Pretty much all our early discussions about graphs in RavenDB focused on how to build the actual graph implementation. How to allow fast traversal, etc. When we started looking at the actual implementation, we realized that we seriously neglected a very important piece of the puzzle, the query interface for the graphs.

This is important for several reasons. First, ergonomics matter, if we end up with a query language that is awkward, it won’t see much use and complicate the users’ lives (and our own). Second, the query language effectively dictate how the user think about the model, so making low level decisions that would have impact on how the user is actually using this feature is probably not a good idea yet. We need to start from the top, what do we give to the user, and then see how we can make that a reality.

The most common use case of graph queries is the friends of friends query. Let’s see how this query is handled in various existing implementation, shall we?

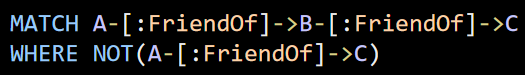

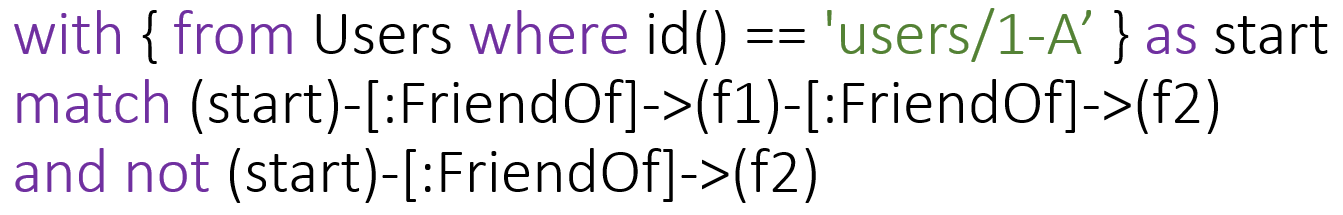

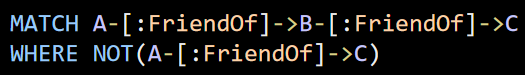

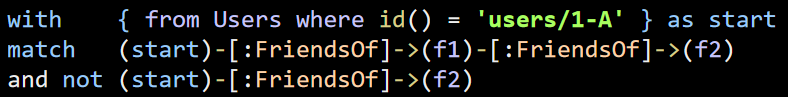

Neo4J, using Cypher:

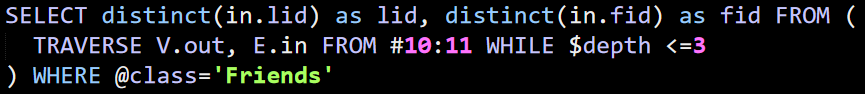

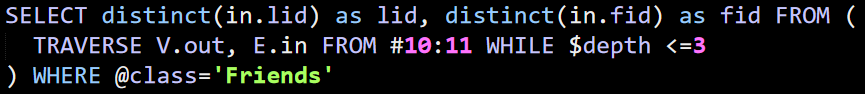

OrientDB doesn’t seem to have an easy way to do this. The following shows how you can find the 2nd degree friends, but it doesn’t exclude friends of friends who are already your friends. StackOverflow questions on that show scary amount of code, so I’m going to skip them.

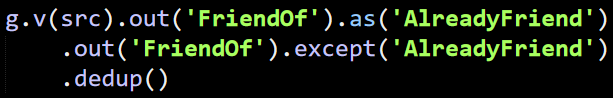

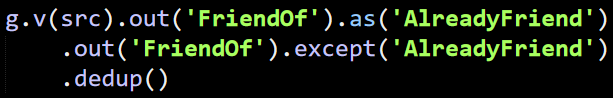

Gremlin, which is used in a wide variety of databases:

We looked at other options, but it seems that graph query languages fall into the following broad categories:

- ASCII art to express the relationship between the nodes.

- SQL extensions that express the relationships as nested queries.

- Method calls to express the traversal.

Of the three options, we found the first option, using ASCII Art / Cypher as the easier one to work with. This is true both in terms of writing the query and actually executing it.

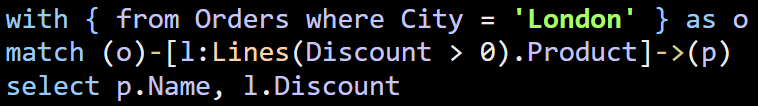

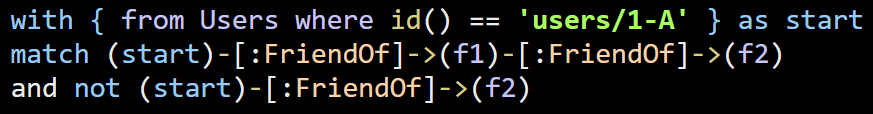

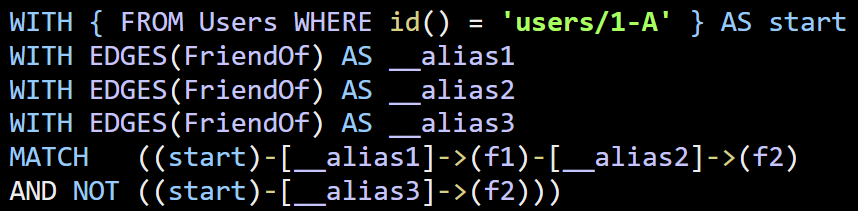

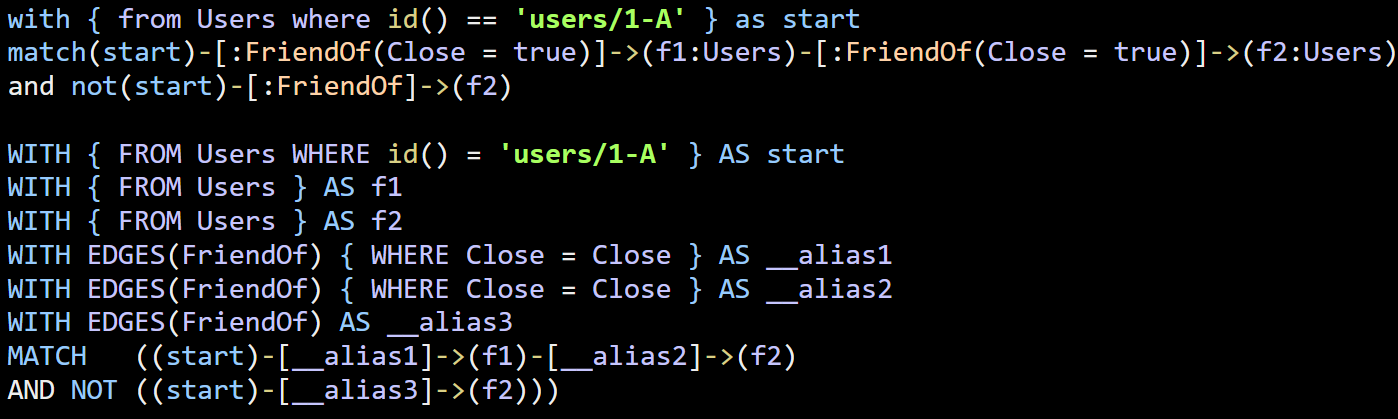

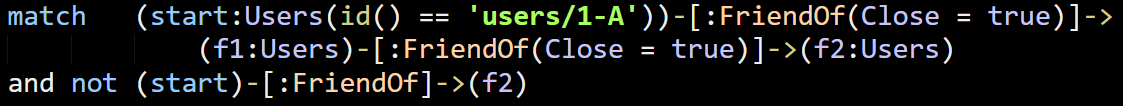

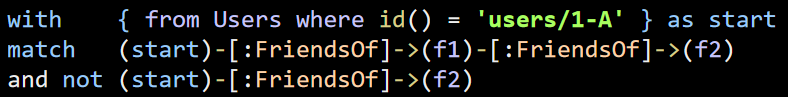

Let’s look at how friends of friends query will look like in RavenDB:

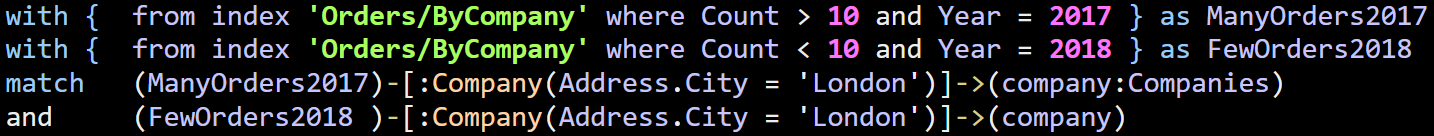

Graph queries are composed of two portions:

- With clauses, which determine source point for the graph traversal.

- Match clause (singular) that contain the graph pattern that we need to match on.

In the case, above, we are starting the graph traversal from start, this is defined as a with clause. A query can have multiple with clauses, each defining an alias that can be used in the match clause. The match clause, on the other hand, uses these aliases to decide how to process the query.

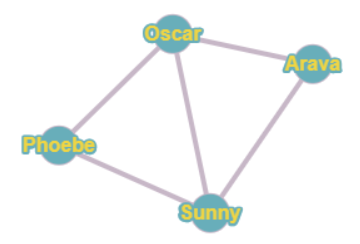

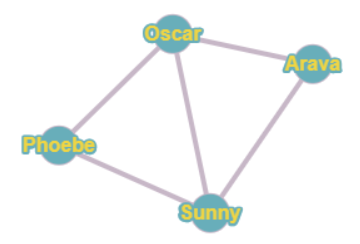

You can see that we have two clauses in the above query, and the actual processing is done by pattern matching (to me, it make sense to compare it to regular expressions or Prolog). It would probably be easier to show this with an example. Here is the relationship graphs among a few people:

We’ll set the starting point of the graph as Arava and see how this will be processed in the query.

For the first clause, we’ll have:

- start (Arava) –> f1 (Oscar) –> f2 (Phoebe)

- start (Arava) –> f1 (Oscar) –> f2 (Sunny)

- start (Arava) –> f1 (Sunny) –> f2 (Phoebe)

- start (Arava) –> f1 (Sunny) –> f2 (Oscar)

For the second clause, of the other hand, have:

- start (Arava) –> f2 (Oscar)

- start (Arava) –> f2 (Sunny)

These clauses are joined using and not operator. What this means is that we need to exclude from the first clause anything that matches on the second cluase. Match, in this case, means the same alias and value for any existing alias.

Here is what we need up with:

- start (Arava) –> f1 (Oscar) –> f2 (Phoebe)

start (Arava) –> f1 (Oscar) –> f2 (Sunny) - start (Arava) –> f1 (Sunny) –> f2 (Phoebe)

start (Arava) –> f1 (Sunny) –> f2 (Oscar)

We removed two entries, because they matched the entries from the second clause. The end result being just friends of my friends who aren’t my friends.

The idea with behind the query language is that we want to be high level and allow you to express what you want, and we’ll be in charge of actually making this work properly.

In the next post, I’ll talk a bit more about the query language, what scenarios it enables and how we are going to go about processing queries.