Uncle Sam

Uncle Sam (which has the same initials U.S. as United States) is a common national personification of the federal government of the United States or the country in general. Since the early 19th century, Uncle Sam has been a popular symbol of the U.S. government in American culture and a manifestation of patriotic emotion.[3] Uncle Sam has also developed notoriety for his appearance in military propaganda, popularized by a 1917 World War I recruiting poster by James Montgomery Flagg.[4]

According to legend, the character came into use during the War of 1812 and may have been named for Samuel Wilson. The actual origin is obscure.[5] The first reference to Uncle Sam in formal literature (as distinct from newspapers) was in the 1816 allegorical book The Adventures of Uncle Sam, in Search After His Lost Honor.[6]

While the figure of Uncle Sam specifically represents the government, the female figure of Columbia represents the United States as a nation. An archaic character, Brother Jonathan, was known to represent the American populace.

Earlier personifications

[edit]

The earliest known personification of the United States was as a woman named Columbia, who first appeared in 1738 (pre-US) and sometimes was associated with another female personification, Lady Liberty.

With the American Revolutionary War of 1775 came Brother Jonathan, a male personification. Brother Jonathan saw full literary development into the personification of American national character through the 1825 novel Brother Jonathan by John Neal.[7][8]

Uncle Sam finally appeared after the War of 1812.[9] Columbia appeared with either Brother Jonathan or Uncle Sam, but her use declined as a national person in favor of Liberty, and she was effectively abandoned once she became the mascot of Columbia Pictures in the 1920s.

A March 24, 1810, journal entry by Isaac Mayo (a midshipman in the US Navy) states:

weighed anchor stood down the harbor, passed Sandy Hook, where there are two light-houses, and put to sea, first and the second day out most deadly seasick, oh could I have got onshore in the hight [sic] of it, I swear that uncle Sam, as they call him, would certainly forever have lost the services of at least one sailor.[10]

Evolution

[edit]An 1810 edition of Niles' Weekly Register has a footnote defining Uncle Sam as "a cant term in the army for the United States."[11] Presumably, it came from the abbreviation of the United States of America: U.S.

Samuel Wilson legend

[edit]

The precise origin of the Uncle Sam character is unclear, but a popular legend is that the name "Uncle Sam" was derived from Samuel Wilson, a meatpacker from Troy, New York, who supplied rations for American soldiers during the War of 1812. There was a requirement at the time for contractors to stamp their name and where the rations came from onto the food they were sending. Wilson's packages were labeled "E.A.—U.S." When someone asked what that stood for, a co-worker jokingly said, "Elbert Anderson [the contractor] and Uncle Sam," referring to Wilson, though the U.S. actually stood for "United States".[12]

Doubts have been raised as to the authenticity of this story, as the claim did not appear in print until 1842.[13] Additionally, the earliest known mention definitely referring to the metaphorical Uncle Sam is from 1810, predating Wilson's contract with the government.[10]

Development of the character

[edit]

In 1835, Brother Jonathan made a reference to Uncle Sam, implying that they symbolized different things: Brother Jonathan was the country itself, while Uncle Sam was the government and its power.[14]

A clockmaker in an 1849 comedic novel explains "we call...the American public Uncle Sam, as you call the British John Bull."[15]

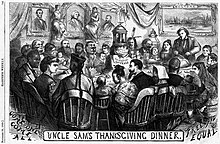

By the 1850s, the names Brother Jonathan and Uncle Sam were being used nearly interchangeably, to the point that images of what had previously been called "Brother Jonathan" were being called "Uncle Sam". Similarly, the appearance of both personifications varied wildly. For example, one depiction of Uncle Sam in 1860 showed him looking like Benjamin Franklin,[16] while a contemporaneous depiction of Brother Jonathan[17] looks more like the modern version of Uncle Sam, though without a goatee.

An 1893 article in The Lutheran Witness claims Uncle Sam was simply another name for Brother Jonathan:

When we meet him in politics we call him Uncle Sam; when we meet him in society we call him Brother Jonathan. Here of late Uncle Sam alias Brother Jonathan has been doing a powerful lot of complaining, hardly doing anything else. [sic][18]

Uncle Sam did not get a standard appearance, even with the effective abandonment of Brother Jonathan near the end of the American Civil War, until the well-known recruitment image of Uncle Sam was first created by James Montgomery Flagg during World War I. The image was inspired by a British recruitment poster showing Lord Kitchener in a similar pose.[citation needed] It is this image more than any other that has influenced the modern appearance of Uncle Sam: an elderly white man with white hair and a goatee, wearing a white top hat with white stars on a blue band, a blue tail coat, and red-and-white-striped trousers.

Flagg's depiction of Uncle Sam was shown publicly for the first time, according to some, on the cover of the magazine Leslie's Weekly on July 6, 1916, with the caption "What Are You Doing for Preparedness?"[1][20] More than four million copies of this image were printed between 1917 and 1918. Flagg's image was also used extensively during World War II, during which the US was codenamed "Samland" by the German intelligence agency Abwehr.[21] The term was central in the song "The Yankee Doodle Boy", which was featured in 1942 in the musical Yankee Doodle Dandy.

There are two memorials to Uncle Sam, both of which commemorate the life of Samuel Wilson: the Uncle Sam Memorial Statue in Arlington, Massachusetts, his birthplace; and a memorial near his long-term residence in Riverfront Park, Troy, New York. Wilson's boyhood home can still be visited in Mason, New Hampshire. Samuel Wilson died on July 31, 1854, aged 87, and is buried in Oakwood Cemetery, Troy, New York.

In 1976, Uncle Sam was depicted in "Our Nation's 200th Birthday, The Telephone's 100th Birthday" by Stanley Meltzoff for Bell System.[22]

In 1989, "Uncle Sam Day" became official. A Congressional joint resolution[23] designated September 13, 1989, as "Uncle Sam Day", the birthday of Samuel Wilson. In 2015, the family history company MyHeritage researched Uncle Sam's family tree and claims to have tracked down his living relatives.[24][25]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b "The Most Famous Poster". American Treasures of the Library of Congress. Archived from the original on July 2, 2016.

- ^ "Walter Botts, the Man Who Modeled Uncle Sam's Pose for J.M. Flagg's Famous Poster". Archived from the original on November 19, 2017. Retrieved February 21, 2018.

- ^ Terry Allan Hicks (2006). Uncle Sam. Marshall Cavendish 2006, 40 pages. p. 9. ISBN 978-0761421375. Archived from the original on August 14, 2021. Retrieved August 1, 2015.

- ^ "What's the deal with Uncle Sam?". Archived from the original on January 21, 2022. Retrieved September 27, 2020.

- ^ Schauffler, Robert Haven (1912). Flag day; its history. New York : Moffat, Yard and Co. p. 145.

- ^ pp. 40–41 of Albert Matthews, "Uncle Sam". Proceedings of the American Antiquarian Society, v.19, 1908. pp. 21–65. Google Books Archived October 3, 2015, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Morgan, Winifred (1988). An American Icon: Brother Jonathan and American Identity. Newark, New Jersey: University of Delaware Press. p. 143. ISBN 0-87413-307-6.

- ^ Kayorie, James Stephen Merritt (2019). "John Neal (1793–1876)". In Baumgartner, Jody C. (ed.). American Political Humor: Masters of Satire and Their Impact on U.S. Policy and Culture. Santa Barbara, California: ABC-CLIO. p. 88. ISBN 978-1-4408-5486-6.

- ^ "Uncle Sam". Encyclopædia Britannica Online. Archived from the original on January 20, 2013. Retrieved June 9, 2012.

- ^ a b Zimmer, Ben (July 4, 2013). "New Light on "Uncle Sam" referencing work at USS Constitution Museum in Charlestown, Mass". Archived from the original on July 3, 2015. Retrieved July 2, 2015.

- ^ Niles' Weekly Register. Vol. 7. Franklin Press, Baltimore. 1815. p. 187.

- ^ Wyandott Herald, Kansas City, August 17, 1882, p. 2

- ^ Matthews, Albert (1908). "Uncle Sam". Proceedings of the American Antiquarian Society, Volume 19. Archived from the original on October 3, 2015. Retrieved July 2, 2015.

- ^ Morgan, Winifred (1988). An American icon: Brother Jonathan and American identity. University of Delaware Press. pg. 81.

- ^ Haliburton, Thomas Chandler (1839). The Clockmaker, Or the Sayings and Doings of Sam. Slick of Slickville: To which is Added, the Bubbles of Canada, by the Same Author. Baudry. p. 20.

- ^ An appearance echoed in Harper's Weekly, June 3, 1865 "Checkmate" political cartoon (Morgan, Winifred (1988) An American icon: Brother Jonathan and American identity University of Delaware Press pg 95)

- ^ On page 32 of the January 11, 1862, edition Harper's Weekly.

- ^ December 7, 1893 "A Bit of Advice" The Lutheran Witness he pg 100

- ^ "Unknown | [Man Whittling a Stick]". The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Retrieved October 12, 2024.

- ^ "Who Created Uncle Sam?". Life's Little Mysteries. Live Science. Archived from the original on December 3, 2008. Retrieved February 16, 2012.

- ^ Macintyre, Ben. Operation Mincemeat, p. 57. ISBN 978-1-4088-0921-1

- ^ "Stanley Meltzoff Archives: The 1976 Bell System Telephone Book Cover" Archived August 13, 2021, at the Wayback Machine JKL Museum of Telephony (December 19, 2015); retrieved March 16, 2021

- ^ "Bill Summary & Status – 100th Congress (1987–1988) – H.J.RES.626 – All Congressional Actions – THOMAS". Library of Congress. Archived from the original on July 5, 2016. Retrieved September 13, 2013.

- ^ "New York Butcher is Named as Real Live Uncle Sam". The New York Times. July 3, 2015. Archived from the original on July 8, 2015. Retrieved July 3, 2015.

- ^ "The History Behind Uncle Sam's Family Tree". Fox News. July 3, 2015. Archived from the original on March 10, 2021. Retrieved July 3, 2015.

Further reading

[edit]- Bivins, Thomas H. "The body politic: the changing shape of Uncle Sam." Journalism Quarterly 64.1 (1987): 13-20.

- Dewey, Donald. The art of ill will: The story of American political cartoons (NYU Press, 2007). online

- Gerson, Thomas I. The Story of Uncle Sam: Godfather of America (March 1959) West Sand Lake, NY: "Uncle Sam" Enterprises, Inc.

- Mouraux, Cecile, and Jean-Pierre Mouraux. Who Was "Uncle Sam": Illustrated Story of the Life of Our National Symbol. Sonoma, CA: Poster Collector (2006). OCLC 70129530

- Jacques, George W. The Life and Times of Uncle Sam (2007). Troy, NY: IBT Global. ISBN 978-1933994178.

- Palczewski, Catherine H. "The male Madonna and the feminine Uncle Sam: Visual argument, icons, and ideographs in 1909 anti-woman suffrage postcards." Quarterly Journal of Speech 91.4 (2005): 365-394. online[dead link]

- Wilde, Lukas RA, and Shane Denson. "Historicizing and Theorizing Pre-Narrative Figures—Who is Uncle Sam?." Narrative 30.2 (2022): 152-168. online

- A collection of reviews of the book "Who Was Uncle Sam" by Jean-Pierre and Cecile Moreaux.

External links

[edit]- Uncle Sam: The man and the meme by Natalie Elder (National Museum of American History)

- Historical Uncle Sam pictures

- James Montgomery Flagg's 1917 "I Want You" Poster and other works at the Wayback Machine (archived October 28, 2004)

- What's the origin of Uncle Sam? The Straight Dope

- Uncle Sam online, links to 550 books

- Uncle Sam

- Culture of the United States

- Fictional American people

- Legendary American people

- National symbols of the United States

- National personifications

- Holiday characters

- Fictional characters introduced in the 19th century

- Tall tales

- American mascots

- Fictional characters based on real people

- American folklore

- American legends