic level

Templates

Suppletive forms

Phonological

operators

c

o

n

t

e

x

t

u

a

l

c

o

m

p

o

n

e

n

t

Phonological Encoding

Phonological level

Output component

Figure1. FDG: general layout

The Representational level deals with the semantic aspects of a linguistic unit; it

is the level of denotation, where the appropriate lexemes are chosen to describe

entities in some (real or imagined) non-linguistic world. Since these entities are of

different orders, the linguistic units at this level differ with respect to the ontological category they denote. The hierarchical structure of the Representational level

is as follows:

(27) (pi: [(epi: [ (ei: [(fi)) (xi) (li) (ti) ])])])

2008. John Benjamins Publishing Company

All rights reserved

English prepositions in Functional Discourse Grammar 239

The most straightforward type of entity is the individual, a first-order entity (xi).

Entities of this type are concrete, can be seen and touched, can be located in time

and space, and can be evaluated in terms of their existence. State-of-affairs (SoAs)

are second-order entities (ei); they can be located in space and time, and evaluated in terms of their reality. Third-order entities, or propositions, are mental constructs (pi). They cannot be located in time or space; they can be evaluated in terms

of their truth. In addition to these three orders of entities (already distinguished

by Lyons 1977:442447), several more semantic categories can be distinguished.

Thus, there are separate units denoting location (li) and time (ti); since the concepts of time and space cannot be reduced to any of the other entity types, but instead rather specify dimensions of those entity types, they are seen as constituting

independent semantic categories (cf. Mackenzie 1992a for location and Olbertz

1998 for time). At the lowest level of the hierarchy, the entity denoted is a property

or relation (fi). Properties and relations do not have independent existence but can

only be evaluated in terms of their applicability. Finally, in between the proposition and the SoA we find another special semantic category, the episode (epi).

Episodes represent a combination of units of another semantic category; they may

be defined as a semantically coherent set of SoAs.

The primitives selected at the Representational level include the lexemes (predicates) used to describe the entity denoted and the appropriate frames, specifying

the number of arguments and their roles in the SoA. These roles are represented

by means of a restricted number of semantic functions (indicated by in (27), e.g.,

Actor, Undergoer, Location).

4.1.2 The representation of adpositions

At the Interpersonal level, the adpositional construction as a whole is analysed

either as a subact of reference (as in I put the book on the table, where on the

table is interpreted as referring to a place) or as a subact of ascription (when used

predicatively, as in The book is on the table). Note that by separating the referential

and ascriptive functions of adpositional phrases from their denotation, and by

analysing adpositional phrases as denoting places and times rather than objects,

one of the problems of the standard FG account has been solved: since adpositional phrases are no longer analysed as terms referring to first order entities, they

can be used either in a referential or in an ascriptive function as such the rule of

term-predicate formation is no longer required.

The crucial level of analysis for adpositions and adpositional phrases is, however, the Representational level: first, because it is at this level that a distinction

is made between different types of entity denoted (e.g., events, propositions, objects or locations); secondly, and even more importantly, because it is here that

the distinction between predicates and semantic functions is relevant. What we

2008. John Benjamins Publishing Company

All rights reserved

240 Evelien Keizer

know is that adpositional constructions are analysed as units denoting location or

time, symbolised by the variables l and t, respectively (Hengeveld and Mackenzie

2006). What still needs to be established, however, is whether to analyse adpositions (all or some) as predicates restricting these variables, as in (28a), or as semantic functions assigned to a term headed by a nominal predicate, as in (28a):24

(28) a. (1l1: atP (1l2: (stationN))Ref )

a. (1l1: stationN)Loc

In addition, we need to consider the question of which frames are needed for the

coding of adpositional constructions at the Representational level.

4.2 The proposal

4.2.1 Lexical prepositions and grammatical use

The proposal for the treatment of adpositions and adpositional phrases to follow

will start from the assumption that all English prepositions are lexical elements,

to be represented in the lexicon with a meaning definition. Such a treatment does

justice to the fact that all adpositions, in most of their uses, have some measure

of semantic content (Section3.1.1), as well as to the fact that adpositions share a

large number of syntactic and morphological properties with nouns, verbs and

adjectives (Sections3.1.2 and 3.1.3). In addition, it will be argued that a very limited number of adpositions can, in some of their uses, more plausibly be regarded

as grammatical elements, marking rather than describing the relation between a

head and some argument or modifier. In English the only prepositions to be analysed this way are of and by, and only in those cases where they are used to indicate

the semantic functions of Agent (or Positioner, Force, Processed or ) or Patient;

i.e. the semantic functions typically assigned to the first or second argument of a

verbal predicate.

This means, first of all, that adpositional phrases are analysed as expressions

with an adpositional first restrictor. Their prototypical denotation is a place, but

PPs may also denote a time or some other abstract entity. They typically function

as modifiers within a clause (e.g. I bought the book in Paris) or NP (e.g. the book

on the table). If, however, their presence is required to complete the meaning of

a verbal, nominal or adpositional first restrictor (head), they are to be analysed

as arguments (e.g. of verbal predicate like put, a nominal predicate like father, or

some other preposition, typically from).

However, before we turn to the representation of lexical adpositions, let us

first explore in some more detail the idea that some adpositions can be used grammatically, and that in English this use is limited to the prepositions of and by when

used to introduce terms with the semantic function of Agent, Positioner, Force,

2008. John Benjamins Publishing Company

All rights reserved

English prepositions in Functional Discourse Grammar 241

Processed, or Patient (i.e. the semantic functions that can be assigned to the first

and second arguments of verbal and adjectival predicates; see Dik 1997a:118).

Consider, for instance, the use of the preposition of in NPs with a deverbal nominal predicate. Some simple examples are given in (29):

(29) a. the fall of the city

b. the destruction of the city

Following Dik (1989, 1997a; see also Dik 1985a, 1985b), I will regard the nominal

predicates fall and destruction in these examples as derived from the corresponding verbal predicates to fall and to destroy, respectively, through a rule of predicate formation affecting the syntactic category and form of the derived predicate.

According to this rule, both the valency of the input predicate and the semantic

functions of the arguments are preserved in the process. The predicates fall and

destruction in (29) are formed as follows:

(30) Verbal Noun Formation:

a. Input: fallV (xi)Proc

Output: fallN (xi)Proc

b. Input: destroyV (xi)Ag (xj)Go

Output: destructionN (xi)Ag (xj)Go

However, the rule of verbal noun formation does not only affect the form of the input predicate, but also that of the arguments. This is accounted for by the Principle

of Formal Adjustment (Dik 1997b:157158):

(31) Principle of Formal Adjustment (PFA):25

Derived secondary constructions of type X are under pressure to adjust their

formal expression to the prototypical expression model of non-derived,

primary constructions of type X.

Modifiers within the term typically appear in the form of adjectives, genitives,

adpositions and relative clauses. The PFA accounts for the fact that the Agent and

Patient terms of a transitive input predicate (e.g. example (32a)) can appear as ofor by-PPs, or as genitival modifiers in the term (e.g. examples (32a-a)):

(32)

a. Caesar destroyed the city.

a. the destruction of the city by Caesar

a. Caesars destruction of the city

a. the citys destruction by Caesar

In other words, the grammatical use of adpositions is restricted to those cases where

the adposition expresses a semantic function which in the corresponding verbal

construction is not expressed by means of an adposition but by some (other) gram-

2008. John Benjamins Publishing Company

All rights reserved

242 Evelien Keizer

matical means, such as word order, agreement or case. It seems therefore reasonable

to assume that when they appear in the derived construction the prepositions of and

by do not have semantic content, but are indeed simply expressions of the semantic

relations in question. This approach is further corroborated by the fact that it is only

these semantic functions (i.e. Agent, Positioner, Force, Processed, or Patient in

FG; now Actor and Undergoer) which in the nominal domain can be expressed by

the likewise grammatical means of a genitive (e.g. examples (32a& a)).

Nor does the fact that in these cases the PPs are represented as terms form a

problem. Unlike in the case of locative PPs, the semantic functions of Agent, Patient etc. do apply to the term itself. Thus, whereas in a construction like the mouse

under the table, the term the table does not itself refer to the location, but rather as

the object in relation to which the location of the mouse is defined, in an expression